Emil Korsmo’s goal was to beat back weeds. But the wall charts he made of the bothersome plants were beautiful and popular

Weeds are no longer just plants we want to get rid of. Many people are concerned about biodiversity, while others have become increasingly captivated by harvesting wild plants to eat.

Emil Korsmo was manager for the municipality of Kristiania's properties in the late 1800s.

He was educated as an agronomist and had taken courses in botany and drawing. He began studying the kind of seeds that sprouted from manure and agricultural soil. He found not only food plants, but many wild plants.

In 1902 he was awarded support to travel around the country and study the weed flora. He discovered that some fields and meadows had so many weeds that farmers thought it was more trouble than it was worth to harvest them.

He calculated that weeds were causing farmers to lose NOK 18 million a year, or nearly NOK 1 billion in today's value.

That led him to declare war on Norway’s weeds, says Liv Borgen. She is a botanist and former professor at the University of Oslo’s Natural History Museum.

“It became a lifelong task for him, and the man lived until he was 90. He worked at it long after he retired,” she says.

Borgen has been acting section chief for the Oslo Botanical Garden, where Emil Korsmo conducted many of his experiments with weeds.

Getting to know the enemy

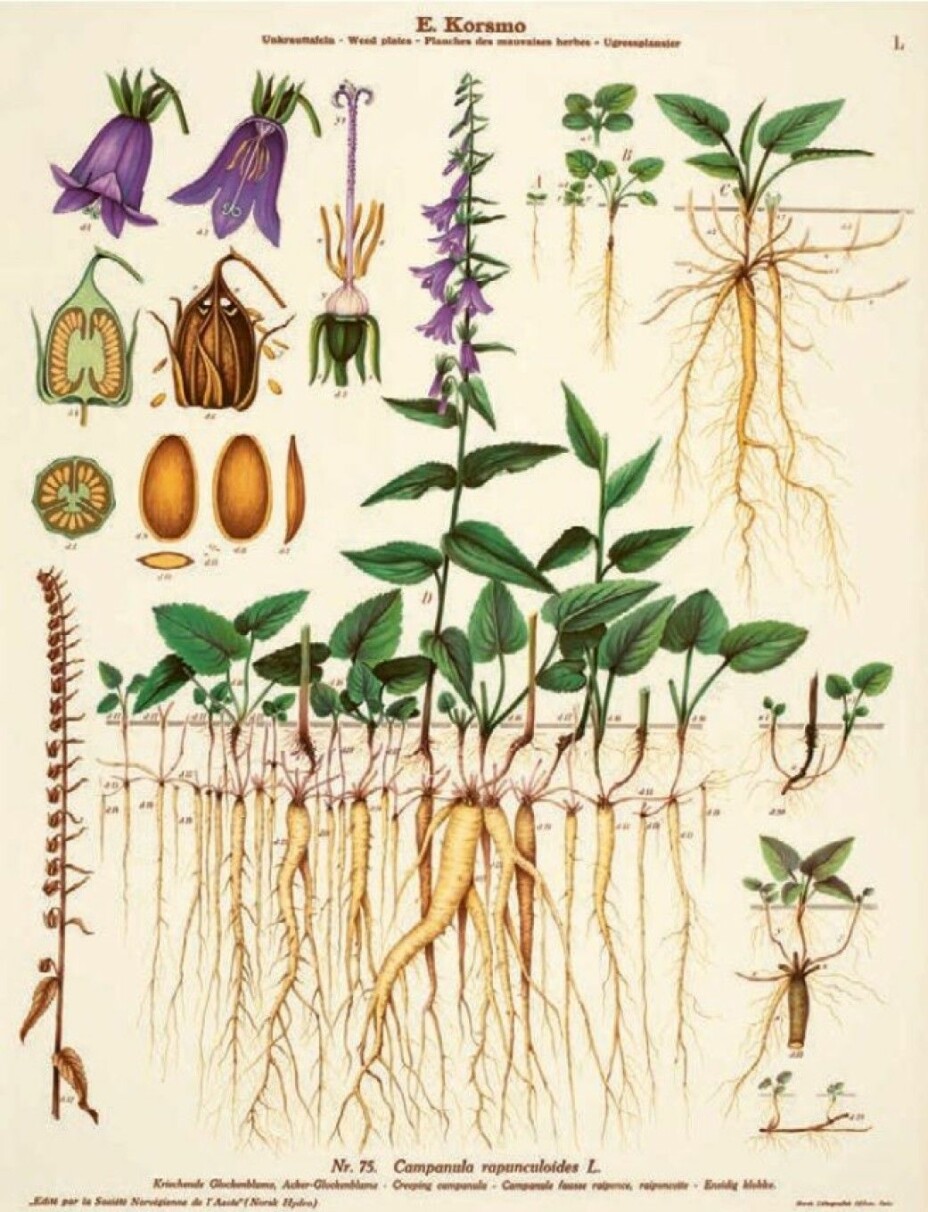

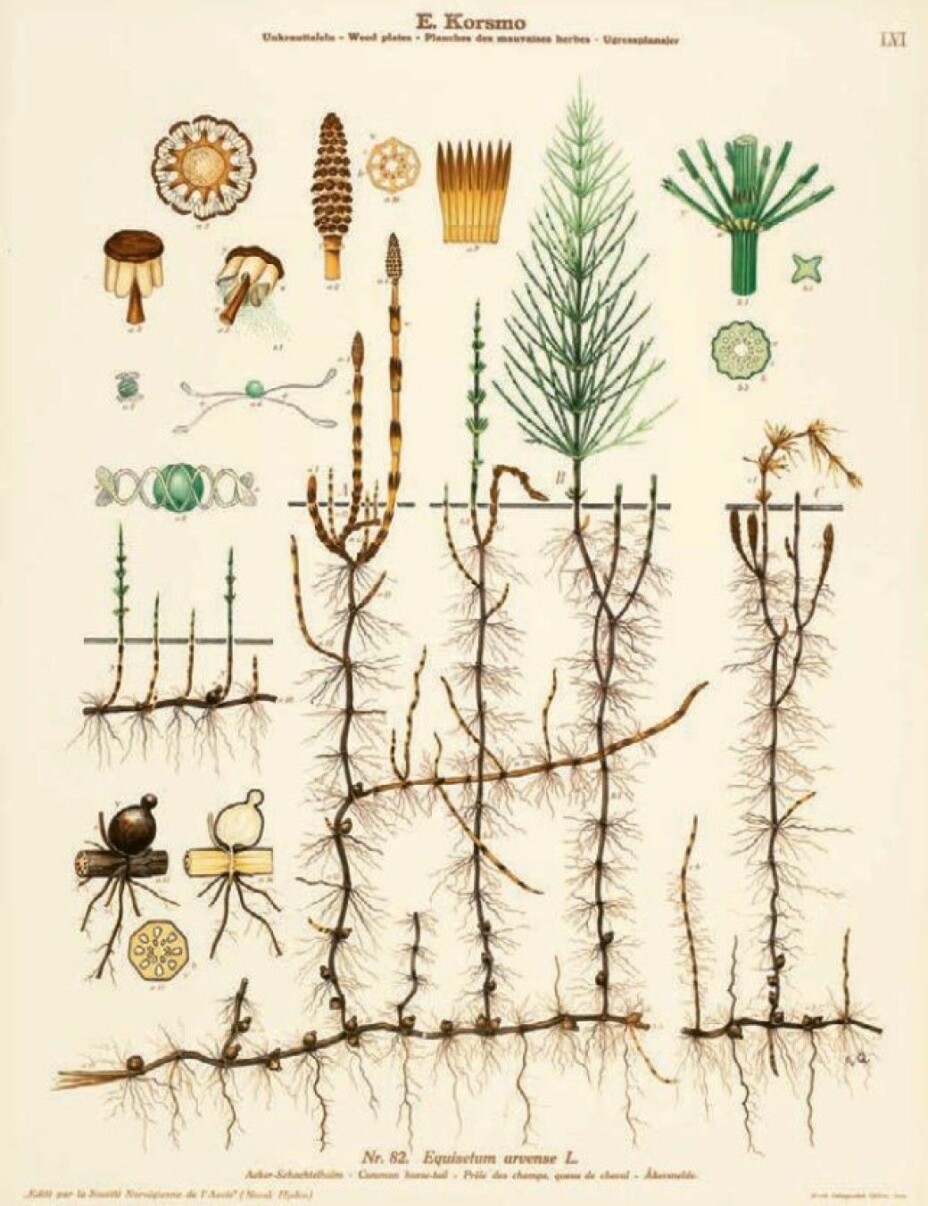

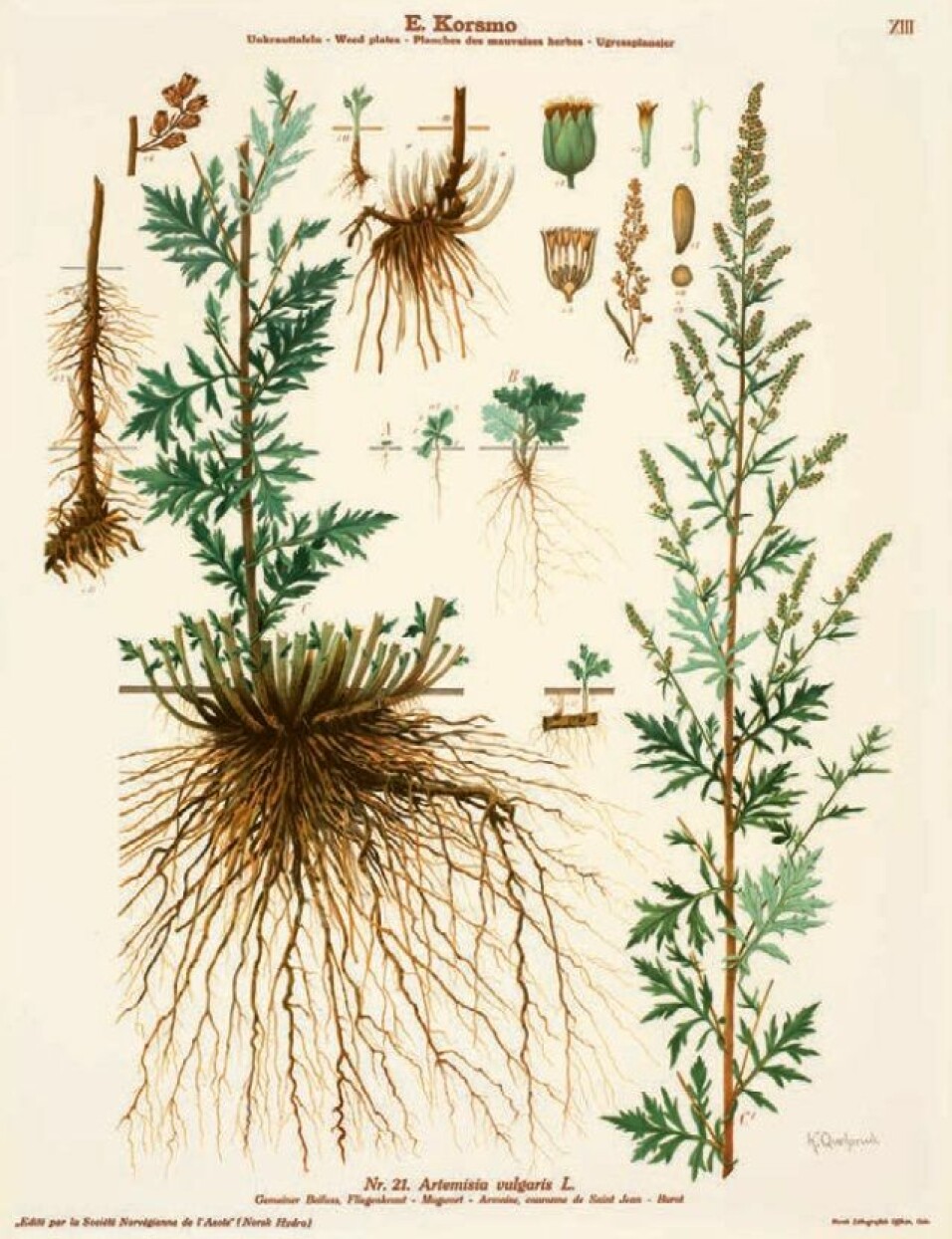

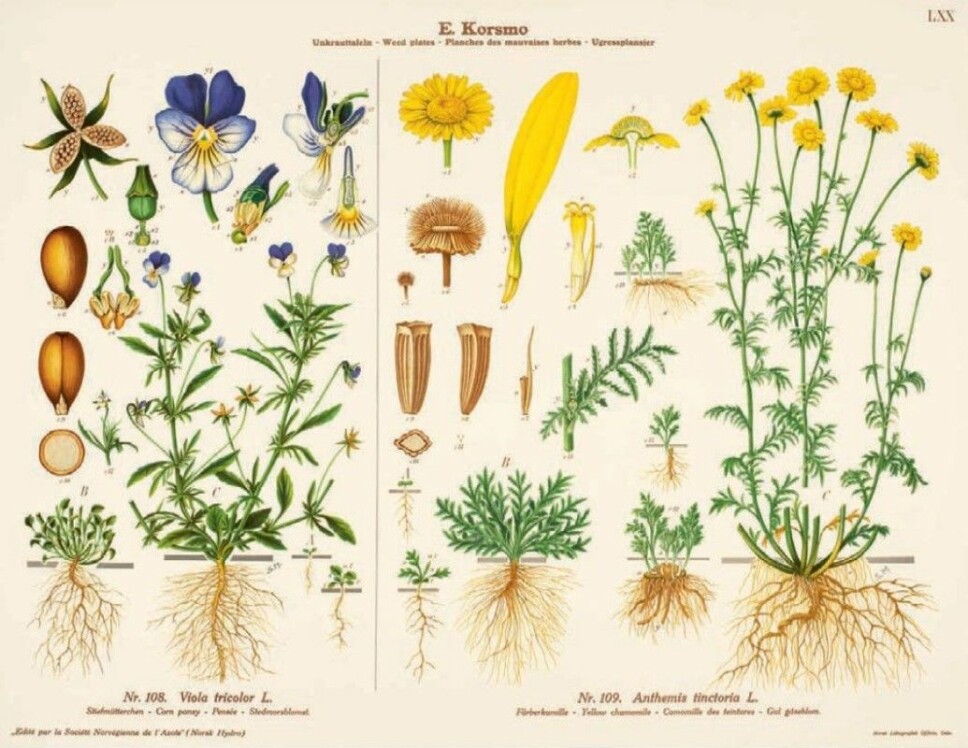

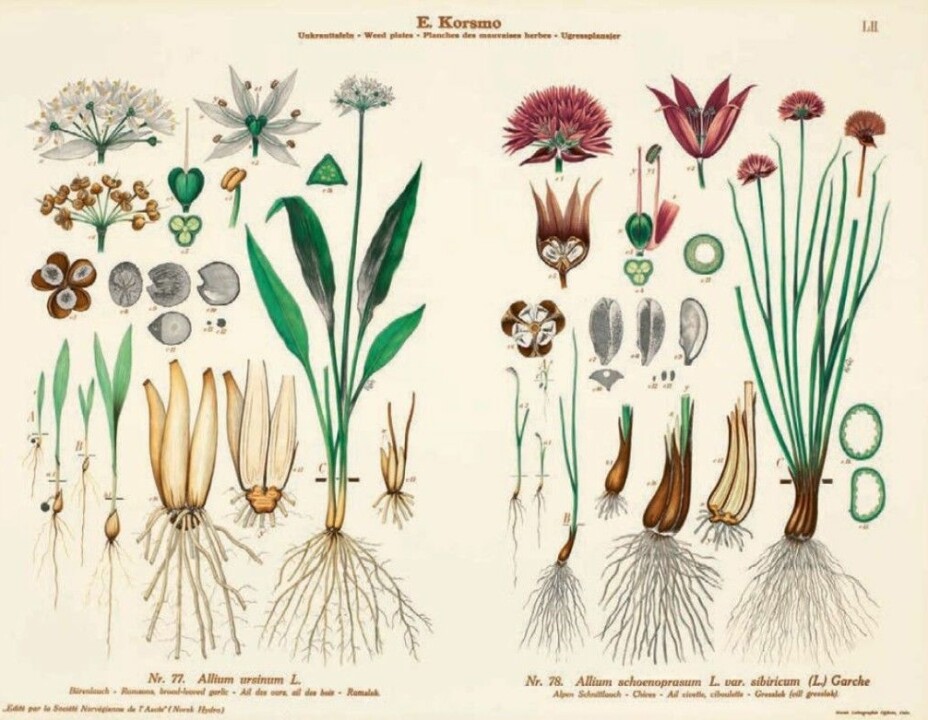

“Korsmo wanted farmers to really learn how the weeds propagated and what they looked like, both from above and below ground, and how they could be beaten back,” Borgen says.

