Right Now!

Lega East? A close look at AfD’s electoral strength in eastern Germany

The electoral showing of Alternative für Deutschland (AfD, Alternative for Germany) at past Sunday’s general election in Germany highlights once again that it is essential to scrutinize the party’s strength in eastern Germany, writes C-REX Postdoctoral Fellow Manès Weisskircher.

On September 26th, Alternative für Deutschland (AfD, Alternative for Germany) entered the German Bundestag for the second time, achieving 10.3 percent of the vote. Compared to its national breakthrough in 2017, the party lost 2.3 percentage points. Over the past four years, the party failed to reach out beyond its core base. Still, its support is relatively stable, given that this time AfD could not benefit from the high salience of immigration and has also suffered from strong and highly visible intra-party divisions, also because of disagreements over how to respond to the Covid-19 pandemic.

As is well-known by now, the party is much stronger in eastern Germany, the former territory of the German Democratic Republic, than in the west. In western Germany, the party gained only 8.2 percent (-2.5). In eastern Germany, however, with a result more than twice as high (20.5 percent, -1.4), AfD stayed the second strongest party. In a recent article in The Political Quarterly, I link the strength of AfD in eastern Germany to widespread sentiments of societal marginalisation. Surveys show that a majority (!) of all eastern Germans, and even more so AfD voters, feel they are second-class citizens. Structural differences related to both the heritage of the German Democratic Republic, and developments since the 1990s, create conditions conducive to AfD's electoral success. In particular, anti-immigration attitudes are stronger in the east, and economic insecurity is higher. Anti-establishment attitudes, along with dissatisfaction with the representation of eastern Germans in politics and society, are also widespread.

Strong only in south of eastern Germany?

Some observers have emphasized that AfD is not mainly popular in ‘the east’ in general, but in the south of eastern Germany, and there especially in the countryside and less in cities such as Leipzig and Jena. And indeed, a closer look at the election results reveals variation in AfD strength across the east. In the states of Saxony (24.6%, -2.4) and Thuringia (24%, +1.3%), AfD even became the largest party – cases of symbolic success. Thuringia was the only region where the party could actually gain voting shares – even though the state secret service considers the regional branch there as ‘extremist’. In both states the party benefited less from its own gains and more from the struggling center-right CDU, which lost heavily. In Saxony-Anhalt, AfD obtained 19.6 percent, the same voting share as in 2017, ending up behind SPD and CDU.

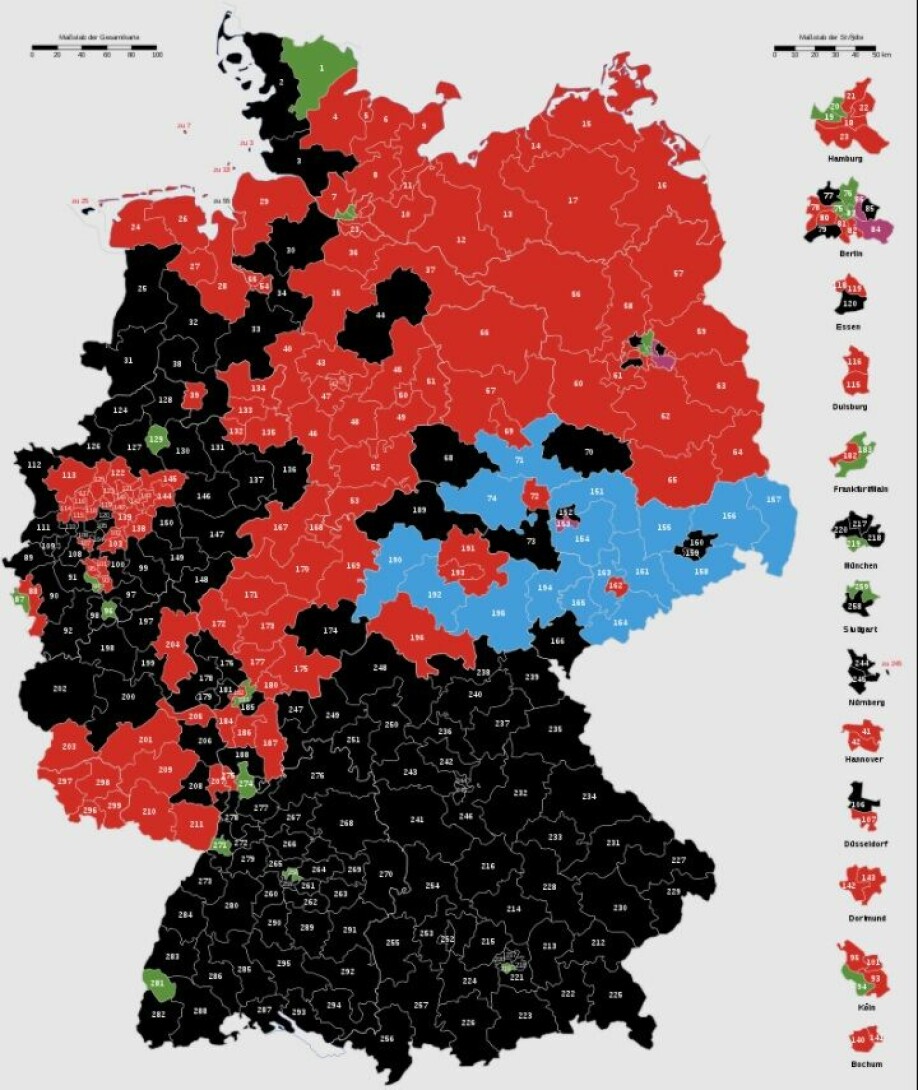

Eastern Germany’s southern states of Saxony (10) and Thuringia (4) and the south of Saxony-Anhalt (2) are also the regions where AfD won its 16 Direktmandate, with candidates directly elected to the Bundestag through relative majorities in electoral districts (see Figure 1) – and not through the lists of their state party branches. AfD benefited again from fragmentation and the struggling CDU here. But many direct candidates also gained support. Most prominently, party co-leader Tino Chrupalla, who ran in the Saxon electoral district of Görlitz, the most eastern town of Germany, achieved 35,8 percent of support (+3.4). In comparison to AfD’s 16 Direktmandate, Die Linke, formerly a regional power in the east, merely won three electoral districts.

In Brandenburg and Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, states in the north of eastern Germany, AfD did not win any Direktmandate. Still, it is important to emphasize that the party is also much stronger in Brandenburg (18.1%) and Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (18%) than in western Germany, ending up second in both regions, only way behind SPD. AfD is indeed electorally strongest in the south of eastern Germany, but it is also substantially stronger in the north-east than in western Germany.

Interestingly, some party figures emphasized that AfD could have won even more electoral districts had it not been for the new party dieBasis, a fringe extremist party of lockdown-critics and corona skeptics, which is blamed for having stolen a percent of support or so from AfD in some narrow constituencies in the east. At the same time, other AfD figures were also internally dissatisfied with a side effect of achieving so many seats through Direktmandate. Germany’s electoral laws aim at proportional representation. If candidates of a party win disproportionally more directly elected seats through the ‘first vote’ than the party itself receives ‘second votes’, the party receives less seats through its regional lists. This is why some prominent candidates on state lists, especially in Saxony, did not make it into parliament. For example, former judge Jens Maier, among the furthest to the right of the party and guest speaker at PEGIDA, failed to win his electoral district in Dresden. And even though he was second on the AfD’s regional list in Saxony, the many Direktmandate obtained in Saxony prevented him from reentering the German Bundestag.

A delicate balance of power

The stark electoral differences between the west and the east fuel internal conflict. Party co-leader Jörg Meuthen, Member of the European Parliament, and a neoliberal from the west, warns of a ‘Lega Ost’. Stefan Möller, co-party leader in Thuringia, emphasizes that AfD should learn from the east. There, some AfD politicians criticize the weak electoral results in the west. Many in the west, however, blame a radicalizing AfD in the east and its cooperation with the ‘corona-skeptics’ of the Querdenken movement for the lack of electoral appeal.

These different perspectives relate to long-term intra-party divisions. Inside AfD, influence of the neoliberal ‘moderate’ party founders has been waning. These moderates have been mainly dominant in the west, where limited electoral success weakens their role inside the party – also inside their western branches. Forces mainly dominant in the east – with a stronger focus on welfare expansion for German citizens only, and a higher inclination to cooperate with far-right street movements and anti-lockdown protestors – have become increasingly influential.

However, given the much larger population of western Germany in comparison to eastern Germany, AfD’s new parliamentary group – and membership – consists of far more westerners: 51 of AfD MPs were elected in the west, and only 29 in the east (Berlin excluded).

Broader implications of AfD’s strength in the east

Beyond internal developments, AfD’s strength in the east is also important for the future of mainstream politics in Germany. In the eastern regions, mainstream parties increasingly opt for three-party coalitions to find majorities, rejecting cooperation with AfD. In some cases, such as in Saxony and Saxony-Anhalt, quite conservative CDU branches cooperate(d) with the social democrats and the Greens. These constellations cause dismay among a minority of CDU figures sympathetic to the thought of cooperation with AfD.

Currently, however, regional AfD politicians I interview for the MAM project do not expect coalition opportunities soon. Whether the center right will be able to resist the temptation in the medium term also depends on the consequences of Sunday’s election: a potential loss of the chancellorship may cause an internal reshuffle, weakening those that most strongly oppose cooperation with AfD.

This is an updated version of an article on AfD’s situation ahead of the election on ECPR’s Political Science blog the Loop.