Right Now!

Violent extremism is not a uniform phenomenon: The key differences in prevention of left-wing, right-wing, and Islamist extremism

Policies to prevent radicalization and violent extremism frequently target militant Islamists, right-wing and left-wing extremists. In a recent study we have examined what distinguishes the ways in which local practitioners perceive and respond to each of the milieus. Our results show that there is a clear discrepancy between the uniform way violent extremism is presented in policy, and how front line practitioners experience the different forms of extremism at the local level.

In many Western democracies, the policies to prevent radicalization and extremism often bundle together militant Islamist extremism (MIE), right-wing extremism (RWE), and in many cases left-wing extremism (LWE). These distinct phenomena are referred to under the common label of “violent extremism”, emphasizing commonalities and downplaying their differences.

In contrast to the uniform understanding often conveyed in policy documents, we examined what distinguishes the ways in which public servants actually perceive and respond to the three milieus, and how these differences could be conceptualized. To do this we conducted in-depth interviews with twenty-seven public servants in Sweden, mainly frontline practitioners involved in local preventive work.

Our results make evident how the milieus are seen to differ in three crucial respects.

They:

1) Represent different levels and types of threats.

2) Hold core values that resonate differently with dominant values in mainstream society.

3) Involve different challenges for the employment of counter-measures.

The different milieus as different threats

The three milieus were described by practitioners as markedly different in the level and type of threat they represented. By level of threat we mean the extent and intensity of activity, and by type of threat we refer to the forms of political violence used by each milieu.

MIE was primarily described as a sporadic, indiscriminate and “invisible” threat, connected to few, albeit horrific, terror attacks targeting civilians.

RWE was often seen as an ongoing, visible threat, primarily responsible for violence and hate crimes targeting specific groups, as well as continual challenges to local democratic institutions in the form of threats and confrontational behavior.

In the interviews, LWE was rarely considered an issue at all, and not seen as a prevalent threat in local settings. When mentioned, LWE was primarily connected to property damage, counter-demonstrations and disturbance of the public order.

For many of the practitioners, the experienced high level of threat associated with RWE often came into conflict with extra-local prioritizations and expectations of working primarily on MIE. This created discord for some practitioners, as they felt pushed into carrying out a mission in which they did not fully believe or feel aligned with.

The differing core values of the milieus

The practitioners differed markedly in their views about the core values of LWE, RWE and MIE milieus, and they also situated them differently in relation to what they saw as dominant values in Swedish society.

MIE was seen to represent the biggest clash with mainstream values, followed by those of RWE. Numerous practitioners described the core values of the LWE as more aligned with those of the wider society, and rather represented a radicalization of mainstream values.

The different core values of each milieu was seen as decisive for the degree of social exclusion and marginalization activists faced in wider society. While the interviewees expected that members of MIE and RWE milieus would be heavily stigmatized, LWE activists were seemingly much less so.

These perceived differences also seem to affect how practitioners think and reason about the possibility of different counter-measures. When practitioners discussed counter-measures against LWE, they focused primarily on behavioral change, not cognitive change. It was the violent practices that were considered problematic, not the radical beliefs themselves.

Regarding RWE and MIE, both beliefs and practices were deemed problematic and dangerous. The counter-measures highlighted by practitioners thus often involved the individual disengaging from their social context as well as changing behaviors and ideational beliefs. These de-radicalization efforts were seen to take up more resources, as they often entailed helping the individual to a new life, including finding a job or housing, social care, and pursuing education.

The different challenges of responding to the milieus

Regarding challenges, practitioners experienced the milieus to differ along three main lines:

1) the potential for exit and re-integration,

2) the entry points for preventive measures, and

3) the signs of radicalization.

According to the experience and views of practitioners, exit and re-integration were often unproblematic for activists from LWE milieus, while the RWE and MIE carried out much more stringent sanctions towards defectors, which often involved personal risk and major life and social changes for those wanting to leave.

The interviewees also emphasized the uneven availability of exit programs. In relation to RWE, practitioners frequently referred to already existing institutions for exit-work. With regards to MIEs, practitioners more often connected exiting to traditional social work, by targeting individuals, their social networks and the communities they lived in. The interviewees offered no examples of LWE, and exit measures were neither described as a priority nor a necessity.

With regards to entry-points, interviewees described individuals engaged in RWE or MIE as often having a range of interconnected social problems, from social exclusion and mental illness, to drug abuse and criminal behaviour, to living in socially and economically deprived communities. These social problems sometimes opened avenues for personal contact.

Persons affiliated with LWE were generally described as coming from the middle or upper class, as being more educated, socially connected, well off economically, as well as living in stable communities, which often left front-line practitioners with few or no accessible entry points.