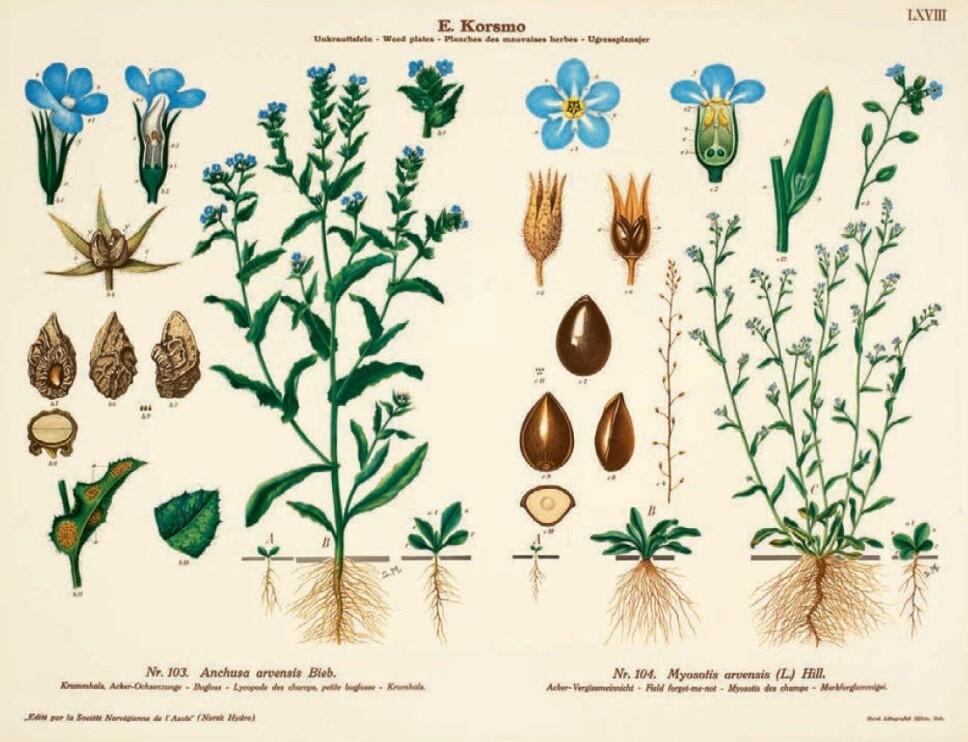

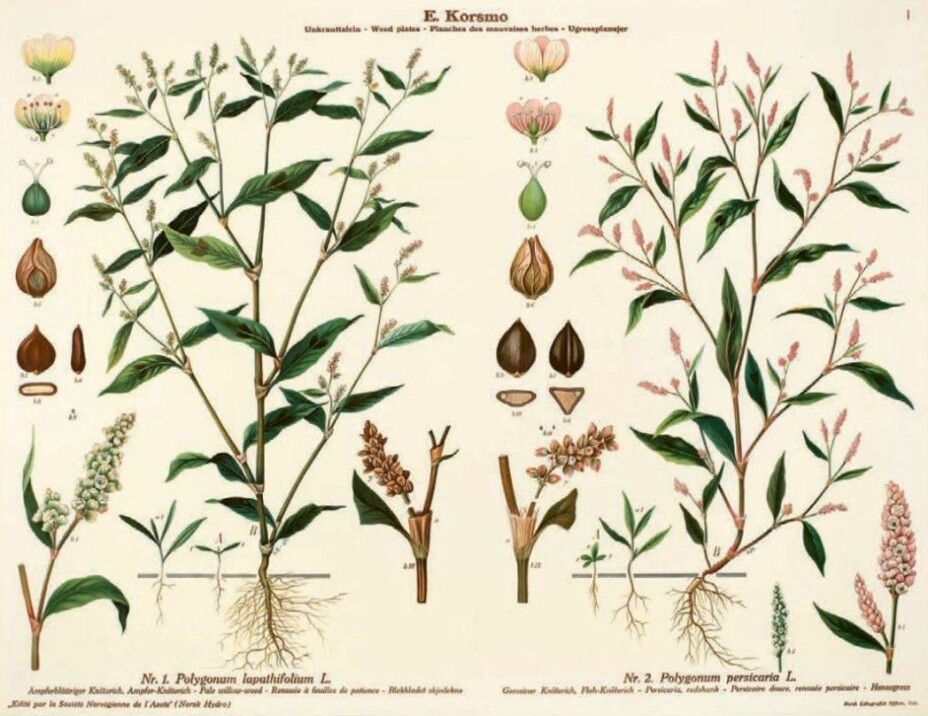

In collaboration with the illustrator Knut Torkildsen Quelprud, Korsmo published detailed weed charts of the hated plants. This is how he educated the public. A few other draftsmen also contributed to his work.

The weed charts have subsequently been much admired, both nationally and internationally. They were used as part of the curriculum in Norwegian and foreign agricultural and horticultural education for decades.

Now the National Library of Norway has published Korsmo's weed charts in the splendid book Ugress. Et vilt herbarium. Emil Korsmos klassiske plansjer. (Weeds. A wild herbarium. Emil Korsmo's classic wall charts.) Liv Borgen has written the texts for each plant.

Borgen has moved away from some of the botanical descriptions to let the detailed drawings speak for themselves. She has chosen to emphasize ethnobotany, or how people have used the plants over time. In addition, she has written about the plants' natural history, the way they spread and where they can be found today.

Intricate roots

Borgen thinks that Korsmo’s definition for weeds was quite nice. He wrote that weeds were plants that grew somewhere you did not want them — a plant in the wrong place.

Korsmo studied how farmers could fight weeds. But it was not easy, and the reason for that is clearly visible in the drawings.

“What particularly fascinates me about the charts is how the root systems look underground,” says Borgen.

The perennial rootstock weeds are the most difficult to get rid of. The seemingly innocent, pretty creeping bellflower (Campanula rapunculoides) is an example.

“It has a thin root at first, and when you have pulled it up, you may think you've got the whole plant. But underneath is a rhizome with several powerful tap roots.

