Another brick in the wall: Covid-19 and the crisis of the liberal order

Covid-19 risks being another hit to the liberal world order, argues GLOBUS researcher Sonia Lucarelli.

When the first cases of infection by Covid-19 were discovered in Italy, in late February 2020, my book on the crisis of the liberal order has just appeared on library shelves. At first glance I thought that I had been too pessimistic in my book and that the new virus could be able to transform the international landscape to the better.

In a few weeks Italians were in strict lockdown all over the country, caught by surprise, fear, anxiety, but also by an unprecedented faith in science and even trust in the leading political and technical elites. Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte and the Head of 'Protezione civile' Angelo Borrelli appeared on TV as new oracles. Scientists and medical staff become the national heroes, and rally around the flag prevailed over traditional political divisions. Populism, which has been strong in Italian politics in the past few years, seemed to be a distant memory. Never before had the World Health Organization (WHO) been more present in the news and more appreciated by the wide public.

Similar scenes have appeared in other countries, suspending for a short while the chronic crisis of trust in 'the establishment' (experts, politicians, domestic and international institutions). This decline of trust has severely damaged the functioning of liberal democracy and of international liberal institutions in the past few years. For a moment it seemed as if the shared vulnerability of all human beings had made clear that we have no alternative but an enhanced global governance and international cooperation.

Yet, the multilateral momentum seems to have passed and pre-existent trends challenging the liberal order have reappeared. In particular, an order made of liberal democracies, international multilateral institutions, global norms and high connectivity, cannot survive without lively liberal societies in the background.

Indeed, the greatest challenges to the perpetuation of the liberal order are not represented by rising non liberal powers such as China, but by the crisis of liberalism 'at home'. Covid-19 risks being another hit to the resistance of the liberal project.

Bye bye faith in progress and trust?

The liberal tradition, from its eighteen century founding fathers onwards, has been grounded on a progressive view of history, in which progress is human-made through knowledge, science and technology and hard work. Progress is regarded as a public good potentially benefitting all human beings.

The historical manifestations of the liberal order in its various forms (post World War I, post World War II, post-Cold War) have been guided by political and socio-economic engineering aimed at creating conditions for a more wealthy and peaceful society. Liberal economy is ontologically grounded in the need of an ever-expanding economy and liberal societies have anchored their equilibria on the existence of a generational social lift.

Trust is another fundamental requirement of a lasting order. In the case of the liberal order, trust is a conditio sine qua non (without which there is nothing) for functioning institutions.

However, faith in progress has been hit by the inability of liberal institutions to deliver more wealth and more peace. Trust in scientific, technical and political competence and institutions have been further negatively affected by the disintermediation provided by the digital revolution, which allowed for forms of decoupling between knowledge and power.

At first sight it seems that the pandemic has brought the importance of scientific competences to the attention of the public. Yet it is too early to claim victory of science and competence in politics, for two reasons.

Our societies lack the ability to cope with the fact that science is not certainty, but rather trial and error.

First, because our societies lack the ability to cope with the fact that science is not certainty, but rather trial and error. If following a moment of disconcert people gave credit to scientists, they expected clear-cut answers that Covid-19 researchers could not provide, leaving space to alternative voices and fake news.

Second, Covid-19 has illustrated the clash between the perception of time that different stakeholders pertain. The time of economy clashed markedly with the time of the epidemics. Donald Trump’s listening to the cautious words of Dr. Anthony Fauci has soon left place to anti-scientific declarations. Science and economy have clashed more than ever and a possible revamp of the virus in the autumn would put economic and health imperatives even more at strain. Should this happen, there is a risk of a new round of delegitimation of expertise.

De-globalisation and populism

Covid-19 has brought new arguments to the critics of globalisation, and particularly of what has been labelled 'neoliberal' globalisation.

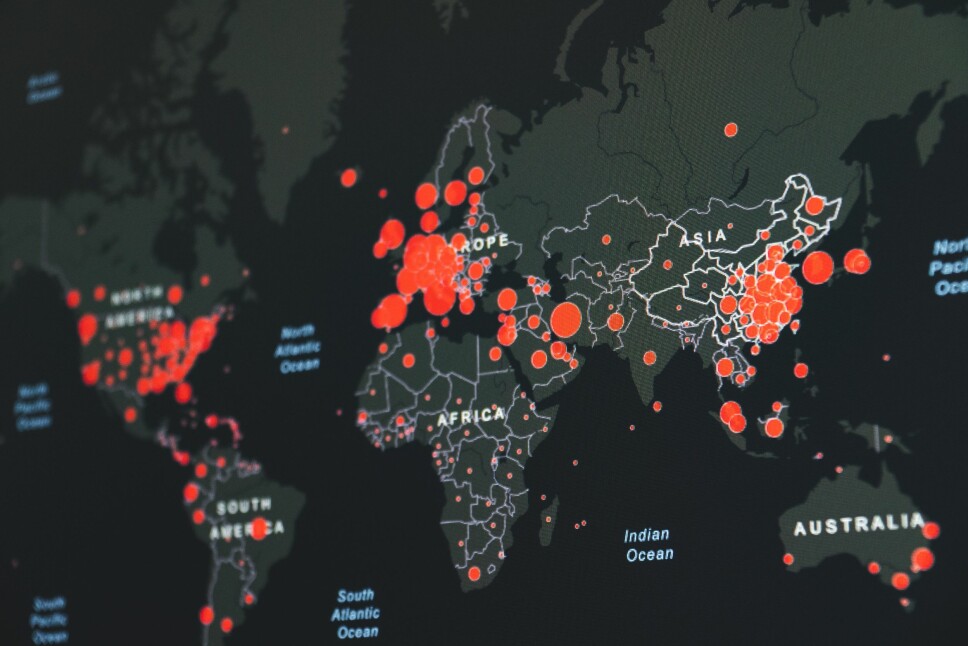

The spread of the pandemic in the range of a few months would have been unthinkable without a high level of human and goods mobility. Some of the shortcomings of globalisation have been made more visible. The global division of labor and long production chains revealed the vulnerability of developed societies, for instance because they have proved unable to cover their need of basic health protections tools such as masks and gloves in cases of emergency.

The inequalities spurred by our digitalized economy are now made even more visible by the uneven impact of the new virus. In the United States and the UK, where the social safety net is weak, the virus hits harder among marginalized groups, provoking more contagions and deaths and more serious economic consequences.

The lesson-learned is that societies with a stronger welfare state that guarantees state health provisions and social insurances are more resilient to challenges like Covid-19.

The lesson-learned is that societies with a stronger welfare state that guarantees state health provisions and social insurances are more resilient to challenges like Covid-19, at least in terms of avoiding inequalities in treatment. Yet, this lesson will hardly be learned. Caught by the negative economic effects of the lockdowns, the losers of Corona will add up to the losers of globalisation, widening the electorate of populist leaders. This is bad news for the multilateral system and for the EU.

Illiberal tendencies

Illiberal tendencies have been registered already some years before Corona.

They are visible in the political agendas of populist right wing movements in Europe, but also in the actual policies of governments in Hungary and Poland, as well as by Donald Trump in the US, let alone by Bolsonaro in Brazil.

With corona, quickly securitized, many governments have adopted emergency measures and procedures, limiting temporarily the involvement of the Parliament. It remains to be seen what may happen in the case of a second wave of Corona or a prolonged emergency.

Manifestations against lockdowns as limitations of personal freedoms have already repeatedly appeared in the US and in Germany, and risk turning into social clashes and occasions for contagion.

Digital pervasiveness

The digital revolution was already challenging the liberal order for many reasons among which its economic impact (delocalization, empowering of digital industry, transformation of the job market), and its impact on the privacy of citizens’ personal information.

The digital revolution has altered the relationship between public and private, as well as the trust in the protection of rights by state institutions. Covid-19 has enhanced the relevance of the digital revolution for our lives, from the sphere of private contacts to that of high politics.

If Corona has shed a positive light in the opportunities provided by digital connectivity (I wonder what it was like staying at home for three months during the Great Plague!), it has also shown how dependent we are on digital tools and how influenced we can be by spoilers of the instrument.

Fake news on Corona have become the new frontier of disinformation, risking to jeopardize cautious communication by the WHO, scientists or states.

The digital economy has profited more than anyone else by the lockdown, and yet we still have not sorted out how to properly tax companies like Amazon and Google.

Moreover, the digital economy has profited more than anyone else by the lockdown, and yet we still have not sorted out how to properly tax companies like Amazon and Google. At the same time, they have gained portions of the market, hence amplifying the post-Corona economic crisis.

No way out?

As liberalism has taught us, socio-political structures are human-made and can be engineered so to better cope with challenges. Covid-19, as any crisis, has consequences that can go in different directions depending on our collective response. The greatest risk is that we overlook the fact that it builds on an already challenged liberal order and might enhance its weaknesses. Effective responses should not run this risk.

After moments of uncertainty, it seems that the EU has understood what is at stake and has responded with substantial economic measures. Yet, the response has been slow with respect to the speed of the effects of Covid-19 and it now needs acceleration and better communication to the European public.

If the economic emergency is not tackled timely, populist backlashes are highly possible.

At the national level, after the health crisis, if the economic emergency is not tackled timely, populist backlashes are highly possible. It is fundamental that the response is made in such a way to compensate possible inequalities of impact of the virus; that bureaucratic barriers (very high in several European countries) do not impede a swift implementation of the adopted measures; and, finally, it is crucial that the renewed national proudness is not be played against external others and emergency measures are removed as soon as possible.

At the international level, it would be time to relaunch a large debate on the enhancement of global governance, and on the reform of international institutions that now risk delegitimation if not dismantlement e.g. the WHO.

The decision of the American electorate, in Autumn 2020, will play an important role in this game.

But, it is also time for the EU to gain a global role and – for instance – relaunch its plan for a more sustainable global economy and work to make sure that the future vaccine for Covid-19 will be treated as public goods to which anyone in the world has access.

———