Locally produced food and self-sufficiency remain but a dream for most countries

According to a new Finnish study, almost 80 per cent of the world's population depends on imported food. What does this mean in times of crisis?

The coronavirus crisis makes local food and self-sufficiency more relevant than it has been in a long time: If labour shortages abroad lead to less food production and higher food prices, should countries be growing their own food? And will this really work?

Regardless of crises and food prices, many people are interested in consuming locally produced food.

But according to a new study published in the journal Nature Food, most of the world’s countries aren’t actually able to be completely self-sufficient.

Great variety in what we eat

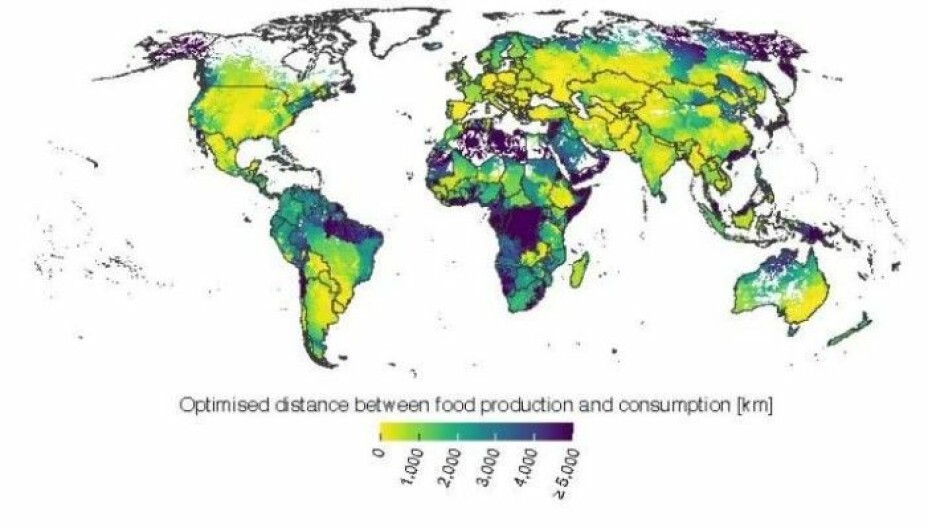

The researchers behind the study calculated the distance between consumers and food producers and figured out how far food would have to travel for people to get what they need.

They primarily looked at plant-based foods and categorized them into six groups: cereals (wheat, barley, rye and oats) rice, corn, tropical cereals (millet, sorghum), tropical root crops (cassava, manioc) and legumes (peas, beans and lentils).

They then calculated the distance between cultivation, production and consumers.

Few people actually eat locally produced food

It turns out that only 27 per cent of the world's population has access to grain products such as wheat, barley, rye and oats that have been grown within a 100-kilometre radius.

Only 22 per cent has access to locally produced tropical cereals. Twenty-eight per cent has access to locally produced rice, while for legumes that proportion is 27 per cent. When it comes to corn and tropical root crops, only 11 to 16 per cent can buy these foods locally.

But there are big differences. In Europe and North America, most people live within a 500-kilometre radius of wheat crops.

In comparison, the global average is about 3,800 kilometres.

"This illustrates how difficult it is to depend solely on local resources," says Pekka Kinnunen, a researcher at Aalto University in Finland and one of the study authors, in a press release.

100 kilometres is not enough

In other words, locally produced food is not something most of us can take for granted. The study shows that for the majority of the world's population, up to 64 per cent, the distance between producer and consumer is more than 1,000 kilometres.

But what exactly is locally produced food? How near to the consumer does food have to be grown and produced before it is — or isn’t — considered local?

Karen Syse, a researcher at the Centre for Development and the Environment at the University of Oslo, is critical of the researchers’ decision to use a radius of only 100 kilometres as the cut-off for what can be called local food production.

“In Norway, there would be a lot of coffee-thirsty and bread-hungry Northern folk if all food were to be produced within such a limited radius,” she says.

