How climate change is already affecting the Barents Sea

There is significant variation, but the trend is moving towards a more Atlantic climate.

Researchers are now concluding a massive project that has been ongoing since 2018.

In The Nansen Legacy, 300 researchers from several Norwegian institutions have studied how a changing climate and human traces affect the ecosystem - particularly in the northernmost parts.

Researchers have conducted annual expeditions by ship, conducted experiments, and placed sensors in the sea.

They have also used core samples to examine history going back 10,000 years and run climate models to project the future.

Marit Reigstad, who led the project, explains the changes they are observing in the Barents Sea so far.

Divided in two

The Barents Sea can be said to be divided in two, explains Reigstad, a professor at UiT The Arctic University of Norway.

In the northern part, there is ice during winter.

The sea ice there is crucial for animals such as ringed seals, polar bears, polar cod, and other species tied to the ice.

The ice edge zone is a buffet for many species in spring when plankton and ice algae bloom.

In the southern part of the Barents Sea, there is open sea, abundant fisheries, and oil and gas fields.

The management of the Barents Sea moving forward must be based on knowledge, says Reigstad regarding the project's background.

The climate zone is shifting

In the northern Barents Sea, where seawater freezes in winter, there is a polar climate.

In the south, the climate is more Atlantic, similar to that of Tromsø or Bergen, says Tor Eldevik, head of the Geophysical Institute at the University of Bergen, who also co-led the project.

Most viewed

To understand what is happening in this marine region, one can look at Svalbard, located in the northwestern corner of the Barents Sea.

"Svalbard is melting as we watch," says Eldevik. "This is because Svalbard is fixed geographically, while the climate zone is shifting northeastward toward the Arctic Ocean."

Some of the changes happening beneath the surface in the Barents Sea will be just as dramatic, he adds.

Animals dependent on the polar climate are being pressured, while those favouring a more Atlantic climate are gaining ground.

Ocean currents play a key role

The climate in the Barents Sea is influenced by both the atmosphere and the Atlantic current - a continuation of the Gulf Stream that brings warm water northward.

Both factors impact the temperature and the sea ice, explains Marit Reigstad.

There is significant variation between years, she points out.

When the ocean current is strong and carries more or warmer water, the region becomes warmer and there is less ice.

"It becomes a system more influenced by the Atlantic than the Arctic. This is also reflected in the species we find," she says.

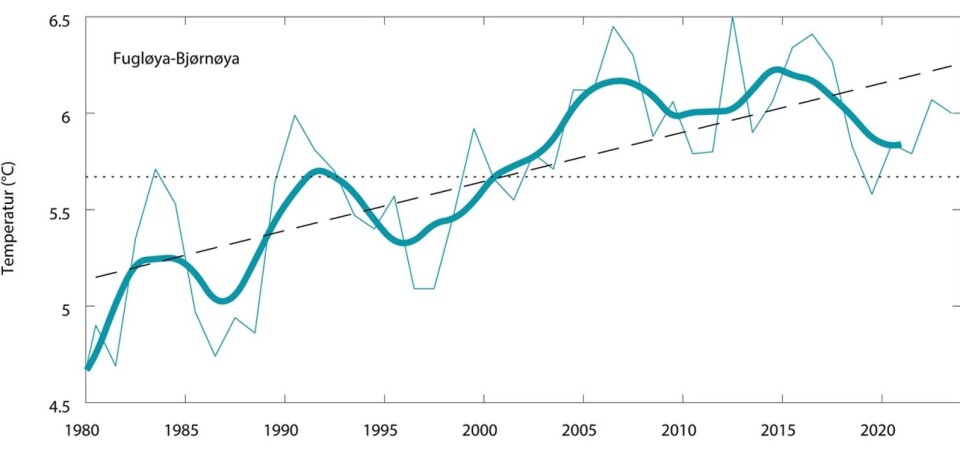

Sea temperatures in the Barents Sea have increased by an average of 1.5 degrees over the past 50 years, according to the government's report on ocean management.

Natural fluctuations

In recent years, it has become slightly colder again with a bit more ice.

This is due to a natural climate fluctuation that temporarily counteracts warming.

"We have regular, direct measurements of the Atlantic current dating back to the 1950s. What characterises these measurements is a generally warming trend," says Tor Eldevik.

Ice is moving more

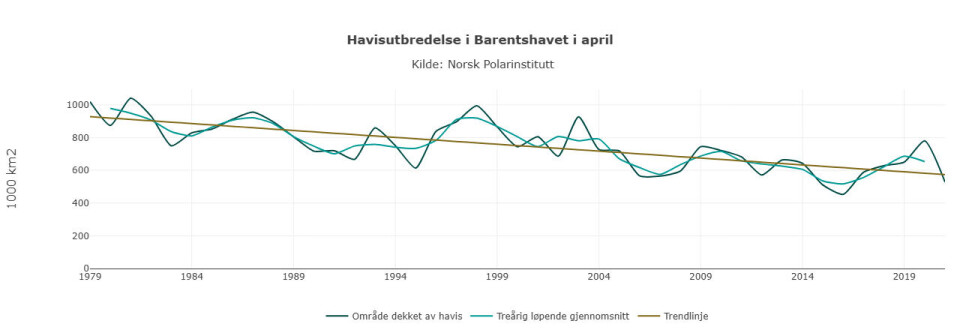

Sea ice has seen a long-term reduction in coverage.

It has become thinner and is more affected by waves and wind. The ice breaks up more easily and drifts around.

Ice floes also drift in from the Arctic Ocean and the Kara Sea. This ice is often thicker and arrives later in the year.

In recent years, winter ice coverage has been relatively normal.

Earlier spring

Researchers have observed that spring is arriving earlier in the northern Barents Sea.

Spring advanced by an average of two days per year from 2000 to 2016, explains Reigstad.

This shift resulted in spring arriving a full month earlier over that period.

While this means a longer growing season and more algae growth, it does not necessarily lead to more of the algae species that provide food for fish, Reigstad explains.

2016 marked a warm peak year in the Barents Sea. Since then, temperatures have cooled slightly again.

"In general, at higher latitudes, winter is being squeezed from both ends. Spring arrives earlier, and autumn lasts longer," says Eldevik.

Quick response

Wildlife is responding to the changes taking place.

Fish and algae floating in the water are moving and can quickly react to higher temperatures or increased food availability.

Atlantic fish species spread out when there is little ice and a warm summer season, but they disappear again if the next year is colder.

"Climate and ecosystems are designed to handle significant variability, as that has always been the case in the Arctic," says Reigstad.

"But with the ongoing changes, we see a stepwise shift that favours species that previously lived further south in the Barents Sea," she adds.

Displacing Arctic species

When Atlantic fish species move into areas previously inhabited by Arctic species, the Arctic species may be eaten or face competition for food.

If temperatures become unfavourable and ice diminishes, Arctic species are likely to be pushed further northeast.

However, they cannot continue indefinitely to the north. The Barents Sea is relatively shallow, averaging 230 metres deep. Beyond it, the Arctic Ocean is a deep-sea environment.

Changes are also occurring on the seabed, though more slowly. Species are gradually shifting northward, and this is being observed across the entire region, Reigstad notes.

She references a study from the project that analysed data going back to 1900. The changes occurred in multiple phases, most notably after 1980, with larger, synchronised shifts observed across broader areas after 2000.

Unexpected southern visitors

Researchers also used trawls in the Arctic Ocean to see what they could catch.

"We were quite surprised," says Reigstad.

They caught only seven fish but found more jellyfish and zooplankton. What stood out was that many of the species came from southern regions.

"This shows how ocean currents act as vital transport belts," says Reigstad.

Fish, larvae, and zooplankton are hitching a ride northward. If the waters warm, they could establish themselves permanently.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.