Wasting water in Norway has consequences for the environment

Norwegians use almost twice as much water as the Danes. These wasteful habits come at a cost.

Even the name city officials in Cape Town, South Africa used to describe their water crisis had an ominous sound: Day Zero. That’s when officials said they would have to shut down municipal water supplies and residents would have to queue for water.

Fortunately for Cape Town, the crisis was avoided due to significant water restrictions and strong winter rains in 2018. But the near-crisis in Cape Town is more relevant than you might think in countries like wet, rainy Norway. Norwegians use twice as much water every day as their neighbours in Denmark.

This, public officials say, results in costly waste that’s bad for the environment. Saving water, even in a country like Norway where there will likely never be a Day Zero, is something that residents should learn to do, they say.

Expensive water down the drain

Norwegians consume an average of 180 litres of water per person every day, according to data from Statistics Norway for 2018. This is almost twice as much as the Danes, who will soon consume just 100 litres a day, according to Danva, an industry organization for Danish water companies.

But is there really any reason to save water in Norway? Could residents save money? Electricity? Or the environment?

Water officials from the municipality of Oslo say the answer is a clear “yes”.

Frode Hult is section manager for the Aquatic Environment at Oslo’s Water and Wastewater Administration. He says one important reason the answer to these questions is an unqualified yes is because there’s a lot that goes into producing water that runs out of the tap — and even more that needs to happen after the water we use has run down the drain.

Environmental impact underestimated

Christian Vogelsang, a researcher at the Norwegian Institute for Water Research (NIVA), believes many people are unaware how water use affects the environment.

“People don’t really think about the environmental impact of producing tap water, it’s true. The size of the impact also depends quite a bit on how you calculate it and where you live,” he says.

In Norway, tap water is first purified, then pumped to households — and then treated again before being discharged into lakes, rivers or the ocean.

Tap water in Norway is considered to be of excellent quality, and Norwegians drink tap water from mostly any tap.

This effort requires a lot of electricity, transport and not least, chemicals.

Hidden power costs

Consider this: using cold water in your home doesn’t generally affect your electric bill.

Nevertheless, the municipality where you live uses a lot of electricity to provide this water to you.

It is not easy to find recent numbers that document this, at least in Norway, because, municipalities have not been required to report how much electricity they use in the water and wastewater sector.

But in 2014, Norwegian municipalities spent more than NOK 400 million — or roughly EUR 40 million — on electricity for water and sewage. This represented more than one-tenth of the total electricity consumption of the municipalities, according to a document prepared on behalf of the trade organization Norsk Vann (Norwegian Water).

Wastewater treatment particularly energy intensive

Once wastewater reaches a treatment plant, it takes a lot of energy to clean it to a level where it can be discharged, Vogelsang says.

Wastewater often contains a mix of food debris, shampoo, detergents — and urine and faeces, of course. Consequently the water has to go through an extensive purification process to remove those substances.

Wastewater can be purified in three different ways, using mechanical, chemical and biological treatment. Ideally, wastewater should be treated using all three approaches.

Chemical treatment relies on chemicals that remove substances from water, while biological treatment uses living bacteria found naturally in sewage to break down a number of other substances.

The bacteria break down waste materials by digesting them, which occurs without oxygen, and by decomposition, which requires the presence of oxygen.

Vogelsang says it requires a lot of electricity to provide bacteria the air they need to do their job.

Transport and greenhouse gas emissions

When bacteria break down waste materials, they also produce greenhouse gases such as CO2, methane and nitrous oxide. Methane gas can be used to power the treatment plant. In some plants, methane can also be used as a biofuel for buses, for example.

But so far, no plants capture CO2 or nitrous oxide, Vogelsang says. This means that these greenhouse gases are released into the air.

Another important source of greenhouse gas emissions is vehicle transport to and from treatment plants. Vehicles are used to carry the chemicals used to purify both drinking water and wastewater.

The chemicals themselves are also not good for the environment – however, researcher Vogelsang from NIVA isn’t sure whether using less water will decrease the use of chemicals.

Can Norway run out of water?

What about the actual provision of water? Can we run out of water in Norway?

“Few people experience that tap water for drinking is scarce in Norway. Last year was an exception, when we had to introduce water savings – people were not allowed to water their gardens and were asked to limit their use of clean tap water. For now that was an exception to the norm, but prognoses show that climate change might make this happen more often”, says Vogelsang.

In Oslo, the situation is already precarious. 90 per cent of the tap water in the city comes from a single source, Maridalsvannet, cleaned at Oset cleaning facilities.

“This makes us vulnerable to situations that might affect either this water or the cleaning facilities. Two consecutive dry years for instance, could put a strain on water provisions in Oslo, says section manager Frode Hult from Oslo’s Water and Wastewater Administration.

Oslo is therefore working to establish a new source for tap water by 2028.

Population growth in Oslo also puts a strain on the water supplies.

So there would be a lot to gain from people using less water, according to Hult.

Out of sight, out of mind?

“We have been working on campaigns to increase peoples’ understanding of the value of our excellent tap water, which serves as our drinking water. And the importance of not overusing this resource.”

Norway's high consumption indicates that the message hasn’t quite hit home. Norwegians are more concerned with whether our tap water is safe to drink, than if we waste it.

“The understanding in the business is that the work that goes into this is somehow hidden”, says researcher Vogelsang.

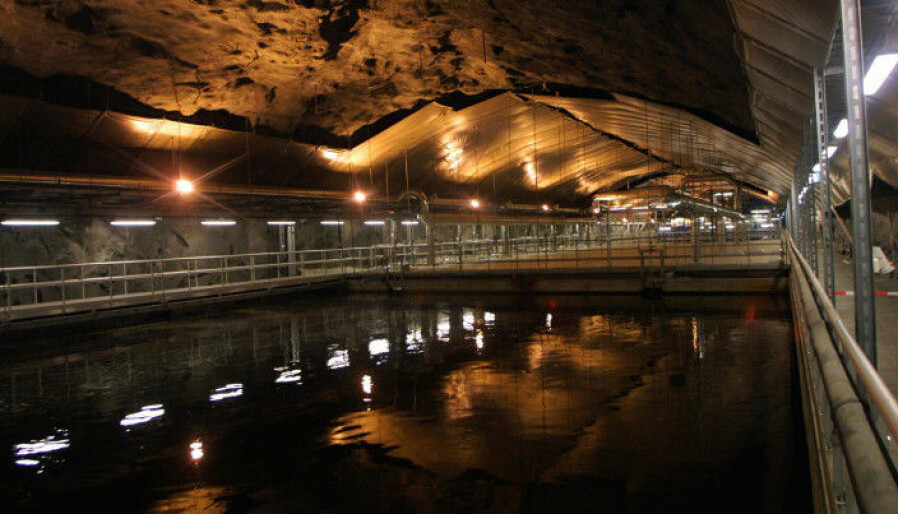

“Most of the infrastructure is underground, both the cleaning facilities and the pipes. The cleaning of this water “just happens”.”

———