Right Now!

CasaPound Italia: Contemporary Extreme Right Politics

How does a relatively small far right group, with little electoral support, attract international media attention and influence national politics? A recently published book by C-REX researchers Pietro Castelli Gattinara and Caterina Froio uses the example of CasaPound Italia to illustrate the new and often surprising forms that right-wing extremism is taking across the globe.

CasaPound Italia (CPI) is a street-based far right group, which was born with the occupation of a building in Rome, and which makes no a secret of its appreciation of Benito Mussolini’s regime.

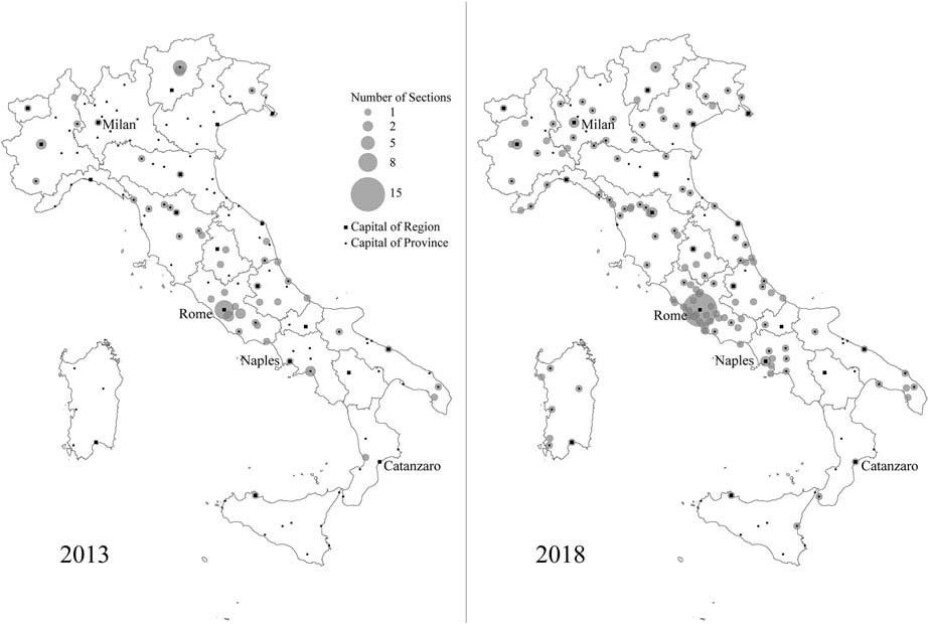

Despite its grassroots nature and extreme ideology, over the past years CPI acquired national relevance and international media exposure. In the last five years alone, the group opened 94 new local chapters (see Figure 1 below), successfully penetrating mainstream public debates and receiving disproportionate attention by mass media and commentators in Italy and beyond. The visibility of CPI symbols, campaigns and brand among mainstream audiences are unprecedented for a fringe group so openly inspired by historical Fascism.

How did such a small far right group, with little electoral support, manage to attract international media attention and influence national politics?

Why hybridization can explain the success of fringe far-right groups

In the recently published volume CasaPound Italia: Contemporary Extreme Right Politics, co-authored with Giorgia Bulli and Matteo Albanese, we introduce a theoretical framework to understand how, when and why fringe far-right groups may succeed in making their extremist ideologies attractive beyond traditional extreme right circles.

Groups like CPI, in fact, may obtain high-profile public attention by means of what we call hybridization strategies, i.e. the strategic combination of organizational features and activities inspired by different political cultures, institutional party politics, and non-institutional contentious actions.

Specifically, we argue that the success of CPI has to do with the blurring of five main aspects of extreme right politics: ideology, internal structure, activism, mobilization and communication.

These five features of CPI politics are blurred as they display elements mediated from different political cultures and from the tradition of both political parties and social movements. Hybridization in these five main aspects of extreme right politics allows attracting quality media attention while also validating extremist views in the public sphere.

