Blog: Natural Histories

Blog: natURAL HISTORIES

Why are sperm cells so diverse when they all have the exact same job?

Why are sperm cells so diverse in shape, when they all have the same simple task? To solve this mystery museum scientists sample bird sperm from diverse species around the world.

Sperm cells are a bit of a mystery. They have a very simple task—to fuse with the egg and deliver their DNA for the embryo. And yet the shape of sperm cells is exceptionally diverse across species, appearing to break one of biology’s most accepted rules: that form follows function.

So why do sperm, with their single task in all species, come in so many different shapes and sizes? This seemingly simple question has great implications for our understanding of how species evolve and eventually form into new species.

The Sex and Evolution Research Group at the Natural History Museum studies this mystery, focusing on a large group of birds called songbirds. Songbirds make up over half of the world’s ~10,700 bird species and include species like magpies and house sparrows.

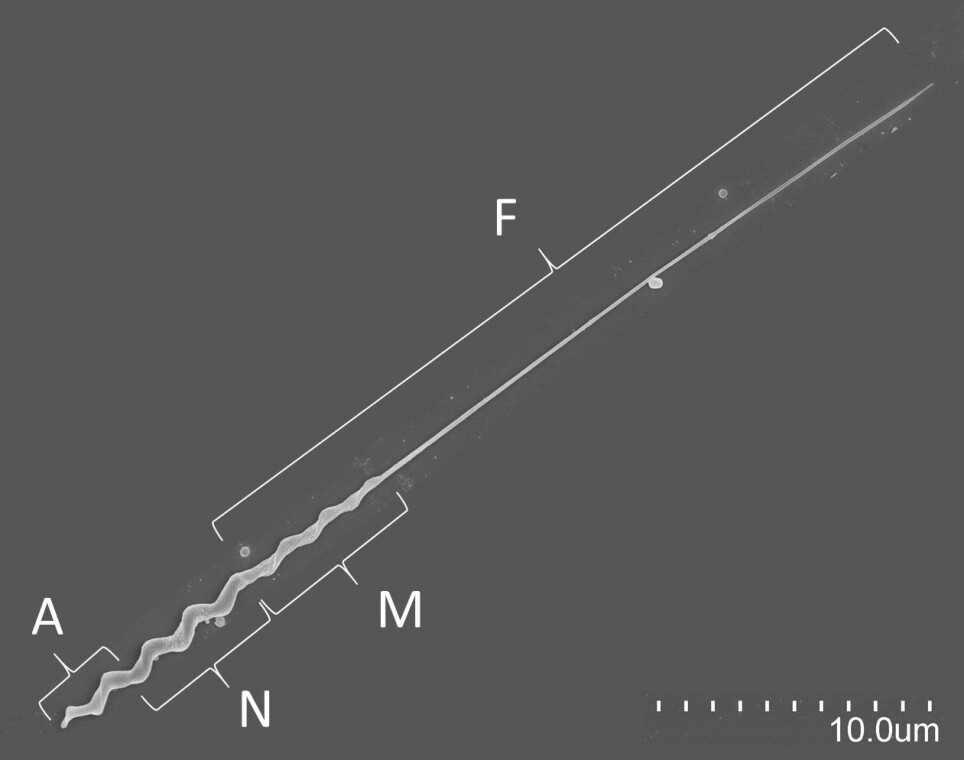

Unlike the typical mammalian tadpole-shaped sperm cell, songbird sperm is shaped more like a drill bit or a screw. That is, they are long and slender with helical structures along most of the length of the cell, and they spin around their longitudinal axis as they swim.

We’re particularly interested in understanding how these cells diversify and evolve, which in turn requires us to examine the size and shape (that is, morphology) of many species’ cells.

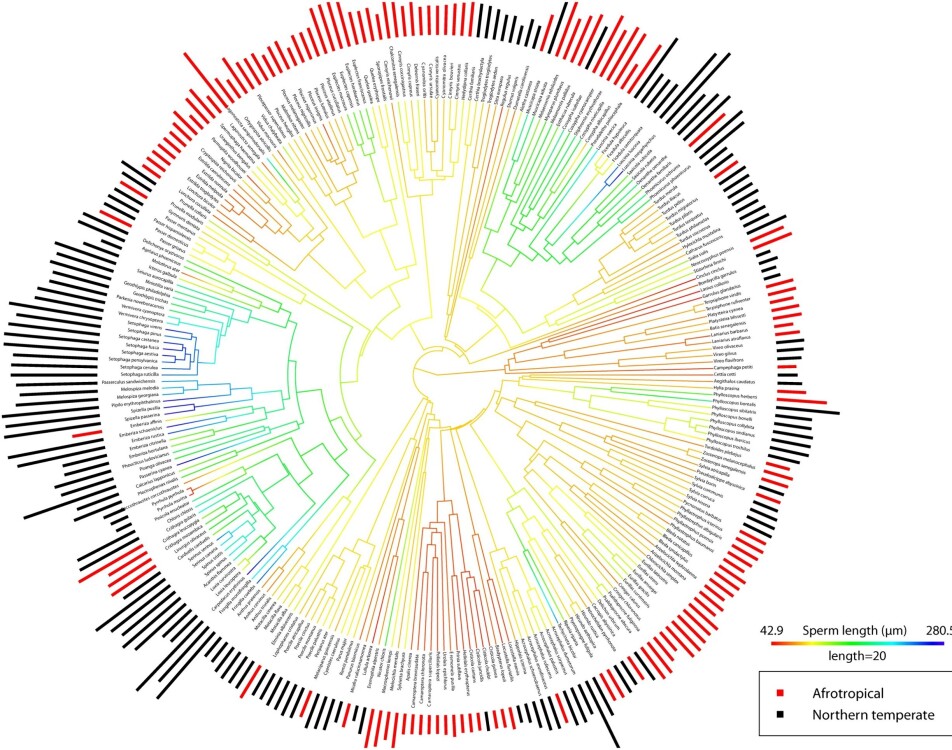

Our lab has shown that sperm length is more similar among males in the species where more males’ sperm compete to fertilize the same set of eggs.

This pattern suggests that having an optimal sperm length is more important in these species. When we map cell morphology onto the phylogenetic tree—the evolutionary relationship among species—we see that morphology diversifies more quickly in some groups than others, which might indicate stronger selection in those species.

We can then also test whether sperm characteristics relate to how rapidly new species form within a group. This is a reasonable hypothesis if sperm are less effective at interacting with other species’ female reproductive tracts or eggs.

A somewhat daunting – but also exciting! – task, then, is to collect sperm samples from across the songbird phylogeny. We previously have sampled many of the species living in Europe, eastern North America, western and southern Africa, and southeast Asia, but many habitats and regions of the world remain to be sampled.

This year, our group has conducted several field expeditions, with local collaborators, to collect sperm from new species. We use a sperm collection technique that does not harm these small creatures .

In May, we went to western North America, more specifically California. Here we took samples from many species that are closely related to eastern North American species that are already in the Natural History Museum’s Bird Sperm Collection, which is the world’s largest such collection.

We conducted this fieldwork in oak-savannah habitats as well as mountain meadows—a rewarding experience on a personal level, as well as scientifically! We have also just returned from an expedition to New Zealand, where we sampled invasive European species to examine evolution on a very short time scale.

With the samples now fully accessioned to the NHM Avian Sperm Collection, we are beginning to measure the sperm cells. We hope these analyses will reveal more of the secrets of sperm cells, and how these mysterious cells have influenced the incredible biodiversity around us.

FURTHER READING: