The deep blue Arctic Ocean: A scientific diver's tales of life under water

"I love the ocean, I love the Arctic, I love the knowledge of this stunningly beautiful world I have gathered over the years. This is why I wanted to become a marine biologist."

The buzz and hassle have paused for a moment.

I am under an ice ridge in the Arctic Ocean.

There is 15 meters of sea ice over me and some 3000 meters of water below.

The world around me is deep blue except for some white patches of ice and the blackness of the abyss under me.

Silence. Desolation. Love.

I let my imagination run thinking about all the creatures that might swim somewhere below me in the darkness.

There was a walrus sighting behind our ship just before I went in the water. Could that walrus come and check me out? Or perhaps there are Greenland sharks swimming around somewhere down there? A giant squid or a Russian submarine?

I am alone.

So alone and far away from everything that is practically possible for the meager human being like me.

Far away from land. Closer to the North Pole than to a city. Some 30 meters from our dive hole.

The water is -0.9 degrees Celsius. A degree warmer than yesterday.

There are so many places I could be right now: home, in the warmth of our research vessel, somewhere on a tropical island, perhaps, and there are so many moments that have led me here.

Yet, I would not trade this place and moment away for any of those. All I want is to live this instant to its fullest. I want to be right here, right now. I feel warm, happy, content, and a little bit scared. Alive, in other words.

I look around and see tens of different species. I can name most of them. I can also visualize the interactions around me: who eats whom, how these species got here and what are they doing to survive.

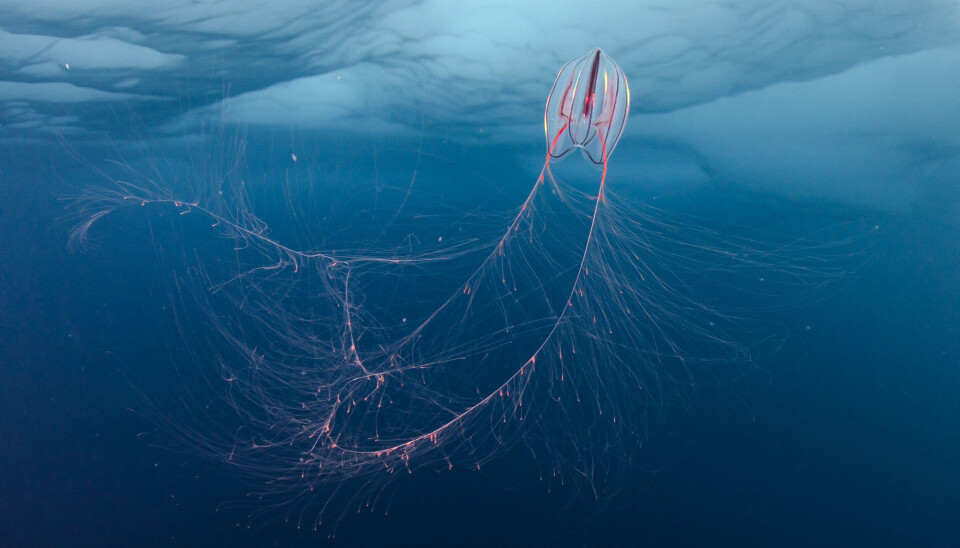

I see Beroe cucumis, a cucumber-shaped jellyfish, drifting by in the current. Mertensia ovum, another jellyfish, which eats copepods, such as Calanus glacialis and is eaten by Beroe cucumis. An amphipod, Apherusa glacialis, crawling on the ice in front of me. It eats dead organic material, ice algae and sometimes copepods, and is eaten by the polar cod and other ice amphipods. Small aggregates of brown algae drifting past reminding that we are here during a very special time of the year – the spring bloom.

The food chains form an interwoven web, which wraps around the physical interactions in the deep blue.

The Atlantic current somewhere down there is bringing warm (2-3 oC) water and Atlantic species, such as the copepod Calanus finmarchicus, into the Arctic Basin. The Polar Surface Layer, a counter-current, makes the sea ice and Arctic species drift southward.

The sea ice collides along the way forming huge ridges of ice which I see on top of me. Animals live in the cavities of the ice. A whole ecosystem that used to be more diverse only a decade or two ago. With melting sea ice, also the ice associated ecosystem is changing.

For moments like this, I love my job extra much.

I love the ocean, I love the Arctic, I love the knowledge of this stunningly beautiful world I have gathered over the years.

This is why I wanted to become a marine biologist.

This is why I sat countless hours in the office staring at my computer screen reading, writing, programming, and doing statistics.

To get here, I had to do a Ph.D., go to a commercial dive school, and devote my life for diving and marine science. To be able to enjoy the dive work, I need to do physical exercise almost every day.

All that for short moments like this, and - for once - I do not regret a single decision I have made.

Right now, I am the most privileged person on the planet.

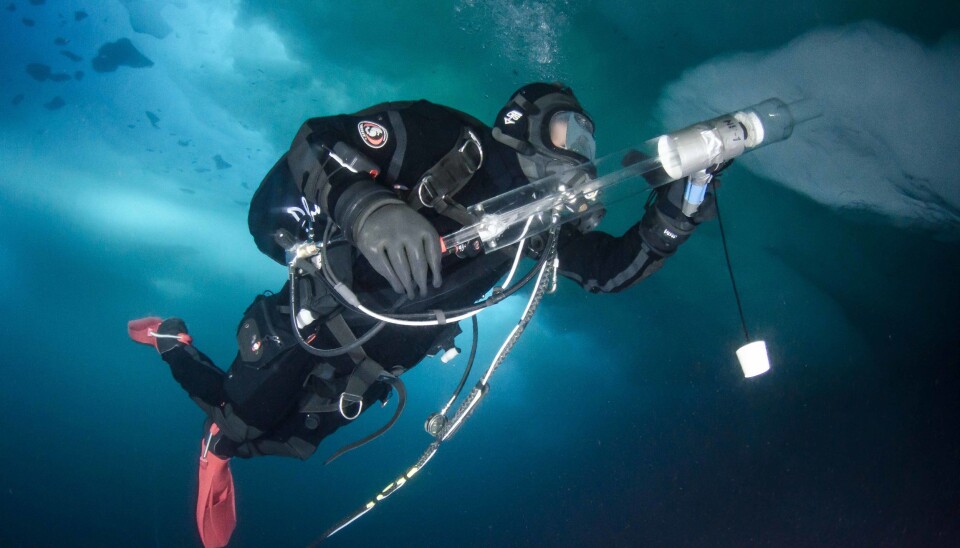

We are on a Nansen Legacy project cruise studying how the ecosystem and environment in the northern Barents Sea and southern Arctic Ocean changes during the year. We have been diving and collecting samples on multiple stations during our journey through the sea ice with the research icebreaker Kronprins Haakon.

Working as a scientific diver onboard contains mostly other activities than diving itself. The workdays have been long. We have spent a lot of time maintaining and carrying gear all over the ship.

When we head out, we need to carry and rig gear in winter conditions. The cold wind and freezing temperatures make everything much more difficult than it would be in the south.

We have made dive holes in 1.5 m thick sea ice.

When we finally get a diver in the water, one needs to act as a tender for other divers, help on the surface placing samples in containers and coordinate deployment of underwater experiments.

Whenever you get to dive, you do not have time to look around because your job is to be as efficient under water as possible.

It is the last day of our diving expedition and my buddies have given me a moment of peace alone under the sea ice in the Arctic Ocean far, far away from everything. The communication system we use is for once quiet, and for that I am eternally grateful.

As is the case with everything, the moment of silence in the deep blue Arctic Ocean is over far too soon. The speakers on my ear crack and tell me to get back to work. There are still many samples to take.

I breathe in and look at the deep blue Arctic Ocean around me for one last time. I hide this memory in my heart and take it with me to the surface. The moment might be past, but I will remember it the rest of my life hoping that there will be many more such moments to come.

This is what I live for.

———

Written by: Mikko Vihtakari

The author is a researcher at the Institute of Marine Research working with deep-sea species and cartilaginous fish (= sharks and rays). Mikko has been working and diving in the Arctic for 15 years. He was hired by the Norwegian Polar Institute to participate the Nansen Legacy expedition.