She believes national boundaries are better than a 100-kilometre radius in terms of defining whether food can be considered locally produced or not. If a country manages to produce enough food to feed its own population, that country can be considered self-sufficient.

A lot of foreign food in Norway

Self-sufficiency is a hot topic in Norway right now. The Norwegian Agricultural Cooperatives claim that Norway’s self-sufficiency rate is just under 50 per cent, but the group did not include fish in their calculation. Prime Minister Erna Solberg has even said that if all the fish produced in Norway were included, the country can be considered 100 per cent self-sufficient, according to the website Faktisk.no.

This number is also contested, however, because it includes the import of animal feed, which is used to produce human food.

In 2018, Norway imported barley and wheat from Russia, Kazakhstan, China, Germany, France, Belgium, the United Kingdom, Sweden, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands and Denmark, according to numbers from The Royal Institute of International Affairs.

“We have been dependent on grain imports in Norway for a very long time,” Syse says. “Even during the Viking era, dried fish was traded for grain.”

Today, Norway imports three times as much food as it did in 2000, according to figures from the Directorate of Agriculture. Norway imports everything from vegetables, potatoes, fruits and berries to dairy products, meat and cereals.

Food choices play a part

But we also produce a lot of these foods in Norway.

“Food systems are so incredibly intricate,” Syse says. “Everything is connected to everything, from production and processing to transport, import and export.”

There is also a big difference between what people like to eat and what people need to eat. For example, the researchers behind the study have calculated how much rice is needed in Norway.

“But Norwegians have managed without rice for many hundreds of years,” says Syse.

“If we would eat more porridge and flatbread made from the grains we grow ourselves, such as barley and oats, rather than feed them to animals, we would have a much greater degree of self-sufficiency when it comes to agricultural products,” she says.

Malawi and the sweet potato

Karen Syse has been interested in the African country of Malawi and how it has changed its approach to food production. She believes the country is a good example of a place that previously cultivated food for its own population, and which now primarily grows food and other goods to sell to other countries.

Malawi used to have more diversity in its food production, including sweet potatoes and 15 types of beans. The sweet potato contains a lot of vitamin A, which is lacking in many African countries.

Farmers cultivated sweet potatoes in the shade of the forest, which resulted in very good growing conditions.

“Now they cut down the forest and grow mostly corn, sugar, tobacco and tea,” says Syse.

This exposes the country to fluctuating commodity prices and puts them in a weak position on the international market.

Today, Malawi is one of the poorest countries in the world, where almost 30 per cent of the population is malnourished, according to UN figures.

What happens in times of crisis?

“When all is said and done, we cannot opt out of the world completely,” says Syse.

She believes that international cooperation and trade should be combined with self-sufficiency to ensure strong food security.

"If a disaster like Chernobyl makes our food inedible, we have a very big problem if we can't import," she says.

The Finnish researchers also point out that local food production makes a country vulnerable.

If a country tries to rely solely on local food production, it can put extra pressure on the environment in highly populated areas, such as water pollution, loss of biodiversity and over-consumption of water resources.

In addition, a shift towards local food production can make us more vulnerable to migration, crop losses and an inability to cover all our nutritional needs, according to the researchers behind the study.

A delicate balance between imports and local food

Against this background, the Finnish researchers believe that we need a flexible system where we both trade in food, but do not become totally dependent on it.

“The coronavirus pandemic is a disaster that opens our eyes to food security. Although we are doing well in Norway, a shortage of labour abroad can result in less food production and higher food prices,” says Syse.

“And when suddenly neither German nor Norwegian farmers have access to cheap labour from Lithuania, it’s a reminder that we either depend on a global labour market, or that we have to roll up our sleeves and grow the food ourselves,” she says.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

References:

Pekka Kinnunen et al.: Local food crop production can fulfil demand for less than one-third of the population. Nature Food. April 2020. DOI: 10.1038/s43016-020-0060-7. Summary

Resourcetrade.earth Chatham House. The Royal Institute of International Affairs.

———