To corroborate this claim, we triangulated a wide array of qualitative and quantitative data, collected over more than five years of fieldwork in different cities in Italy, integrating open observation during public events, semi-structured interviews, as well as content analytical data from music, news and social media material.

Ideology: at the crossroads of historical Fascism and ethnopluralism

CPI's ideology is not fully entrenched in Fascism but it is not disconnected from it either, as it is indebted to various strands of historical and post-war Fascism, including Destra Sociale and Nouvelle Droite.

Rather than dismissing all references to inter-war and post-war worldviews, CPI uses the concept of ethnopluralism to attain ideological coherence. Ethnopluralism offers a consistent framing of core themes – like social welfare and globalization – as well as issues considered of secondary importance – like gender and the environment.

Hybridization thus allowed CPI to emphasize its ideological roots in the tradition of the extreme right, while avoiding stigmatization as being outdated or openly racist.

Internal structure: the movement-party model

The internal structure, decision-making and recruitment of CPI does not fully conform to either the model usually followed by electoral actors, or that of grassroots organizations.

Rather, it combines formal and informal features, hierarchic procedures and spaces of socialization, merging the organizational practices of social movements with those of formal political parties.

The coexistence of these two organizational models crucially contributed CPI’s capacity to draw financial resources and personnel from different venues, and to offer both conventional and unconventional modes of political participation for militants and sympathizers.

Activism: a composite mix of different political cultures

Activism in CPI rests on images, styles and practices borrowed from different political cultures.

These include extreme right identifiers (Mussolini, music in the form of ‘identity rock’ and violent narratives and practices), but also left-wing icons (e.g. Che Guevara and Karl Marx) and a set of aesthetic codes concerning activist clothing and the group’s imagery.

This hybrid stylistic repertoire is crucial to CPI’s public profile, as it contributes to reducing stigmatization by outsiders; it facilitates the recognisability of the group by potential sympathizers; and it actively sustains the identification of individuals within the group.

Mobilization: within and without the electoral arena

The repertoire of action of CPI combines activism inside and outside the institutional arena, including electoral campaigning, grassroots actions and agitprop operations.

The group does not consider protest tactics a suboptimal option compared to office-seeking strategies, but complementary to party competition. In this respect, CPI seeks to maximize media coverage by transposing the logics of damage into the electoral arena, and those of party competition into the grassroots extreme-right milieu.

Communication: professionalised media-oriented tactics

The communication strategy of CPI combines the professionalized media-oriented tactics of both political parties and social movements and allows the group to get coverage for both protest and electoral activities in quality media.

More specifically, CPI’s variegated media infrastructure has enabled the group to become recognizable not only among far-right sympathizers but also among the broader public. Its particular communication style builds on simplified messages and agitprop campaigns, meeting the mass media demand for sensationalistic and entertaining stories. This hybrid communication repertoire allowed CPI’s fringe narratives to become part of mainstream public debates and media coverage.

As political circumstances change, so do extreme-right politics

Through hybridization the far right may adapt to liberal democracy, with the goal of radicalizing mainstream ideas and audiences. This strategy granted CPI leeway for the diffusion of its ideas and campaigns among a wider public than the (restricted) audience responding to right-wing extremist messages. In this respect, our theory may help understand how other fringe far-right groups are drifting into mainstream public debates.

Not only CPI, in fact, but all far-right groups need to find resources to sustain collective action, notably money, staff and members.

Hybridization strategy allow the strategic differentiation of the venues addressed to gather financial resources and potential members, combining electoral politics with unionism, community engagement, as well as subcultural activities maximizing the group’s efforts to find resources, both financial and in terms of recruitment and membership.

Furthermore, all fringe groups need to achieve the recognisability necessary to capture wider support. Hybridization strategies allow building distinctive group profiles made of a few, clearly identifiable elements, appearing more extremist than the radical right in the electoral arena, but more credible than old-fashioned extreme-right groups in the protest arena.

The observations included in this volume about CPI’s hybrid politics might thus serve as a first step for further research into electoral and non-electoral manifestations of far-right politics, in Europe and beyond.