Politics blend with art in modern protest on old chinese platter

New and old, politics and art meet when potter Paul Scott states his protest against the arrest of Chinese artist and dissident Ai Weiwei.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

When the contemporary Chinese artist and regime critic Ai Weiwei was arrested in April 2011, artists found their own novel ways of protesting.

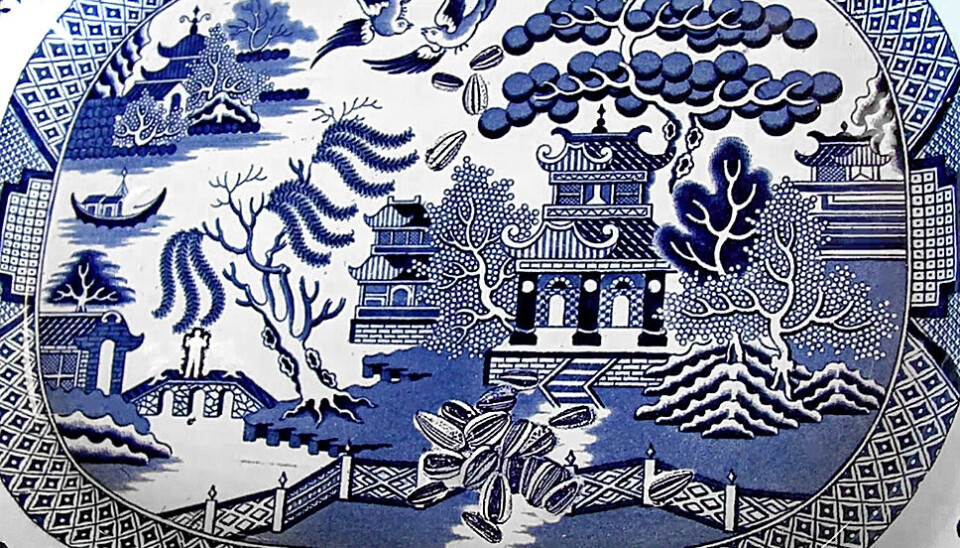

British ceramics artist Paul Scott contributed his bit in the piece titled A Willow for Ai Weiwei.

Senior Curator Knut Astrup Bull at the Museum of Decorative Art and Design in Oslo has picked out this platter as his favourite item in the museum’s collection, and shares the story of the platter.

Missing artist in old chinese motif

Ai Weiwei’s whereabouts were uncertain for a while after he was arrested by Chinese authorities.

The British artist Paul Scott made a statement by placing his missing colleague on a porcelain platter − a material with deep Chinese roots.

Scott has added several details pointing toward the Chinese artist in the platter, which is based on antique Willow-patterned porcelain.

The motif in the traditional blue-and-white Willow pattern refers to a Chinese love story. But this fable wasn’t fully Chinese, if Chinese at all.

The pattern was the brainchild of the Briton Thomas Minton from around the late 1700s and versions of the story were made up, based on its elements.

“Why Scott selected this particular platter as his point of departure for commenting on the jailing of Ai Weiwei is uncertain," says Bull. "But I think it’s because the motif provided an opportunity for adding the elements he wanted. Also, the story in the motif is about somebody who is being persecuted."

The motif includes two lovers who cannot have each other because the young man is beneath the woman’s rank.

They are seen fleeing across a bridge, but in lieu of the lovers, Paul Scott has placed an empty outline of Ai Weiwei.

From exclusiveness to mass produced porcelain

The vase Ai Weiwei drops in the picture Dropping the Urn, is allegedly from the Han Period. Han is the dynasty that ruled when porcelain production first took off in China, in a 400-year period from about 200 years before to 200 years into what now is designated the Common Era (CE), starting with 0 AD.

Both the Chinese Ai Weiwei and the Briton Paul Scott have also used traditional porcelain objects in their art. China and England are both key to the history of porcelain.

It was China and artisans of the Chinese emperor who first started the world’s porcelain production, and the manufacturing methods were originally a trade secret.

“When the Europeans came to Asia and started trading with China, the country started producing china for export. It wasn’t their best porcelain, but it was still very expensive,” says Bull.

According to him, in the 18th century a little set of cups could cost as much as a small house in Oslo. That’s why it was called white gold.

The move and collapse

Europeans eventually learned to manufacture their own porcelain and it became cheaper. The revolution that brought it to the mass market occurred in England in the mid-1700s.

The Britons discovered a method of transferring motifs onto the porcelain in cobalt blue.

This is the period in which Thomas Minton created the Willow pattern, which was given an oriental and dramatic love story. The pattern became immensely popular and production has continued right up into modern times, explains the curator.

“In the design industry there’s a large cult based on the blue-and-white pattern, and particularly the Willow pattern.”

Layer upon layer

Bull is especially fond of A Willow for Ai Weiwei because it contains so many allusions and layers of meaning.

It’s not just a commentary on the Chinese government’s jailing of a dissident artist, but the piece also relates to ideas about the original traditions of porcelain and the present-day decline of the porcelain industry, explains Bull.

In England the industry is now flagging out to countries with lower production costs. Also, current trends in dinnerware shy completely away from decorative patterns.

Although young people may not be buying much blue-and-white porcelain these days, they could have childhood memories of desserts at grandmother’s home which may have been served on Willow pattern plates.

Bull thinks the pattern is still very widely known.

He has worked with the development of theory in contemporary crafts.

He says crafts have been significantly defined from a pictorial arts context and from there they have been considered creative utility articles. But a change has occurred, as exemplified in A Willow for Ai Weiwei.

“Whereas the pictorial arts were deemed as comments on reality, handicrafts were viewed as part of this reality. So crafts have not had any content.”

But a lot of changes occurred in the 1990s, and one of them is actually the platter we have here.

Who’s the artist?

When the crafter starts to use ready-made objects, the question arises: where is the craft here?

“Then it’s uncertain whether the handicraft as a work of art really lies in the making of the object at hand,” says Bull.

When asked where the work of art is in the platter, if it’s in Paul Scott’s work, a mid-19th century industrial copy, or in the work of the potter who first made it in 1780, Bull answers that it is definitely in Paul Scott’s work. But the new piece of art is also a meeting point and a discussion between contemporary crafts and the old traditions.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Read this article in Norwegian at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling