The Black Death came to Europe at different times

Scientists have long believed that Europe was hit by successive waves of plague because the disease survived on the continent in rats and other rodents. But new research suggests instead that the plague came multiple times along trade routes from the East.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

In 1347, a number of ships sailed into Italian ports with a terrible cargo. It was a cargo that would affect nearly everyone in Europe: the plague.

Over the next few years, the Black Death travelled like wildfire through the European population. It arrived in Scandinavia in 1349 before it swept further into Russia.

A significant percentage of the populations of many countries were dead by the time the dreadful pandemic finally burned out. But the nightmare was not over yet.

During the course of the next four centuries, the plague returned time and again, in epidemics great and small in different areas of Europe. The last outbreak occurred as late as the 1800s.

Was thought to survive in rodents

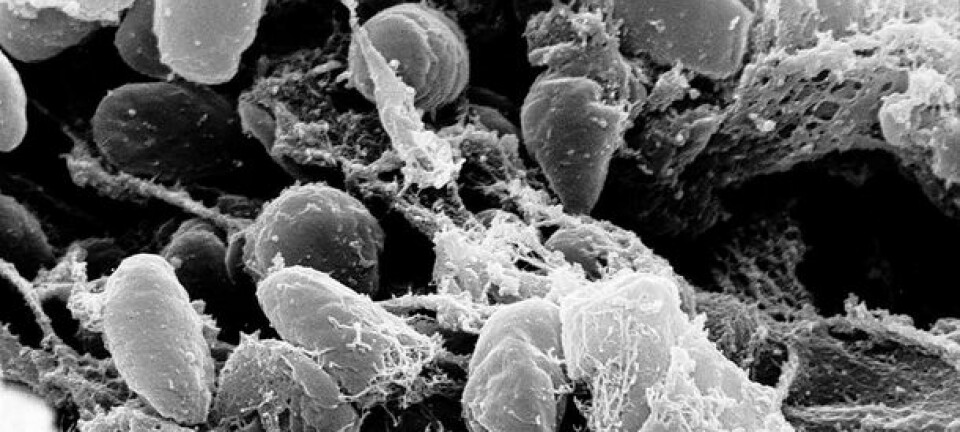

Scientists have long believed that the plague bacterium, Yersinia pestis survived in Europe’s wild rodents between the different outbreaks.

But now a team of Norwegian and European scientists has found no evidence that the plague was harboured by rodent populations in Europe between outbreaks.

Instead, the bacterium was most likely reimported from Asia multiple times, the researchers said.

“I am very surprised by the results. I initially thought that these kind of plague reservoirs were found in European rodents,” said Professor Nils Chr. Stenseth, head of the Centre for Ecological and Evolutionary Synthesis (CEES) at the Department of Biosciences, University of Oslo, and one of the researchers behind the new results.

I am convinced that the plague must have come in several waves. If we find out that this is true, then it explains many other different things.

“But this explains why there are no longer outbreaks of plague in Europe, unlike elsewhere in the world,” he said.

Climate affects the plague

There is still plague out there, however. Today the bacterium is found in gerbils and other wild rodents in Asia, Africa and America. The disease occasionally infects humans who come into contact with the animals that carry the bacterium. Stenseth and his colleagues have spent much of the last decade studying how and why this suddenly happens.

They have found that climate makes a big difference in determining the circumstances of an outbreak. When the spring is warmer and the summer wetter than usual, gerbils have access to lots of food and can live well. That increases both the number of animals and number of fleas quickly. This kind of increase can take place over an entire region.

If some of these animals carry the plague bacterium, it can then spread to many more animals and over larger areas.

But when the climate changes and times get tough, many gerbils and other wild rodents die. Fleas then tend to flock in large quantities to animals that are still alive. And although fleas prefer to live on rodents, it happens that the remaining animals are so thickly infested that the insects begin to search for alternative hosts – like humans and their livestock.

That increases the risk that a plague-infected flea will bite a human, and thus transmit the plague bacterium to us.

Historical descriptions of plague a key

Previous studies of climate, rodents and fleas thus gave scientists reason to assume that the complex connections between climate and pests in Europe was the cause for the recurrent plague epidemics after the Black Death.

Stenseth, Boris Schmid and Lars Walløe from the University of Oslo and their European colleagues decided to test this hypothesis.

“We took historical data over time and place for plague outbreaks after the Black Death and asked: Is there a connection between climate in Europe and the timing of new epidemics?” Stenseth said.

The scientists went through 7711 historical descriptions of plague outbreaks, and compared them with analyses of annual tree rings from the same dates and locations. This comparison allowed them to see if sudden outbreaks of plague among humans followed specific changes in climate.

“But we found no evidence for this in Europe,” Stenseth said.

The researchers did find another link, however.

Started in Asia

“When we analysed climate data from Central Asia, we found a clear correlation between climates in Central Asia that would promote plague and the occurrence of plague in Europe 12 to 15 years later,” says Stenseth.

This suggests that the plague bacterium was found in different rodents in Asia, and then – when the climate allowed – could spread to domestic animals and people, which over time carried the disease with them to Europe.

There were also hints that this was the case in the annals of history. In many cases where there were sudden outbreaks of plague in Europe, the outbreaks would start in a seaport on the Mediterranean or Black Sea.

These were the harbours where goods from the Silk Road and other trade routes from the east were shipped.

Next: old teeth

Perhaps new waves of plague travelled to Europe with camel caravans from the East, the researchers suggest in the article, which has now been published in PNAS, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States.

Many of these trade routes travelled through areas where wild rodents are now known to carry plague. And scientists already know that it is very easy for camels to be infected by plague fleas in these areas, which in turn allows them to transmit the disease to humans.

“But we do not yet know whether or not new plague epidemics actually travel this way,” says Stenseth.

He says that the next step is to use genetic material to determine whether the idea is correct.

The researchers will examine plague DNA that has been preserved in the teeth of people who are known have died of plague at different times and places.

If there really were different varieties of plague that came from Asia in several waves, scientists expect there to be relatively large genetic differences between the plague DNA preserved in the teeth from different dates. If all of the outbreaks have their source in the same bacterium that came in 1347, there will be much less variation.

Stenseth believes this kind of DNA analysis will provide a fairly definitive answer.

“I am convinced that the plague must have come in several waves. If we find out that this is true, then it explains many other different things,” he said. “And if this is true, the history of the Black Death and the subsequent plague outbreaks will have to be rewritten.”

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk