Researchers to test giving blood from recovered coronavirus patients to the sick

Researchers at Ullevål University Hospital are reviving a 100-year-old method from the 1918 influenza pandemic.

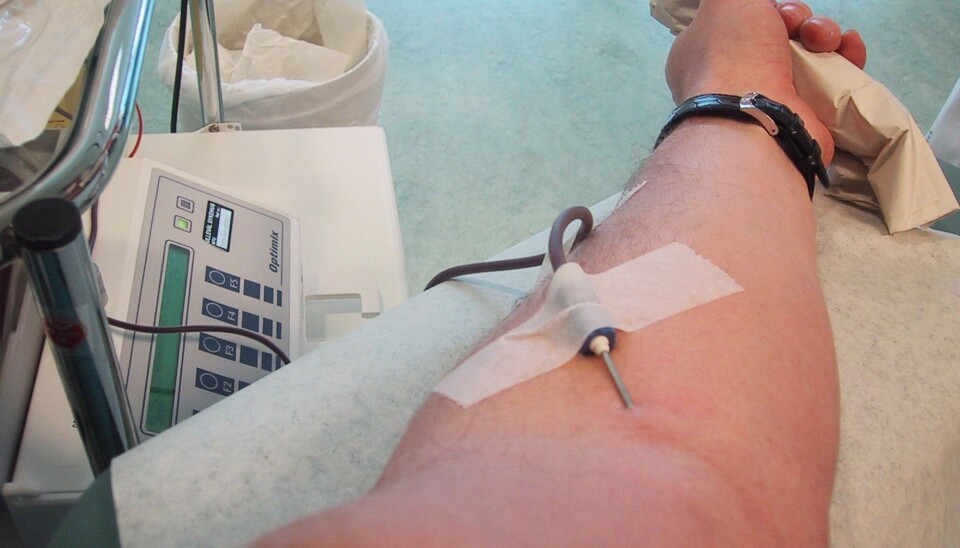

Blood from recovered coronavirus patients will be given to sick patients.

The trials are likely to begin shortly.

On Friday, March 27, Lise Sofie Nissen-Meyer, senior consultant at the Blood Bank at Oslo University Hospital (Ullevål) met with representatives of the Norwegian Directorate of Health, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, microbiologists and the largest blood banks in Norway to discuss this new coronavirus project.

“We are very interested in finding out if this works,” she said to forskning.no.

And she would like to get started as soon as possible on what will become a national project.

Will transfer antibodies

This is not a vaccine.

The researchers at the Blood Bank at Oslo University Hospital will instead try to find out if antibodies found in the blood of people who have recovered from Covid-19 can help new coronavirus patients.

One hundred years ago, researchers at the time tried the same technique on patients affected by the 1918 influenza pandemic, also known as the Spanish flu.

The conclusion at the time was that it worked. But research from a hundred years ago cannot necessarily be assumed to be valid today.

Tried on measles and swine flu

The method was also said to have been used successfully during a measles outbreak in the United States in 1934.

During a small trial of 93 patients who became very ill during the 2009 swine flu outbreak, researchers found a significantly lower mortality rate among those given blood plasma with antibodies, compared to a control group that did not receive blood with antibodies.

Patients who were given blood plasma with swine flu antibodies suffered less severe respiratory tract infections. A severe overreaction of the immune system, which is also seen in Covid-19 sufferers — the cytokine response — was substantially reduced.

Essentially, people who were given the treatment were less likely to die.

Possible treatment in a short time

“The method has been tried on several types of infections throughout history with varying results. But almost all the studies we have are old,” said Nissen-Meyer. “That’s why we’ll test this now.”

The researchers at Oslo University Hospital are working intensively to plan the new study, so that it can show whether the blood plasma treatment has the desired effect and whether it is safe.

Nissen-Meyer believes that the treatment could be something to offer to coronavirus patients as a stop-gap measure before a possible vaccine is available.

National cooperation between blood banks

Norway’s blood banks agreed Friday to cooperate on the research project.

The blood banks have agreed that they will be able to deliver plasma products if the doctors treating the coronavirus patients will try them out.

“The hope is that people who become sick with Covid-19 will recover faster when they are given antibodies from this blood,” said Nissen-Meyer. “If that is the case, this is also a way for us to reduce the number of intensive care patients who are severely affected by the virus.”

But first, the researchers at the Blood Bank must make sure that what they do is safe enough.

Need donors who have recovered from the disease

Hans Erik Heier is a retired professor of transfusion medicine at Ullevål University Hospital.

“One challenge is that we need enough people who have recovered from Covid-19 to get enough blood. It is not justifiable to use blood from someone who has not fully recovered,” he said.

Otherwise, these blood donors will likely have to meet the same criteria that blood donors normally have to meet.

Blood from ten people

Heier explains how this will work.

“The antibodies in the blood are like large egg whites. These bind to the coronavirus. Then they enable the body's own cells to absorb the coronavirus and destroy it,” he said.

Heier says that during the Spanish flu, doctors simply took blood from a healthy person and gave it to another ill person.

In this effort, however, researchers will mix blood plasma from ten different recovered coronavirus patients and give the combination to the sick person. This will better allow them to assess the effects of the treatment.

Being tested in Denmark, USA and China

A research group at the Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen is now ready to embark on a similar experiment.

“People who have survived the new coronavirus have antibodies that precisely target this virus,” said Jens Lundgren, professor of infectious medicine, to the Danish newspaper Kristeligt Dagblad.

At the forefront of the use of blood antibodies to fight the coronavirus may be a research group at Johns Hopkins University in the United States. There, immunologist Arturo Casadevall says it’s not necessary to study the treatment before starting it.

"It could be deployed within a couple of weeks since it relies on standard blood-banking practices," he said in a press release from the university.

Casadevall says the technique will need strong organization, enough resources and of course former coronavirus patients who are willing to donate blood.

Casadevall also noted that clinical studies will be needed to determine the most effective way to deliver the treatment. “We will learn new science from this calamity,” he said in the press release.

John Hopkins University also reported that Chinese researchers are already providing antibodies to infected coronavirus patients. Early results from China appear to be promising.

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk

Sources and references

van FN Hung et al: “Convalescent Plasma Treatment Reduced Mortality in Patients With Severe Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) 2009 Virus Infection”, Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2011. Article.

Kristeligt Dagblad: “Danske læger kigger mod fortiden i jagten på en behandling af coronapatienter” (Danish doctors look to the past in the hunt for treatments for coronavirus patients), 18 March 2020.

Science Alert: “Johns Hopkins Experts Are Trying a Clever Antibody Method From The 1890s on COVID-19”. Article.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no