Brazil’s declining climate ambitions: A severe blow to global climate governance

The new Brazilian government’s seeming neglect of the climate issue causes instability in international climate negotiations, and puts pressure on other large economies like India and China to help fulfil the goals of the Paris Agreement, argues GLOBUS Researcher Solveig Aamodt. But are these countries up to the task?

Since hosting the UN Environmental Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, Brazil has viewed itself as a leader in global climate governance. Perceived as a tough and well-prepared negotiation partner, the Brazilian delegation to the annual Conferences of the Parties (COPs) under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has consistently argued that developed countries should take the main responsibility for climate change mitigation.

As a member of the BASIC group (Brazil, South Africa, India and China), Brazil has pushed for a more bottom up organisation of international climate commitments and argued that historical emissions should be taken into account when deciding on countries’ mitigation responsibilies. The BASIC countries have emphasised the importance of parties’ autonomous right to decide their own mitigation pathways, but have also insisted on developed countries’ obligation to mitigate.

Brazil has prioritised domestic climate science and made important contributions to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). It has also had a great impact on climate negotiations with suggested global climate governance solutions like the Brazilian Proposal from 1997, which is still a point of reference to negotiators. Brazil was the only BASIC country to join the High Ambition Coalition during the Paris negotiations. Brazil has also lived up to its ambitions by reducing its greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation drastically since 2004, and by being one of the few developing countries with absolute mitigation targets in their Nationally Determined Contributions to the 2015 Paris Agreement.

Jeopardizing Brazil’s role in climate governance

The victory of Jair Bolsonaro in the 2018 presidential election, and his appointments of Ernesto Araújo as foreign minister and Ricardo Salles as environmental minister have jeopardized Brazil’s active role in global climate governance. Bolsonaro has argued that the Paris Agreement may be a threat to Brazil’s sovereignty, and in November 2018, Brazil withdrew its candidacy for hosting the COP25 in 2019. Confirming the government’s lack of climate ambitions, foreign minister Araújo has called climate change a leftist ideology created to decrease the power of capitalism. After a few weeks in office, environmental minister Salles communicated that cooperation between the environmental ministry and NGOs will be put on hold for three months, which endangers the continuation of important environmental and climate protection projects.

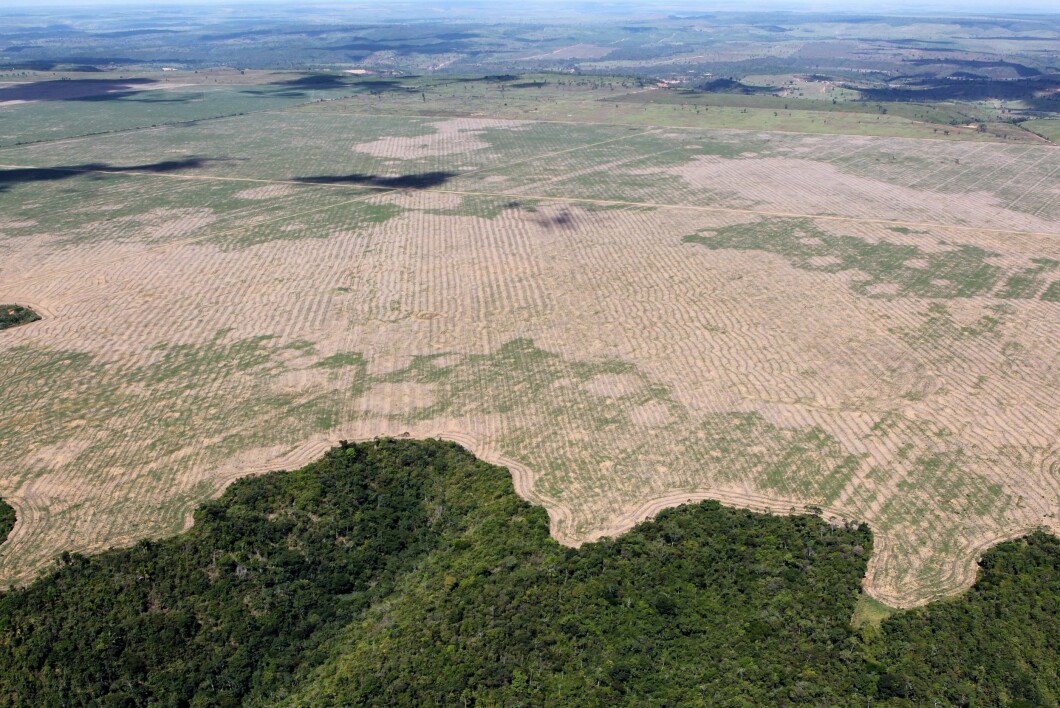

In Bolsonaro’s government, the climate departments in both the foreign and environmental ministries have been discontinued in tandem with organisational rearrangements that highlight the government’s priority of agribusiness, resource extraction and national sovereignty above environmental protection, indigenous peoples’ rights and international climate responsibility. If this development continues, deforestation in Brazil is likely to increase significantly. It thus seems quite unlikely that the current government will be interested in maintaining Brazil’s international climate role. How does this development influence the overall possibilities of reaching the Paris Agreement’s ambitions?

A void in global climate leadership

These developments cause uncertainty about Brazil’s willingness and ability to fulfill its own national climate targets. Combined with the United States’ announced withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, the recent developments in Brazil create a void in climate leadership, and increase the pressure on other large emitters to ensure advancements in global climate governance. South Africa has recently concentrated mainly on its alliance with other African countries in the climate negotiations, but the world’s largest and third largest greenhouse gas emitters, China and India, face increasing pressure for global climate leadership. Together with the European Union, the two Asian giants made great efforts to be vocal and visible at COP24 in Katowice last December.

Can China and India save Paris?

China has been perceived as more willing to take on global climate leadership after its climate deal with the United States in 2014, but European countries and NGOs still regard India as a more unpredictable (and unwilling) actor in global climate governance. The Indian government sees climate change as part of the larger challenge of global structural inequality, for which Western countries are mainly responsible. This view collides with the European preference for addressing climate change as a primarily scientific and technical issue.

However, India has taken new initiatives both domestically and internationally to limit own emissions growth, for instance by upscaling domestic wind and solar power targets and establishing the International Solar Alliance. Because India has a relative low level of per capita emissions, the country’s large push for new renewables is also viewed to be closer to the efforts needed to reach the Paris Agreement’s temperature ambitions than the current efforts of both China and the EU.

Nevertheless, stable intentions of limiting emissions-growth in China and India will not be enough to balance out the potentially large increases in deforestation in Brazil. China, India and the EU all have domestic constraints to significantly ratcheting up their climate actions before 2030. China and India’s contributions may be enough to keep the international process moving (slowly) in the right direction, but not enough to halter the climatic changes. Without Brazil, a large piece of the global climate governance puzzle is missing.

Can Brazil be brought back in on climate?

There are also ministers within the Bolsonaro government who see how important Brazil’s independent environmental institutions are for the country’s international reputation. Especially the export of agricultural goods and minerals may be affected if Brazilian products are connected to deforestation and environmental crime.

Brazilian agriculture is also threatened by the consequences of climate change. A glimmer of hope for climate activists and environmentalists is therefore that domestic and international actors manage to connect climate change to issues of importance to the Bolsonaro government, such as trade, security and economic growth. Such efforts would require ‘Baptists and Bootlegger’ coalitions between environmental groups in Brazilian civil society and free trade enthusiasts in the government, as well as environmental trade restrictions in importing countries. These coalitions are difficult to establish, and a successful result is by no means given. The future of Brazil’s forests and the achievement of the Paris ambitions are therefore still up in the air.

This blog was written as part of the research project GLOBUS Reconsidering European Contributions to Global Justice (funded by the EU’s Horizon 2020 programme) and first published at the Global Justice Blog www.globus.uio.no.