Methane leaks from cracks in the Barents Sea seabed

But does it affect the climate?

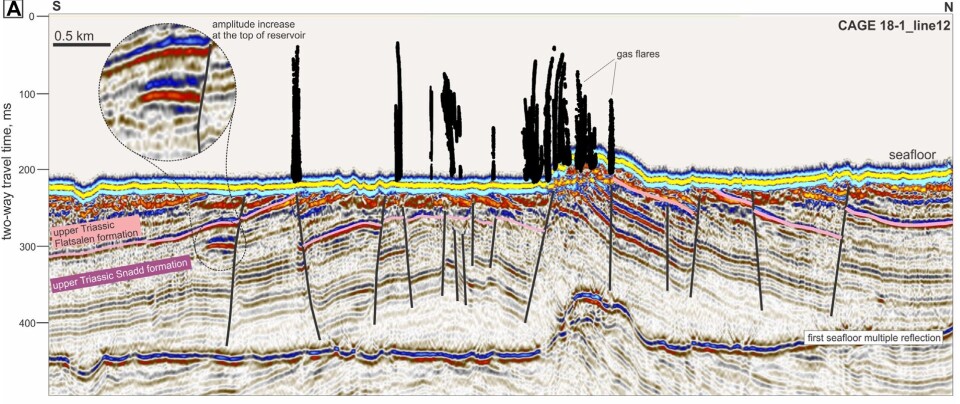

The seabed in parts of the Barents Sea is riddled with cracks. Methane gas seeps out of some of these cracks, forming columns of gas rising from the seabed.

While methane gas is a key component of the natural gas extracted from oil platforms, these emissions are natural, not industrial.

The gas leaks from large reservoirs of oil and gas beneath the seabed, emerging from thousands of cracks and faults.

Seabed surveys have identified over 21,000 locations where methane rises from the seabed. This finding is detailed in a new study published in Frontiers in Earth Science.

Natural leakage

“This area is unique because there’s so much natural leakage,” Monica Winsborrow tells sciencenorway.no.

She is an associate professor at UiT The Arctic University of Norway and one of the researchers behind the new study.

The researchers estimate that around 9,800 tonnes of methane leak through these cracks into the seabed and ocean every year.

“We believe there’s one or two orders of magnitude more leakage here compared to other similar marine areas,” she says.

One key factor in the high leakage is that several ice ages have eroded the seabed over time.

“Over the course of two million years, multiple ice sheets have grown and disappeared. The ice sheet erodes the seabed, so the hydrocarbons come closer and closer to the seabed,” she says.

The study is based on a large-scale mapping of the seabed around Norway, called Mareano, conducted by the Geological Survey of Norway (NGU). This research forms an important part of the knowledge base for seabed mining, which you can read more about here.

But where does all the methane go? And does it reach the atmosphere?

Very little

Researchers are not certain how much of this methane reaches the atmosphere, but it's likely a very small amount.

They estimate that just 0.05 per cent of the total methane emissions reach the atmosphere, though there is significant uncertainty.

Most of the methane is consumed by microbes living on the seabed, with some being carried away by ocean currents, explains Winsborrow.

The methane is oxidized, breaking down into oxygen and CO2.

Winsborrow notes that there are still many unknowns, such as how these emissions vary throughout the year, and whether microbial activity changes with the seasons.

More precise air measurements over these marine areas are needed throughout different times of the year to better understand the processes.

Methane as a greenhouse gas

Despite this leakage, the Barents Sea is a relatively minor source of atmospheric methane compared to other sources.

In total, researchers estimate that around 600 million tonnes of methane enter the atmosphere every year, although there are large uncertainties around this number.

While carbon dioxide is the most commonly discussed greenhouse gas, methane also plays a significant role in global emissions.

Methane is far more effective than CO2 at trapping heat, making it a much more potent greenhouse gas. In fact, it is 28 times more effective, according to the United States Environmental Protection Agency.

Roughly one-third of all methane emissions come from natural sources.

“Most natural methane emissions come from wetlands,” says Ragnhild Bieltvedt Skeie. She is an atmospheric researcher at Cicero – Centre for International Climate Research.

Some methane also come from geological processes.

However, the majority of methane emissions stem from human activities.

“Over the past ten years, human-related methane emissions have increased, and we’ve seen a significant rise in methane concentrations in the atmosphere,” she says.

Skeie explains most of these emissions comes from livestock farming, waste management, and oil and gas production.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Reference:

Serov et al. Geological and glaciological controls of 21,700 active methane seeps in the northern Norwegian Barents sea. Frontiers in Earth Science, vol. 12, 2024. DOI: 10.3389/feart.2024.1404027

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.