Growth rings from the days of the Black Death

A piece of wood from a storehouse in Norway reflects back to a story of a young girl who survived the bubonic plague and details climate conditions and construction methods in the 1300s.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

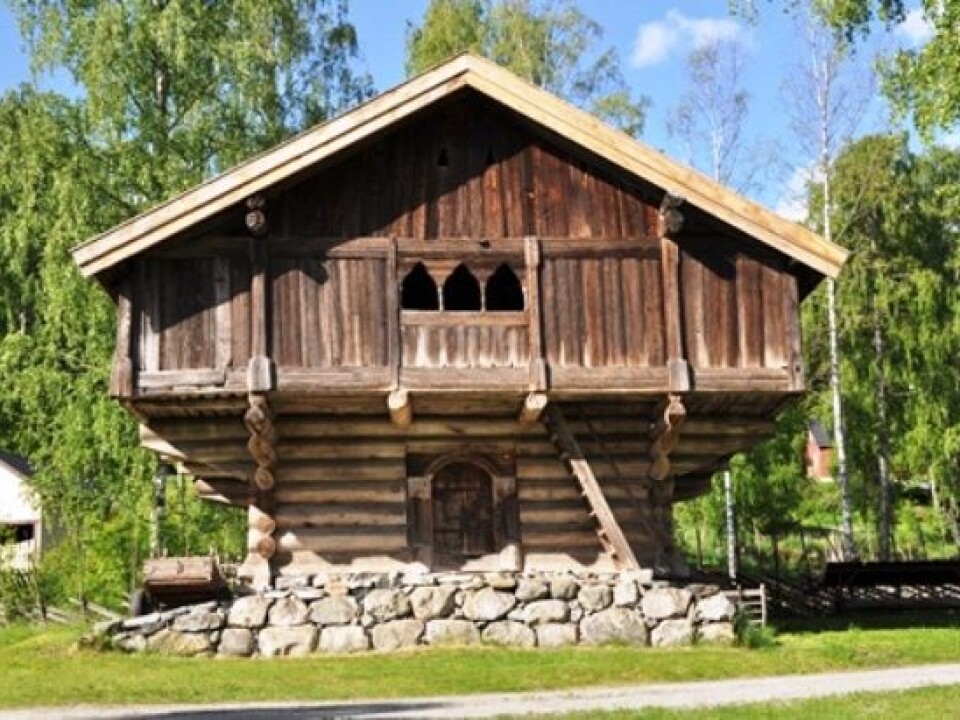

According to folklore from the valley Hallingdal, between Oslo and Bergen, a young girl was locked into a farm storehouse to protect her from the Black Death.

The pandemic killed tens of millions in Asia, Europe and Africa and wiped out half of Norway’s population in the mid-1300s.

The owner of the Stave Farm understood the danger when people in his rural valley started dying of the bubonic plague.

He reasoned that the disease would strike his family too, so he sequestered his daughter in the safest and sturdiest building on the farm, the storehouse, and locked her in alone.

According to legend, the girl in the storehouse heard it getting quieter day by day on the farm. Fewer voices were heard. After a while there were none.

Few secular buildings from the 1300s

The famous Stave Farm storehouse is the favourite building of Associate Professor Terje Thun at the Museum of Natural History and Archaeology in Trondheim, who has dated a thousand Norwegian buildings.

“Norway is the richest country in the world when it comes to the number of old log buildings from the Middle Ages, but only a few buildings from the time of the Black Death are still with us,” he says.

Few buildings have been dated to the middle and late 1300s because little construction was carried out. The Black Death was devastating in Norway, also economically, and empty farms were common.

So Thun was particularly delighted when he dated the Stave storehouse to exactly 1334, just a few years before the onslaught of the Black Death.

