Blog: Natural Histories

Blog: natURAL HISTORIES

Nature's strangest collaboration

Evolution talking, the greatest concern of all life is to leave behind successful offspring. Species must band together to ensure future generations. The fig and the fig wasp are the perfect example.

Should you find yourself strolling along the roadside of the Italian countryside and happen to pick a sun-ripened fig, you might find a small insect inside. A little wasp, now dead, and completely black, no bigger than a grain of rice. Did the wasp end up in the fig tree to eat its fill? No, it was there to complete an entirely different task.

The fig flower

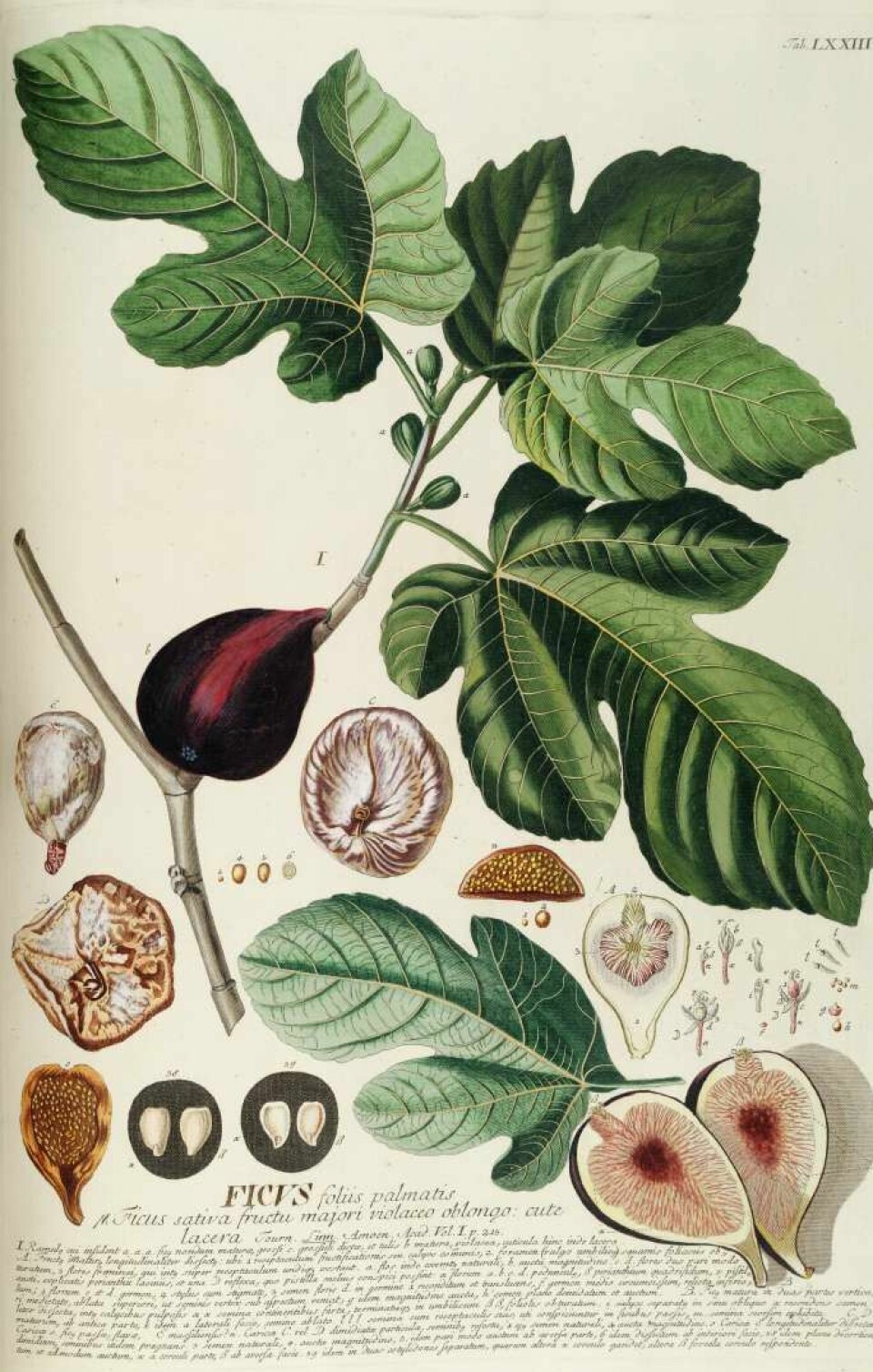

Unlike other fruits, the fig is not a fruit at all. You may have heard that a banana is a berry, and that a walnut is not a nut but a stone fruit, or that a raspberry is several small stone fruits put together. The fig is neither a berry, a nut, nor a stone fruit. It is an inside out flower.

Pollen is the start of the next generation

Most flowers open their buds to reveal their waving stamens, not the fig. The fig is a flower that closes more and more inward, until everything that was supposed to point out, now points in. Flowers open for a reason; in hope an insect will across their stamens, take its fine pollen to a neighboring flower, for fertilization. For the transport of pollen, the flowers need help.

The fig and the wasp

We could agree, the fig has made this process quite difficult for itself. The fig hides its flower from everything and everyone who buzzes past. Except for the one insect that gets the job done, the fig wasp. When a female wasp lands on a fig, she crawls into an almost invisible opening at the far end of the fig. In two small recesses on her back, she carries the pollen from another fig. At the opening, she begins to push her way in and on through a narrow passage with hooks on the wall.

Every step she takes forward becomes impossible to go back. It is too cramped, her antennae bend, and her wings now folded start to tear. Finally, she is at the end of her journey, the pollen she carries lands on the tightly wrapped flowers and fertilizes them. She is badly injured, and completely trapped, but she has one last job: She lays her eggs in some of the tiny flowers, before she lays down to die.

A new generation of figs and fig wasps has begun

The fig pays a price to shelter the wasp’s young. The flowers where the eggs now lay do not become seeds that produce a new fig tree. When the eggs hatch, the small insects eat their fill of the developing seed around them. The male wasps hatch first. They climb out of each little flower and fertilize their sisters.

After the main task performed by the male is complete, they dig tiny tunnels out of the fig before it is time for them to die. When the female larvae hatch, they climb out of their flowers. Taking the pollen now stuck to the recesses on their back, they crawl out of the tunnels prepared for them. They fly off to look for a fig to entre and lay their eggs, spreading the pollen as they go. What happens to the dead wasp entombed in the fig? Do we eat it along with the dried figs at Christmas? No, not necessarily. The fig breaks down and eats the dead wasp body.

Through this whimsical yet majestic cooperation, both the fig and the wasp suffer. The wasp pays with its life and the fig sacrifice some of its potential offspring, but together they take care of the greater goal, and provide for their next generation.