Tiny Arctic wildlife matters

Hello from another fine day from the largest research vessel in Norway - Kronprins Haakon. After having a delicious pizza lunch on board today, I came up to the 7th deck (yes that’s right, this boat has 10 decks), to write this blog in the conference room – a nice, cozy room with a great view. How is a girl from the south of India where winter is 20 degrees, surviving up here in the Arctic, you ask?

Its hard to believe for many (including my mother) that I am all about the winter, and its way before “The Starks” from The Game of Thrones. Today is the 11th day at sea, and we are at the Process station 5 (P5) out of 7 stations of the Nansen Legacy transect in the northern Barents Sea. It is our second day here and we are waiting to retrieve the sediment trap for Yasemin – another PhD student from UiT. Which brings me to introducing myself – I am a PhD student from The University Centre in Svalbard, my name is Cheshtaa and I’m working on small organisms, so small that you would need microscopes to determinate what they are.

I am here to answer an important question – what am I doing on this massive beautiful vessel for 3 weeks falling (sea) sick on the wavy days? I am an affiliated member of the Nansen Legacy project, one of the biggest marine-based Norwegian collaborative research. It brings together universities and institutions all over the country, with early career researchers and established scientists all aiming to understand the Arctic Ocean a little bit more.

But why this much obsession with the ocean you ask? Keeping my opinion aside, if not for the ocean, how else do you think life would have thrived on this planet? We have a wide range of interesting topics covered on board, such as studying the smallest organisms responsible for life in the ocean and understanding effects of toxic pollutants on them. Moreover, we also study changes in sea ice thickness and conditions over the past few years as well as mapping future scenarios with current conditions.

This is my very first cruise for this project, and I am not sure how accurately I can describe all parts of the project that my friends are up to everyday, but I hope I can do justice to at least one of them that I am responsible for.

One of the most important things I figured out on board was that you always have to be on stand-by for work. That is because when you are on board for such a huge national project, you need to prepare, to work, work and work – with administered rest breaks of course. It doesn’t matter what day of the week it is or what time of the day. Fridays are not Fridays anymore, they’re just days, to finish your work. I learned that pretty quick in my first week, when I had to wake up at 1:45 am for my work. Yes, finally, coming back to what I do on board, I filter close to 100 litres of water at every station. You might not think of it as glamorous as the fish biologists or those who we call the zooplankton people, but we are pretty important too you know. In a conversation with the First Officer on board, when I described to him what I am doing on Deck 3 (it’s where we have all our labs and rooms to rest), he immediately said- “oh of course, what you do is very relevant, because if we don’t have your organisms what will the big fish eat?” At this point I’m sure I radiated a thousand lumen light from my eyes (brighter than my brightest headlamps) quietly watching him in admiration, to which he said- “are you okay?”. With a smile on my face I said – I am now. It is hard to explain sometimes that something we cannot see can be so important and why. Small things matter. I mean we haven’t really seen outer space or aliens, but those topics somehow always steal the show.

My job on board is to collect water samples for a type of analysis called metatranscriptomics, which we use to get a snapshot of the smaller fraction of pelagic communities. In scientific terms, gene expression of eukaryotic communities gives an idea of what is going on in the community at that point of time. I am also filtering water for a type of analysis called metabarcoding (see previous blogpost), which is to check the diversity of microbial communities and how it changes based on the different environmental conditions. This gives an idea of the types and different size ranges of organisms we can see in that cross section of the ocean. After filtering we snap-freeze the filters in minus 80 degrees Celsius, in order to take it to our universities/institutes for further laboratory analysis. What we do with these filters is a process called DNA extraction. DNA as we know is the building block of life; it’s what is passed on as genetic material from a parent to an offspring. This tedious 5-6 hour procedure gives us a teenie tiny amount of transparent liquid, which contains the DNA of microbial organisms. This DNA has all the information we would need to know about the whos who of the microbial kingdom of our P stations. We then send this off to a company to further process our transparent liquid into computerized results, which we try to interpret.

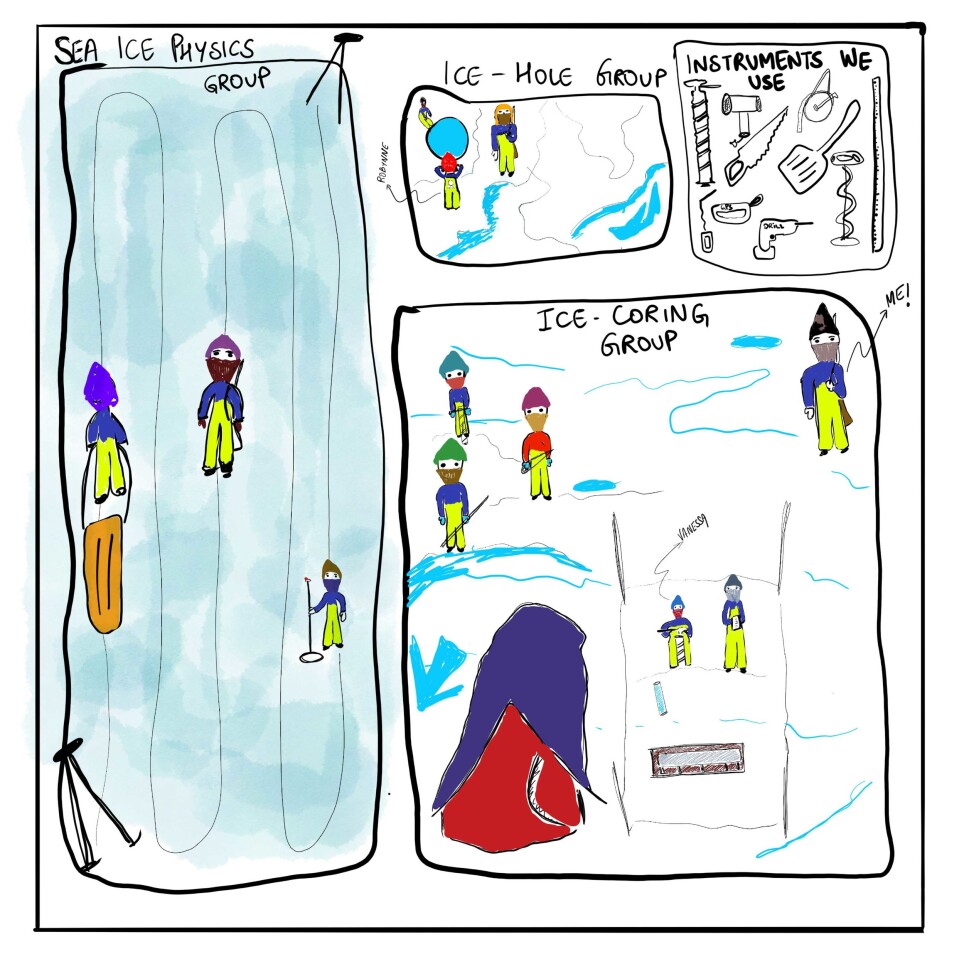

Mind you, we don’t just sample water, we also sample the ice by taking ice cores. Our first large ice station was on P4, which was something I had not seen before. For the ice station at P4 we had to plan at least 24 hours ahead of what exactly we were going to do. This was to ensure most efficiency in a short amount of time. At this station, I was asked to be the polar bear guard for the first half of the day, not very surprising as I come from Svalbard, and have had the “polar bear guarding experience” for almost 2 years now. It wasn’t “that cold” outside when I first stepped outside on deck in my regatta suit and 2 layers of wool underneath. I was sweating profusely even before starting work. The polar bear guards got a safety brief with the head of polar bear safety – Jørn from NPI (Norwegian Polar Institute) in Svalbard, half loaded the rifles and swore to protect our comrades. Like a straight line of ants walking onto the ice we diverged into 4 smaller groups. The first one was the sea ice physics group, which was going the furthest away doing transects on sea ice to measure its thickness and other properties. The second group lead by my very good friend Robynne (UNIS) was in charge of the water hole, where we were going to sample water – untouched by the ship. The third and the fourth group were both ice coring groups, which I was responsible for guarding. These groups were responsible for taking almost 44 cores. Now that’s a task! 44 ice cores, while measuring their length, sawing them up into different sections, measuring the level of water that they came out from and ensuring all of those core buckets get on board ASAP to start with the melting. This could not have been possible without the planning of the three most efficient people that I have met in my life- our cruise leader Sebastian from NPI, co-cruise leader Anette from NPI as well and Miriam – the Nansen legacy engineer from UiT. Miriam planned the ice work, and divided everyone in teams to collect and process the core samples, and the cruise leaders made sure everything went as planned from the bridge. The cruise leaders were in were in fact our first polar bear watch, having a view until the horizon to look for any incoming danger.

Soon after lunch, I was shifted to the ice core team to learn how to retrieve ice cores, and saw them without contamination. Ice coring, I quickly learned, was a skill that one should have in the Arctic especially when taking samples every month for their PhD- le me. My other very good friend and Svalbard acquaintance Vanessa taught me how to ice core. I would like to call her the ice core queen, each cores more perfect than the last one. And if you get to learn from the best, you will start off good at least. And I DID! My second ice core ever was not broken and straighter than Natalie’s hair (another PhD student with very straight hair). It was what the kids are calling it these days- PERFECTION. Maybe that’s a bit too much for an ice core, but Vanessa in her own words said – “Wow Cheshtaa! This is so good!” I even remember the length of this ice core being 54 cm. We measured the ice core temperature at every 10 cm and noted it down. While we were being successful making our little cores we got an order from the bridge at around 4 pm to get back on board, as there was a polar bear coming in our direction. Thankfully, our ice work was all done. All we had to do was pack up and head back.

We all headed back and watched the polar bear from the day lounge on board. Those huge windows on the side of the boat with 35 pairs of eyes glued on to see what the bear would do next is what I live for. Curiosity. This is what makes Science what it is. This is why I got into Science. The polar bear made it to the amphipod traps set up by my friends and started to chew on it – probably because of the horrid smell of dead polar cods that were used as bait. Did you know that polar bears could smell up to 30 km! That is something I knew but witnessed that day for the first time. When it got bored of chewing on the amphipod trap, it went on to the set-up of the sea ice physicists and just sat there and chewed up on their instrument bags. With a high definition camera we could see what it was chewing on while it was sitting there like a cute little puppy. Yes I find them cute, and not see them as the carnivores they are.

Our day ended finding out, after the bear had left, that none of our instruments on ice recording our measurements were damaged, and only some of the protection/packaging of the instruments was slightly ripped.