Growth rings show the exact date

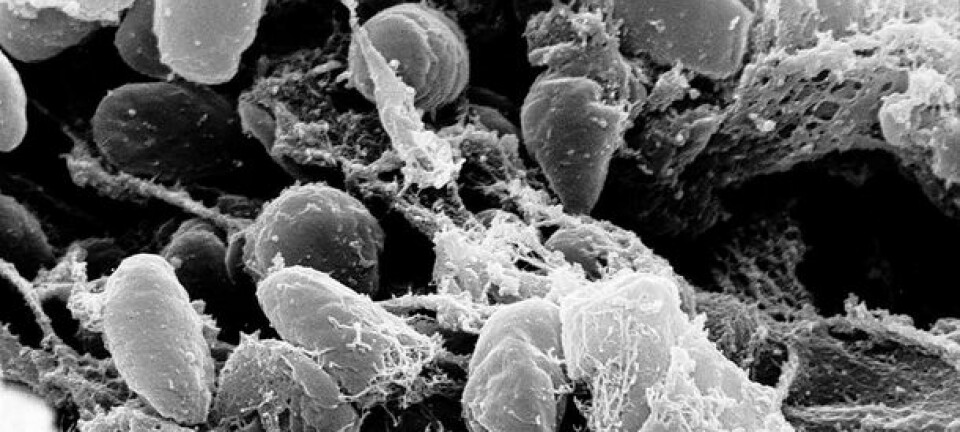

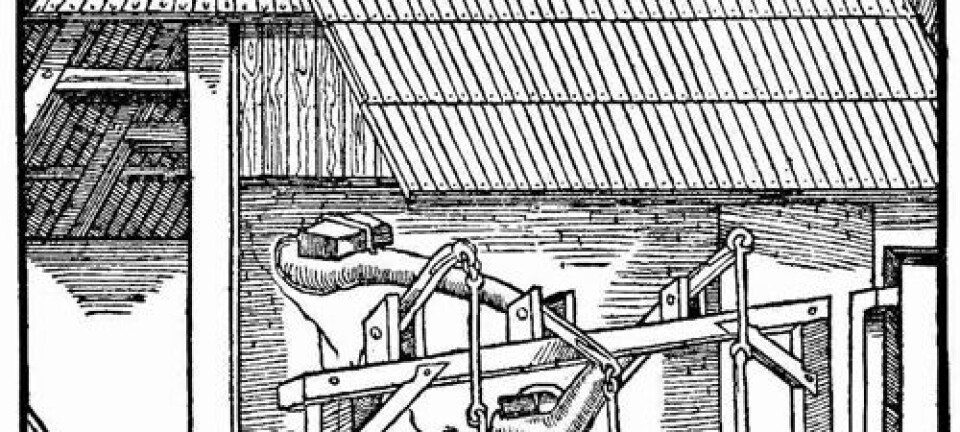

Thun compared the growth rings in the wood from the Stave storehouse to the historic record for the region. The method is called dendrochronology – from the Greek words for trees and time.

The dimension of growth rings, or annual rings, in trees differs from year to year.

A warm, wet summer will promote growth and the ring from that year will be large. In cooler the rings will be tighter together.

Over the years the combination of good and bad years for a tree will create a unique sequence, something like a barcode.

“Each year sets its fingerprint on the trees,” says Thun.

The growth rings are counted and compared to a growth ring chronology − a reference series − stretching far back in time. Undated samples of wood can be matched with the annual ring chronology.

The exact year a tree was felled can be determined if the growth rings are clear and sufficiently representative to tally against known annual growth records.

Also used for climate dating

It works both ways. Growth rings in trees can also be used to determine the climate at given dates.

Helene Løvstrand Svarvas, a research fellow at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, secures information about temperatures, precipitation and place of growth by studying the pattern of these annual growth rings.

“The fun thing about dating is that we try to continuously stretch further back in time,” says Svarvas.

Sole survivor at Stave Farm

Nobody knows how long the girl was locked inside the Stave storehouse. But according to legend she was found by people passing by who heard her and understood that there was a survivor on the farm.

The storehouse was moved from the Stave farm in Ål to the Halingdal Museum in Nesbyen in 1908, where it has now stood the last 100 years.

It is the oldest building at the museum and the oldest secular building in Hallingdal.

Translated by: Glenn Ostling