Hunting moorings in the dark

– fieldwork in the polar night

November at 79 or even 81 N is pretty dark. The sun has disappeared for winter a long time ago, and all that is left is a bit of twilight at noon. For the phytoplankton in the sea that means that there is not enough sunlight to grow. For us, out on a research cruise to service instruments that were deployed north of Svalbard and in the Barents Sea last year or the year before, it means that we struggle to see! Most of the day, it is pitch black dark, especially if it’s new moon as at the start of our cruise. The ship itself is lit up like a Christmas tree with lots of light especially on the work deck in the aft, which often makes seeing anything out at sea very difficult. Light on the bridge is therefore always dimmed and only red light is used when needing a bit more illumination.

Finding our instruments

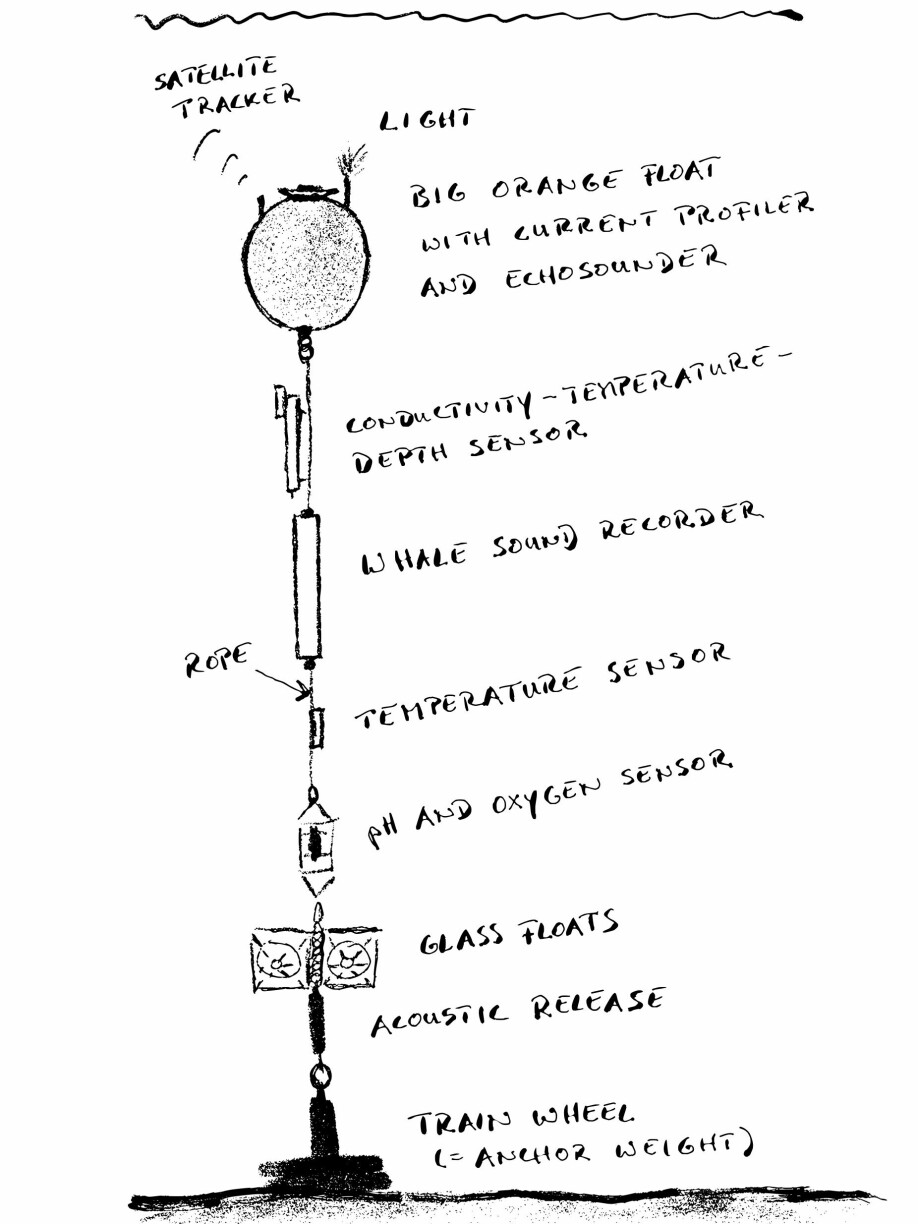

Some people hunt trolls, others tornadoes, we hunt moorings! A mooring is an installation under water which usually stretches from an anchor (i.e. something heavy like an old train wheel) on the sea floor upward with a rope held up by floats. The rope is fastened to the anchor with an acoustic release that we can communicate with. Along the rope, different instruments and sensor are mounted so that we get data at different depths. When we deployed the moorings, we noted down their position so that now, we can go back and take them up again.

In polar regions, the topmost float is well below the sea surface to make sure that the mooring does not get caught by sea ice or icebergs. Therefore, they cannot send their data back to us via satellite, and we have to get them out of the water to read out what they measured over the past year or two.

To communicate with the mooring, we send an acoustic ping to the release at the bottom. When the release gets the correct code and signal, it lets go of the anchor, and the floats pull the entire rope with all the instruments on to the surface. Because of the ocean currents, we cannot be 100% certain where the mooring will come up, and when it’s at the surface, it can quickly drift away with the wind and the sea ice! We therefore check the shipboard current profile to check where the currents are going and look at sea ice drift if there is any sea ice around.

The darkness makes fining them just that bit trickier… So when it’s time for release, it’s all people on the bridge to look out for the floats, full light on the sea from the ship’s beams, and fingers crossed!

Look at that growth!

Even in the cold Arctic Ocean, there’s a lot of life and growth. When we come to recover our instruments after they have been in the water for a year or more, they sometimes look like a monster from the deep sea! When they stand close to the sea surface where light can reach during spring and summer, the instruments become covered by algae, slime, and various organisms – they almost look like aliens. Even though we are quite far north in the Arctic, where the water is only a few degrees above zero in the summer, there is an enormous biodiversity and a lot of biological activity. This forms an important part of the global eco- and climate system.

Happy hunters

After an intense week and a half at sea, we are on the way back to Tromsø. The aftdeck is now covered in floats from recovered moorings and the cargo rooms are filled with the instruments we got back out of the water. Thanks to the capabilities of our research vessel FF Kronprins Haakon and excellent people on the bridge, on deck, in the engine room and, not the least, in the galley, we managed to do our work in the dark and sea ice-covered Arctic. There have been ups – we found many of our moorings! – there have been lows – we lost some moorings – and what we achieved during this cruise will help use to understand better how the Barents Sea and the Arctic Ocean function and change. Time to leave the boat and explore the new data instead!