Banan Sultan broke the world record in memory

“Anyone with a strong desire and a goal can do what I did,” she says.

Our brain is a super machine capable of learning the most incredible things.

And with practice and repetition, you can set a world record.

“You don't have to be born with superpowers to have a good memory,” researcher Olav Schewe says. He provides some useful tips.

But first, let’s talk to Banan Sultan Nassereddine from Lebanon.

In record time

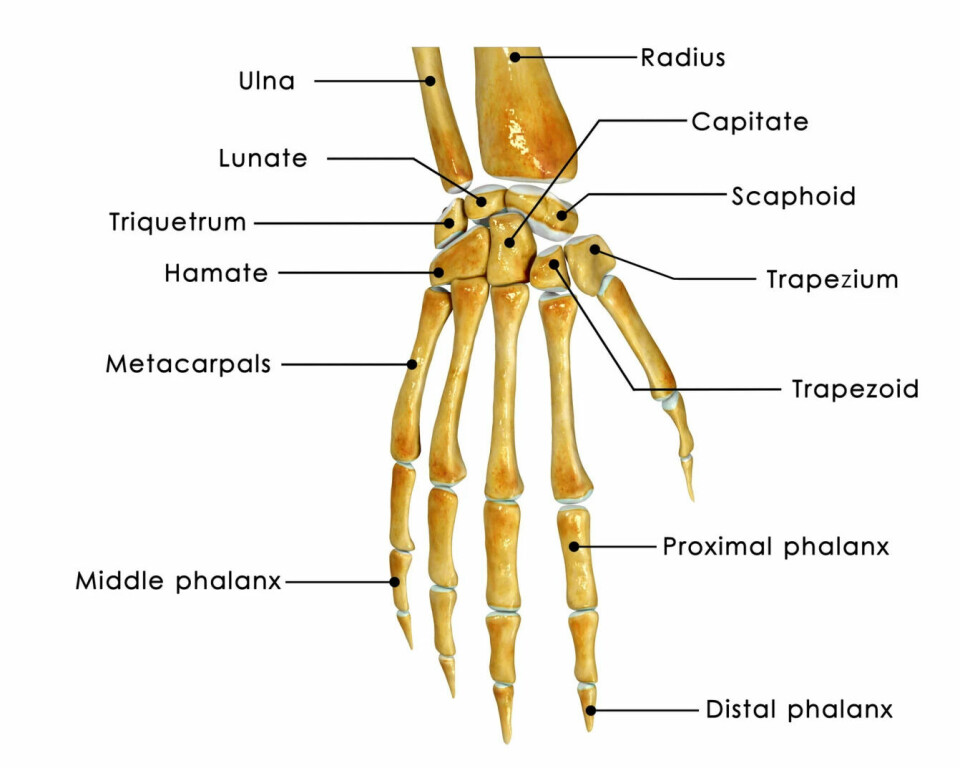

Nassereddine memorised the names of the 206 bones in the body. Then she recited them at lightning speed in front of people from the Guinness World Records.

“I did it in 5 minutes and 37 seconds,” she says.

She stood in front of a screen displaying different parts of the body.

As soon as the bones were pointed out, she recited their names.

(Video: Safir High School)

“There were two people who timed it, two biology experts, and he audience at the venue,” she says.

“How did you manage to remember all the bones?”

“I practiced over and over again. First, I divided the body into four parts and memorised one group at a time,” she says.

Not only did she have to remember the names, but she also had to distinguish between the different bones.

Without superpowers

Nassereddine says she is an ordinary teenager without superpowers.

“Anyone with a strong desire and a goal can do what I did,” she says.

She does four things that help the brain along the way. She reads, engages in physical activity, plans, and gets enough sleep.

“What will you do if someone breaks your record?”

“Then I will try to beat it again. And it might even attempt to break my own record before that,” she says.

Training the brain

Researcher Olav Schewe is impressed.

“This is inspiring for anyone who wants to memorise things,” he says.

There is a World Memory Championship to test memory skills.

“People there have managed to memorise the order of an entire deck of cards in under 20 seconds,” he says.

He agrees with Nassereddine. Practice makes perfect.

“Those who compete are ordinary people who have started training their brains,” he says.

The brain likes pictures

Schewe has conducted extensive research on how to improve our memory and has several tips.

“Our brain loves pictures. It may therefore be helpful to visualise or find pictures related to what you want to remember,” he says.

Another tip is to test yourself.

“Let’s say you want to learn the capitals of Europe. It’s better to do more than just look at a list,” he says.

Creating flashcards is a good idea. Write ‘Spain’ on one side and the capital ‘Madrid’ on the other.

“Then you can guess for yourself and flip the card. Over time, you remove the cards you know well,” Schewe says.

Make sure to shuffle the order of the cards.

Acts like the brain’s truck

Schewe suggests repeating the information over several days. The main reason is sleep.

“We have two centres in our brain called the hippocampus,” he says.

They function as intermediate storage.

“When we read a book, we store a lot of information here,” he says.

When we go to sleep, the hippocampus works like a truck.

It drives off to our long-term memory.

“There’s a vast area where the truck can unload information,” Schewe says.

When the break is over, and we continue learning, the truck drives back.

“So we need breaks for the truck to have time to unload everything,” he says.

The brain has room for all the books in the world

“Can our brains become full?”

“No. There’s plenty of space in our long-term memory,” Schewe says.

There is not enough time in a lifetime to fill it up.

“If you were to memorise all the books in the world, you would only use a small portion of your brain's long-term memory,” he says.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on ung.forskning.no