Concerning signs of radicalization, practitioners expressed varied knowledge of the three milieus, where the challenge of identifying signals connected to MIE and the lack of knowledge on LWE stand out as particularly evident.

In sum, the practitioners seem much more inclined to react to views, signs and indicators associated with RWE and MIE, compared to that of LWE. This was partly because of their varied knowledge about each milieu, but also due to the hardships of making a distinction between “normality” and the “extreme”.

When the values of members of militant milieus are closer to that of mainstream society, it is more challenging and makes less sense to try to identify signs of cognitive radicalization, as these ideas do not stand out as much as within milieus that hold fundamentally anti-democratic or anti-egalitarian values.

Conceptualizing differences across the milieus

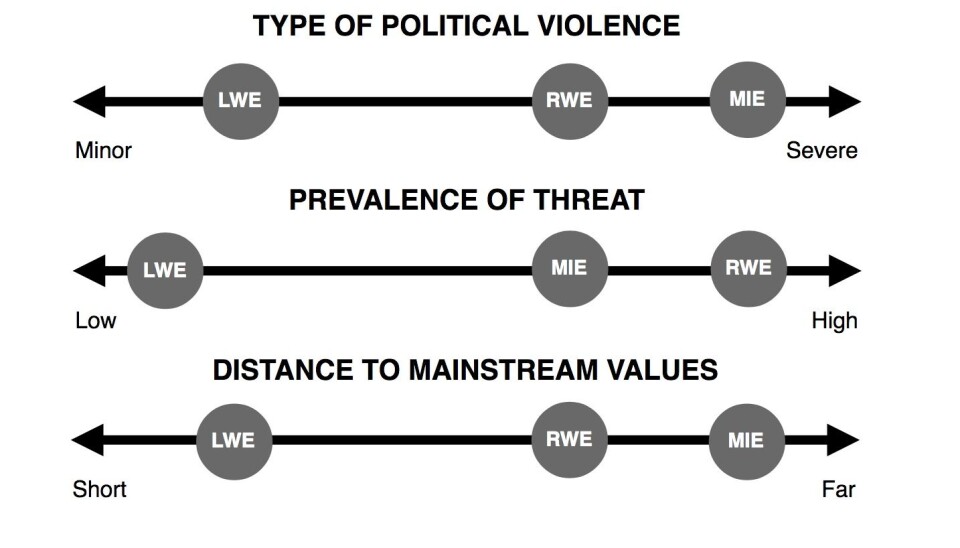

Summing up the ways in which practitioners relate to the targeted milieus enables us to draw a model of three key continuums, or dimensions, along which extremist milieus might differ. Positioning the milieus on these continuums helps explain why local practitioners perceive and respond differently to them, while also providing an aggregated image of the experienced key differences across the milieus.

The first dimension (level of political violence) concerns the type of threats associated with each milieu, and thus reflects the perceived severity of the violent actions or tactics.

In our case, the continuum ranges from lethal terrorist attacks and threats to national security (severe), to violence against individuals and threats to local democratic institutions (medium), to issues related to property damage and disturbance of public order (minor).

The second dimension (prevalence of threat) encompasses the level of threat associated with different extremist milieus, and thus the extent and intensity of their activities. The placement is often based on the public visibility of the milieus and the number of attacks, actions or public protest events they stage.

The third dimension (distance to mainstream values) sets out the degree to which the core values of each milieu are seen to resonate with the values held in mainstream society. Our analysis shows that this dimension also corresponds with the level of social sanction and exclusion that those (previously) involved in each milieu face from mainstream society, where a short distance to widely shared values involves a low level of social stigmatization.

Based on the local practitioners’ assessments at the time of the interviews, we have situated the three milieus on the continuums of each dimension (Figure 1).

The LWE milieu is situated towards the left end on all three dimensions. Regarding the other two milieus, for the first (level of political violence) and third (distance to mainstream values) dimensions, the MIE milieu is positioned at the outer right end and the RWE milieu between the middle and outer right.

The only variation to this pattern is the second dimension (prevalence of threat), where RWE is positioned towards the outer right end and MIE between the middle and outer right. This positioning reflects the fact that practitioners, at the time of the interviews, often described the prevalence and activity of RWE as representing a higher level of local threat than that of other milieus.

In sum, our study finds a substantial discrepancy between the uniform image of radicalization and violent extremism often presented in policy and the complexities practitioners experience when they address these phenomena across extremist milieus.

Secondly, the three targeted milieus are seen to differ in crucial respects: the type and level of threats they represent, their core values and other internal characteristics, as well as their position vis-à-vis society at large.

Our study thus shows how a simplistic presentation in policy is unhelpful and misleading both for understanding the targeted milieus and the complexity of local preventive work.