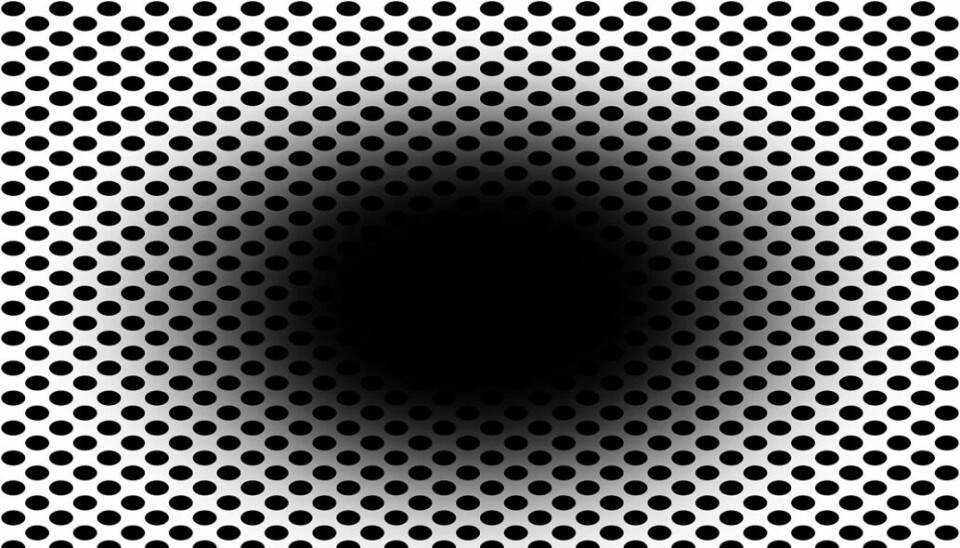

This optical illusion makes people feel like they're falling into a black hole

80 per cent of participants in a study experienced this phenomenon. Researchers believe that the illusion is a useful misinterpretation.

The black spot is actually completely stationary against the white background with black dots.

But for the majority of us, it seems to be growing.

The feeling can be described as falling into a black hole.

If you experience this optical illusion, your pupils will probably change as well. They will expand as if the black spot really is growing bigger right in front of you.

Illusions are shortcuts to understanding the brain

50 participants took part in the new study, which was conducted at the University of Oslo.

The researchers who created the optical illusion measured how the participants' eyes changed when they looked at it.

Then they asked the participants how they experienced what they saw on the screen.

80 per cent answered that the black spot grew. And the more they perceived that the spot was growing, the more the pupils expanded.

Illusions are not just fun, but shortcuts that can show how the brain works, neuroscientist Susana Martinez-Conde explained in this article on forskning.no (link in Norwegian).

The brain predicts what will happen in the future

So what happens when we think the spot is growing bigger?

The explanation is that our brain is not able to interpret what we see as fast as we might think, the researchers write in a study published in the scientific journal Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.

Therefore, the brain has to guess what will happen in the near future. According to a theory from 2008, the brain shows us a prediction of what will happen in 100 milliseconds.

According to the researchers, this is actually quite clever. Especially when either the world around us or we ourselves are in motion.

Useful when driving

Imagine driving into a dark tunnel.

In such instances it is very important that your pupils have time to expand as you enter the tunnel so that you can see in the dark. But the brain is not able to interpret the visual impressions quickly enough.

Therefore, it assumes or guesses that the black hole will continue to get bigger as you approach the entrance to the tunnel.

The brain thus shows you a useful prediction of what is going to happen.

And it is this mechanism that plays a trick on us when we look at this optical illusion.

Blurred edges play a trick on the brain

The black spot in the picture does not actually move or grow though, so what’s going on here?

It is the blurred edges of the black circle specifically that fool the brain, according to researchers.

The brain perceives this as movement outwards. Therefore, it assumes that the shape will grow.

At the same time, your pupils are dilating and getting bigger. So your brain guesses that the dark spot will soon fill a larger part of your field of vision.

But what about those who do not see the illusion?

“It is common for people to experience visual images in different ways,” psychology professor Bruno Laeng at the University of Oslo writes in an e-mail to sciencenorway.no.

He cites the viral phenomenon #thedress from 2015 as an example. An image of a dress circulated online and was perceived very differently depending on who looked at the image – either blue and black, or white and gold.

“We believe that this can be explained based on the idea that you and I can have slightly different assumptions about what we see,” Laeng writes.

In the case of the black hole, according to the professor, it is most likely that the minority does not interpret the image as a three-dimensional scene, i.e., as a hole. Instead, they experience the image two-dimensionally and therefore not something they can move into.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Reference:

Laeng et al. The Eye Pupil Adjusts to Illusorily Expanding Holes Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 2022 https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2022.877249