The tap root can actually be eaten and has a nutty taste. The flowers can decorate a salad. The plant was introduced to Norway as a food plant in the 18th century and has also been sold as an ornamental plant.

Goutweed (Aegopodium podagraria) is known for its intricate root system. Even a little piece of the roots from this plant is enough for new ones to sprout in the following year. More than a few gardeners are quite familiar with this particular monster plant.

The field horsetail (Equisetum arvense) is also a "bad guy". It has been used as a medicinal plant, especially for urinary tract infections.

“If you look at the root system, you see why it is so difficult to eradicate,” says Borgen.

Cough medicine for crotchety priests

The uses for these weeds have been many. A good number are edible. Otherwise, the plants have been used as animal feed, spices, dyes and more. Plants were widely used as medicine until the late 1800s, says Borgen.

During the 1600s and 1700s, nettles were grown in several parts of the country. Factories made textiles from the fibres in the stem, she says.

“The stalks of stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) were treated in the same way as flax and produced very fine material,” she says.

Beautiful fabrics, curtains and other things were made of the fibre.

During the same period, hedge mustard (Sisymbirum officianle) was the main ingredient in a popular cough syrup, Borgen says.

“The famous Swedish botanist Carl von Linné wrote that priests who had drunk a lot of beer the night before having to give a sermon, thought it was the best remedy for clearing the head,” she says.

The weed has also been called the singer's plant and tastes like mustard. The seeds can replace mustard in cooking. But the plant may not be so easy to get to know as it is similar to other yellow crucifers, says Borgen.

Coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara) is also on Korsmo's weed list. It was used as a cough medicine, a use suggested by its Latin name Tussilago, where tussi means cough. But not all the plants that were used as medicine in the past were wise to ingest. Coltsfoot, for example, contains carcinogens.

Queen Anne’s lace in your sauce?

Common mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris) was used as food during famine, as a spice in beer, hard liquor and food, as a flour additive and in shoes to protect the wearer from blisters. In Germany, it is still used as a spice in fatty foods.

“In Norway, the flower buds of this terribly ugly plant have been called poor man's peppers,” says Borgen.

It’s probably not that tempting to add common mugwort to bread today. But many of the plants on Korsmo's list are edible.

Borgen has already eaten nettle soup several times this year, and says now is a great time to harvest. The unruly goutweed can be eaten all summer, if the leaves are cut so that new shoots grow.

Queen Anne’s lace, (Anthriscus sylvestris), also called cow parsley, was considered suitable for animal feed, Borgen writes in the book. But in recent times it has become popular with gourmet chefs in the Nordic countries. The leaves are used raw or cooked, or to season sauces. Yarrow (Achillea spp.) is also used as a garnish, in salad and as a spice.

Common chickweed (Stellaria media) is nutritious for humans and animals and can be used in salads. Greater plantain (Plantago major) can also be used in salads, and is best known as nature's bandage.

But Borgen is not so happy to have plantain or dandelions in her lawn, even though dandelion may also be used in salads, and is popular in French cuisine.

“They easily take over,” she says.

Separate the chaff, or the poison darnel, from the wheat

Not all weeds are harmless. Poison darnel (Lolium temulentum) was a dreaded weed that hid in grain fields. Fortunately, it is now rare in Norway.

When there was a lot of poison darnel in the milled grain, it could poison people, causing headaches, dizziness, cramps and, at worst, death.

“The Bible warned against the ‘chaff in wheat’. Now we believe that the warning was about poison darnel, not chaff,” writes Borgen in the book.

Ragwort (Jacobaea vulgaris) is a nuisance for farmers, especially in western Norway.

“It is said that it leaves the country deserted, that is perhaps the reason for the Norwegian name,” says Borgen.

It is poisonous and farm animals can eat it if the grazing is poor. It is toxic even if it is dried and is mixed with hay.

New spring for weeds?

Korsmo learned how difficult it was to eradicate many of the weeds he documented. When chemical herbicides became available, he believed they could be the solution.

“We don’t quite agree with that now. We try to avoid using chemical agents, so that we’re not spreading poisons and destroying the wild flora,” says Borgen.

Some of the plants on Korsmo's weed charts are currently on the Red List for threatened or endangered species. Some are also on the Black List because they threaten Norway’s natural flora.

Korsmo's focus was to fight weeds, but things have changed since then, Borgen says.

“Now we want to preserve biodiversity, which has made popular to use the diversity of plants provided by nature in our food,” she says.

Sociologist Annechen Bahr Bugge, a researcher at the SIFO Consumer Research Institute at Oslo Metropolitan University, agrees. She has written a book on eating habits in Norway from the 16th century to the present, and studies Norwegians' eating habits.

Some types of weeds have come into use more, such as wild garlic, she says.

“Wild marjoram (Origanum vulgare) is called the oregano of the Nordic countries. It’s said that Nordic herbs are a little milder in taste,” she says.

Bugge says that Norwegian food in general has become more popular in recent years.

“We have seen a growing interest in Norwegian food and local products. Norwegian traditional dishes have gained a boost,” she says.

People do not eat "grass"

Norwegians are fond of foraging for food. Annechen Bahr Bugge has documented this tradition and describes it in her book, Fattigmenn, tilslørte bondepiker og rike riddere (Fried crullers, apple brown betty and grilled sandwiches). Fifty-three per cent of Norwegians picked berries during the last 12 months of 2015.

This tradition has not always been common. Berry picking for food and jam first became more widespread in the late 1800s when sugar became cheaper and the 'Norway-jars' which were suitable for jam came on the market, according to Bugge's research.

The researcher says that there is debate over how much people used wild foods in the past. Norwegians were probably not eager to eat weeds. In fact, they didn’t eat many vegetables either. They mostly ate potatoes and grains.

Wild plants appear to have served mainly as herbal and medicinal plants, not as food, Bugge writes in her book. But people were plagued by scurvy in the 18th century and wild plants were considered to be a useful treatment. Poor people used the weeds more often, especially during famines.

Wild greens were eaten very rarely in inland Norway during the first half of the 20th century. People didn't like it very much, she writes in the book.

This is how people in Uvdal in Buskerud reacted when a woman from outside the region had been picking caraway (Carum carvi) : "No, Samuel says that old woman was weird. She was eating grass.”

There were similar descriptions from Elverum. The men would often say that "the cows can have that grass" or "I don't eat grass" when vegetables were served.

Interest in local and Norwegian

Although weeds and other plants have been used for many different purposes, wild plants were not eaten very much in the old days, Borgen says.

“But now people are getting better at foraging for both berries and mushrooms, and for what we could call weeds, or plants in the wrong place,” she says. “Then you begin to see the value of not destroying all the places where plants that have been here for a long time might grow.”

Bugge says that researchers are seeing an increasing interest in local food, growing your own food and foraging from nature.

“One interpretation may be that it is ‘naturally’ perceived as an effective solution to the dilemmas that consumers face now regarding health, the environment and ethics. It can also be interpreted as a criticism of industrial food production. It also reflects a little nostalgia — a longing for traditional ingredients, techniques and dishes,” Bugge writes in the book.

“I think the situation with the coronavirus epidemic has not only highlighted this in terms of self-sufficiency and how vulnerable we may be, but I also think we will see that the pendulum will swing even more towards the local and Norwegian,” she said.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

References:

Liv Borgen: “Ugress, et vilt herbarium, Emil Korsmos klassiske plansjer” (Weeds, a Wild Herbarium, Emil Korsmo's Classic Plates), National Library of Norway, 2020.

Annechen Bahr Bugge: “Fattigmenn, tilslørte bondepiker og rike riddere: Mat og spisevaner i Norge fra 1500-tallet til vår tid,” (Fried crullers, apple brown betty and grilled sandwiches: Food and eating habits in Norway from the 16th century to our time), Cappelen Damm Akademisk, 2019.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no