Live normally despite a hole in heart

Children born with a hole in the wall between heart chambers are often viewed as sickly or feeble. But a new study shows that kids with this relatively common congenital heart defect are just as healthy as other children. A researcher claims we are doing them a disservice by pathologising them.

Some 9,000 children under 18 in Norway (population 5 million) have congenital heart defects. One in every hundred children is diagnosed with such problems at birth. The most common defect is a hole in the septum – the wall between the heart chambers.

Only a marginal number of these children have holes that require surgery. Most of them get by with regular check-ups.

A new Norwegian study indicates that many of these children with smaller, uncomplicated heart defects don’t even need to be medically checked up so regularly.

No need to be considered sickly

“Most of the children with a hole in the heart are needlessly viewed as sickly and stigmatized as ‘heart children’. But this is doing them a disservice,” says Jarle Jortveit, a chief physician and medical researcher at Sørlandet Hospital in Arendal, Norway.

He is the first author of a study which has drawn a positive as well as critical response from a paediatric heart specialist at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU).

Same mortality rate

The study shows that children with holes in the septum (the wall between the main pumping chambers of the heart) have no excess mortality and few of them develop complications or require special treatment.

“We hope the findings can help give reassurance to a large number of children and parents. Most of the children do not need to restrain any of their daily activities,” says Jortveit.

The study entailed over 943,000 children born in the 16-year period of 1994 to 2009. The researchers used diagnostic data from Norwegian hospitals and the Medical Birth Registry of Norway.

The study has been published in the Archives of Disease in Childhood and covers the largest cohort to date with this heart defect.

Congenital heart defects

Doctors and midwives routinely use stethoscopes to listen to the hearts of all new-borns. If they hear anything out of the ordinary the babies are examined further.

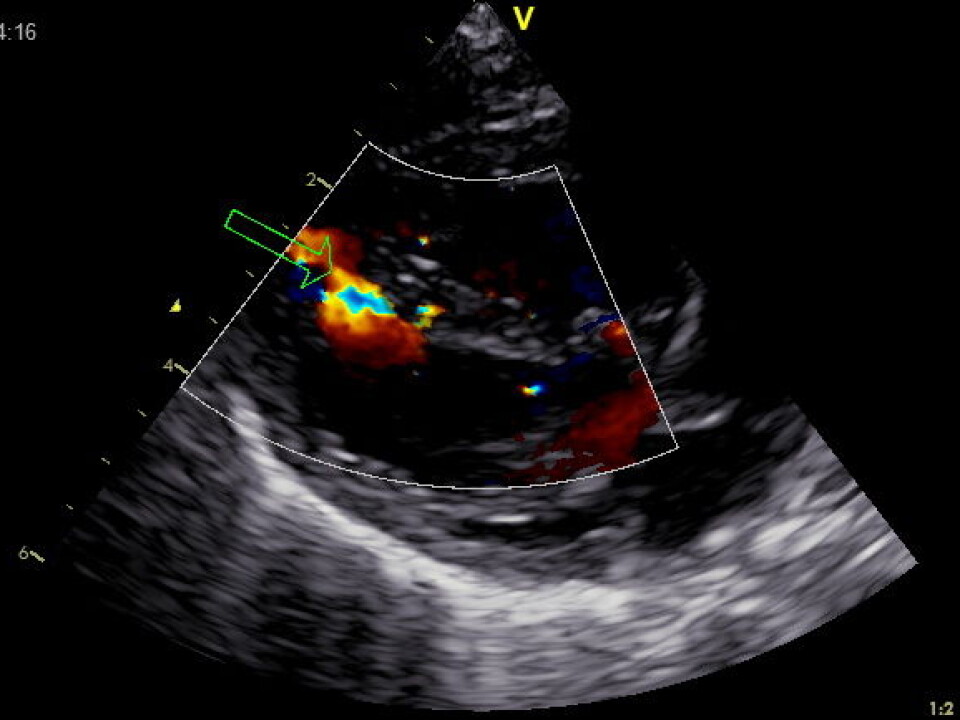

Congenital heart defects are the most common birth defects found. A hole in the septum which separates heart chambers, a ventricular septal defect, or VSD, is the most frequent type of these defects.

The gravity and complexity of such heart defects vary greatly. Holes in the septum can occur in combination with other heart defects or diseases. In certain cases the holes are serious enough to warrant surgery and follow-up examinations.

In the new study the researchers paid a closer look at 3,495 children with isolated VSDs, in other words without other cardiac malformations or chromosomal aberrations.

Size and position

Only 181 of these children required surgery.

“The need for surgery depends on the size of the hole and its position,” explains Jortveit.

He thinks that improved diagnostics in the past years have had an unintended side-effect.

“We find more holes than we used to. As a result, more children are deemed to be infirm and in need of check-ups. This impinges on the children’s and parents’ quality of life,” he asserts.

Diagnostics and communication

A chief physician and paediatric cardiologist, Siri Ann Nyrnes at the Children’s Clinic of St. Olavs Hospital and NTNU, disagrees with the claim that enhanced diagnostic procedures entail such drawbacks.

“There is no reason to problematize a more frequent discovery of holes thanks to improved diagnostics. Better imaging is essential because it helps us in seeing which children require surgery and further follow-ups and which children who can get by without it,” writes Nyrnes in an e-mail to our Norwegian affiliate forskning.no.

The size and position of the hole in the heart must be charted for such decisions to be made.

“But it is the doctor’s task to be clear in their communication with the parents about which holes are small and inconsequential and have no impact on the child’s quality of life and life expectancy,” writes Nyrnes.

No higher mortality rate

The children who received treatment had their VSDs closed through surgical or catheter-based treatment. No children died in connection with these surgical procedures, nor were there any complications requiring hospital treatment.

The researchers compared the mortality of children with VSDs to that of all other children born in Norway the same year. There were no differences in mortality between kids with the congenital heart defect and their peers with normal hearts.

“This shows that we have good routines for detecting which children need such operations and which do not,” says Chief Physician Henrik Holmstrøm, who was responsible for the study. He follows up children with VSDs and their parents as part of his job at Oslo University Hospital, Rikshospitalet.

Not such a bad condition

Many of the other children who did not require surgery are rigorously followed up for years with ultrasound examinations conducted by cardiologists.

The researchers behind the recent study think that such procedures can be unnecessary and they tend to pathologise the kids.

“The study shows that the risk linked to the most common congenital heart defect is very minor,” says Jortveit.

Less than one percent of the children experienced complications such as endocarditis (heart infections), cardiac valve leaks and arrhythmias (heartbeat disorders).

Fewer controls

Chief Physician and Paediatric Cardiologist, Siri Ann Nyrnes at the Children’s Clinic of St. Olavs Hospital and NTNU praises the study by Jarle Jortveit and his associates. She says this contributes well in calming the fears of parents whose children were born with such heart defects.

“But in my experience there has already been a shift in recent years toward fewer check-ups and follow-ups of children with ventricular septal defects (VSD).”

Nation-wide meetings among paediatric cardiologists have recommended fewer controls and an earlier ending of such examinations for children with small and inconsequential holes in the muscular part of the septum, explains Nyrnes.

“We no longer recommend antibiotics as a preventive measure for children with VSD,” she adds.

Previous studies have shown that even the smallest and most inconsequential holes in a child’s septum trigger anxieties and concerns among parents.

“Solid information to the children and the parents is a key thing here,” concludes Nyrnes.

---------------------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling