Tumours are more complicated than previously believed

What was once considered a fundamental principle in understanding how cancer tumours grow has been shown to be wrong.

As early as the 1800s, medical doctors have known about the importance of a blood supply in allowing cancer tumours to grow.

In the 1970s, one researcher was able to quantify this, by observing that if a tumour were going to grow larger than two or three millimetres, it would need new blood vessels.

That observation and the mechanism it describes, called angiogenesis, fed great optimism in cancer research. Enormous amounts of time and money were spent studying this idea, and new cancer medicines were developed to affect the development of blood vessels that feed tumours.

“The enthusiasm for this approach at that time was similar to how we look at immunotherapy today,” said Tom Dønnem, a professor at the Arctic University of Norway. “Now we think that immunotherapy will revolutionize cancer treatment. That’s what we once thought about angiogenesis inhibitors.”

Dønnem is the first author of a review article recently published in Nature Reviews Cancer. The article, written with colleagues from the University of Oxford and other leading researchers in the field, shows that this theory is actually partly wrong.

No benefit from treatments

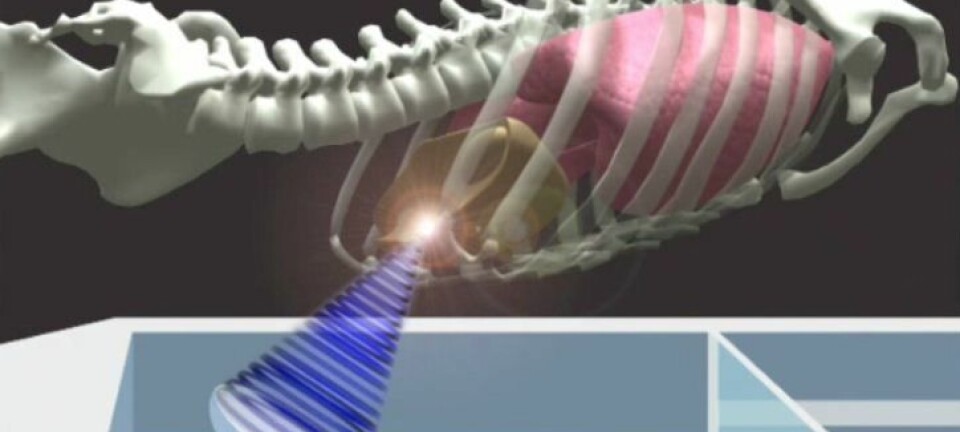

Dønnem and his colleagues have shown in the new article that solid cancer tumours also use existing blood vessels for their oxygen supply and for the substances they need to grow.

He thinks this new understanding should change treatment strategies for some cancer patients.

"Many patients who have been treated with cancer medicine that was designed to affect a tumour’s blood supply have not had any benefit from the treatment. Some patients have also experienced side effects, such as increased risk of bleeding,” he said.

Was seen as a wonder drug

The theory that a cancerous tumour has to have new blood vessels to grow is actually quite logical, says Dønnem.

Tumours must have oxygen and nutrients to grow. Dønnem himself was initially an eager supporter of this theory.

“For many types of cancer, these medicines, angiogenesis inhibitors, were seen as highly promising. The idea was that it was possible to choke the blood supply to the tumour so that it did not get the oxygen and nutrients it needed to grow,” he said.

Others believed that angiogenesis inhibitors would help improve the effectiveness of other cancer treatments, such as chemotherapy and radiation. In all of these cases, the fundamental idea was that the new blood vessels in the cancerous tumour should be the point of attack.

Sceptics in Oxford

After Dønnem took his doctorate at the University of Tromsø in 2009, he spent time as a visiting researcher at the University of Oxford. Here he worked with world-leading researchers studying tumours and the formation of new blood vessels.

By this time, researchers couldn’t figure out why treatment with angiogenesis inhibitors seemed to work for some patients but not others.

The Oxford researchers wondered if the idea of angiogenesis might be wrong. They asked if perhaps a cancerous tumour could use existing blood vessels in the body where the cancer was. In organs with many blood vessels, such as the lungs, liver, kidney and brain, this seemed to be the case.

"When one of my colleagues from Oxford presented these results at a conference, he was met with a cold shoulder from the lead author of the 1970 study on angiogenesis,” Dønnem said. “This was his life work that was being questioned.”

Eventually, after Dønnem and his colleagues began to question this idea in a series of journal articles, more and more researchers began to see that angiogenesis might not be everything it was thought to be.

But it took years.

Have lost a lot of time

Dønnem thinks it's a paradox that some established truths are so strong in medicine that they can inhibit new avenues of research for many years.

"Today scientists know that most cancer tumours use both existing and new blood vessels to grow. But in some cases, such as lung cancer, roughly 20-30 per cent of tumours grow only around the old blood vessels,” he said.

Now researchers are working to determine which tumours are affected by angiogenesis inhibitors and which are not.

However, Dønnem says, angiogenesis inhibitors do have a positive effect in some cases, especially for patients whose tumours have spread and where the treatment is designed to prolong life.

-------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no.