Drugs that didn’t keep their promise

The medicines were called “disease-modifying” because they were supposed to slow down the disease itself. But earlier medications for arthritis didn’t do this. Several of them, however, had dangerous side effects. Why did patients take them anyway?

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) attacks the support structures of the body and causes severe pain. It eats away at the joints and bones until you can barely move.

Patients and doctors are both in dire need of medications that not only relieve the symptoms but can slow down the damage to the body.

And in the 1980s several medications came on the market that claimed to do just that. They inaugurated a new medical frontier and were called disease-modifying drugs.

Several drugs were put into this category. Gold was one of them. It had been in use for a long time, against a number of disorders.

The disease-modifying name was also given to penicillamine, chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, cyclophosphamide and azathioprine. They were sold under names like Cuprimine, Sendoxan and Imurel.

Yet evidence showing that gold or the other medicines categorized as disease modifiers worked in this way was scarce. Cochrane research reviews for these agents later showed that they only relieved the symptoms.

How could these medications still be classified as drugs that promised to change the course of the disease?

Promised improvement

Jonas Kure Buer set out to answer this question. Buer is a social anthropologist at the University of Oslo and has studied the DMARD category of drugs.

The promise lies in the name itself: disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD).

"It's a drug that comes with a promise that if you take it, you’ll be better off in the long term than if you don’t take it," Buer says.

And once the term became established, the name made it possible to offer a medicine without documenting its efficacy.

Kept patients from losing hope

Buer recently wrote his doctoral dissertation on how patients and healthcare professionals relate to the treatment of rheumatism.

As Buer talked to doctors in a hospital and repeatedly heard DMARDs being referenced, he began to wonder how the “disease-modifying” term had actually come about.

He dug into the PubMed archive, looking for scientific articles, and found that the use of the word was well established among professionals as far back as 1980 – long before any drug actually worked to slow down the disease itself.

"What I thought were indications for a drug, instead described what patients hoped the drug would do," says Buer.

He doesn’t know why DMARDs evolved this way, but he thinks that the name was effective.

“The category probably came about because someone hoped, or maybe needed to believe, that a medication was disease-modifying. Whether that was a drug manufacturer selling it to a doctor or doctor giving it to a patient,” says Buer.

He believes that in a situation where the doctors had little to offer the patients, the term created the feeling that something stronger was available.

The term “may help patients to keep thinking that their situation isn’t hopeless,” says Buer. “Many patients are in desperate straits.”

If the treatment wasn’t able to stop the bone erosion, the DMARD term could at least prevent the erosion of hope, he says, and points out that this also helped boost sales for the pharmaceutical industry.

Dangerous drugs

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic disease, but can be easier to live with if the disease process is attenuated. This is precisely what a disease-modifying drug should do.

The medications that first carried this name were potent drugs with numerous, and sometimes nasty, side effects such as cytoxicity or attacks on the immune system.

Kidney damage, liver poisoning and bleeding are just some of the injuries that can occur.

Four out of the five DMARDs that Cochrane examined had serious adverse reactions, according to the research reviews.

Only hydroxychloroquine was cleared. It is currently sold under the name Plaquenil.

Took the risk

Many patients with RA were nevertheless willing to take the chance. The alternative was permanent inflammation that eventually destroyed the joints.

Buer imagines that it was a clear benefit 30 to 40 years ago for doctors to offer patients a pill designated as “disease modifying.”

“Should they have instead told patients that they had a drug with severe side effects and with no proven efficacy?” he asks.

But how in the world could doctors give these medications to patients without anyone reacting?

The doctors also believed in them and in their experience the drugs seemed to work, explains an Australian expert on anti-rheumatic drugs.

In an e-mail to forskning.no, Professor David A. Joyce, who heads the lab in the Department of Pharmacology at the University of Western Australia, noted that at a time when these debilitating illnesses didn’t have any cure, the treatments at least seemed to help some patients.

No better than a placebo

"We have a better understanding and more complete picture today," Joyce says.

Later research on disease-modifying effects has shown that neither gold nor penicillamine has any benefits.

Patients show similar improvement when given a placebo in population studies, he says.

Joyce believes that people changed their view of the old medicines changed as new drugs, like methotrexate, appeared to work better.

Some people were already asking questions back then. Thanks to them, better medications were developed, he says.

Close contact with the doctor

Early DMARDs required patients to visit their doctor often, due to the drugs’ serious side effects.

Buer believes the close contact between doctor and patient helped patients not to lose hope.

Joyce has read the Buer’s study and supports this interpretation. He believes hope may explain why patients found that the drugs worked.

"The positive effects were probably a product of the help, support and optimism that were created in the relationship between patient and doctor. More recent studies have shown the same effect with placebo, Joyce writes in his e-mail.

Medications that work

Today, new types of DMARDs can actually slow down arthritis. However, these substances also have side effects that have to be assessed against their benefit to patients.

Methotrexate is among the most commonly used disease-modifying drug.

And one of the first five DMARDs, hydroxychloroquine, was later found to be effective in combination with methotrexate and sulfasalazine, according to an article in the Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association by Norwegian researchers.

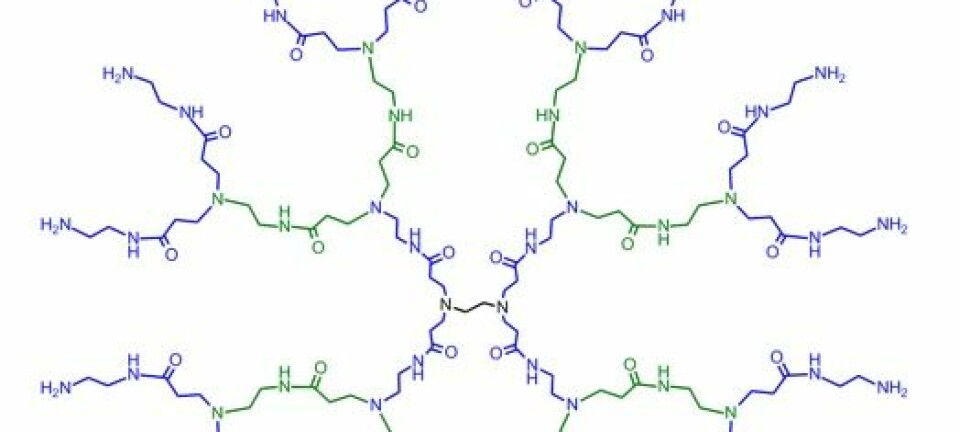

In addition to the synthetic medicines, biological drugs, such as TNF inhibitors, have been found that bind to the cells and block the substances that destroy the joints.

"New DMARDs used for arthritis aren’t approved today without evidence that they prevent the development of bone erosion," says Anna-Birgitte Aga, a specialist in rheumatology research and a general practitioner at Diakonhjemmet Hospital in Oslo.

Both European and American health authorities require X-ray data that shows that new disease-modifying arthritis drugs actually prevent joint damage.

Through several research projects, Aga and colleagues have found that new types of DMARD work in this way.

“Half of the patients now become symptom-free. Fifteen years ago, only four per cent achieved similar results,” she says, referring to the ARCTIC study and the NOR-DMARD study.

"We also found that it’s better to start treatment early, follow the patient closely and adjust the treatment along the way,” she adds.

Aga finds Buer’s article interesting historically, and thinks he has a point in the fact that when the medicines were used, doctors didn’t have enough evidence for their disease-modifying effect.

Were patients tricked?

Buer believes that the promotion of the earlier drugs was generally well intentioned.

"I don’t like to talk about people being tricked," he says.

But the social scientist thinks the result was nevertheless that the term DMARD was a linguistic construction rather than a real description of the drugs.

When studying the use of the word, his was able to put his experience studying other cultures to good use. He used the same anthropological methods to understand the pharmaceutical world, because it too has its own culture and creates its own language.

"It's important to know that the words used to categorize drugs are not necessarily categories that reflect reality,” Buer says.

-----------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Scientific links

- Jonas Kure Buer: To stop the erosion of hope: the DMARD category and the place of semantics in modern rheumatology. Inflammopharmacology, Vol. 25, No. 2, 2017. DOI: 10.1007 / s10787-017-0320-9.

- Jonas Kure Buer: A history of the term “DMARD”. Inflammopharmacology, Vol. 23, No. 4, 2015. DOI: 10.1007 / s10787-015-0232-5.