Frozen in the ice - polar research then and now

Fridtjof Nansen’s bold foray into the Arctic 120 years ago is a classic tale of polar adventure and exploration. But the oceanographic information Nansen brought back continues to influence polar science today.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

One hundred and twenty years ago on 24 June, the Norwegian polar explorer and scientist Fridtjof Nansen set off on an audacious journey. His mission was to investigate the uncharted, unknown area at the top of the world.

But this was no simple journey. Nansen’s approach was to freeze a specially built ship, the Fram, into the polar ice so it could track the polar ocean’s then-mysterious currents.

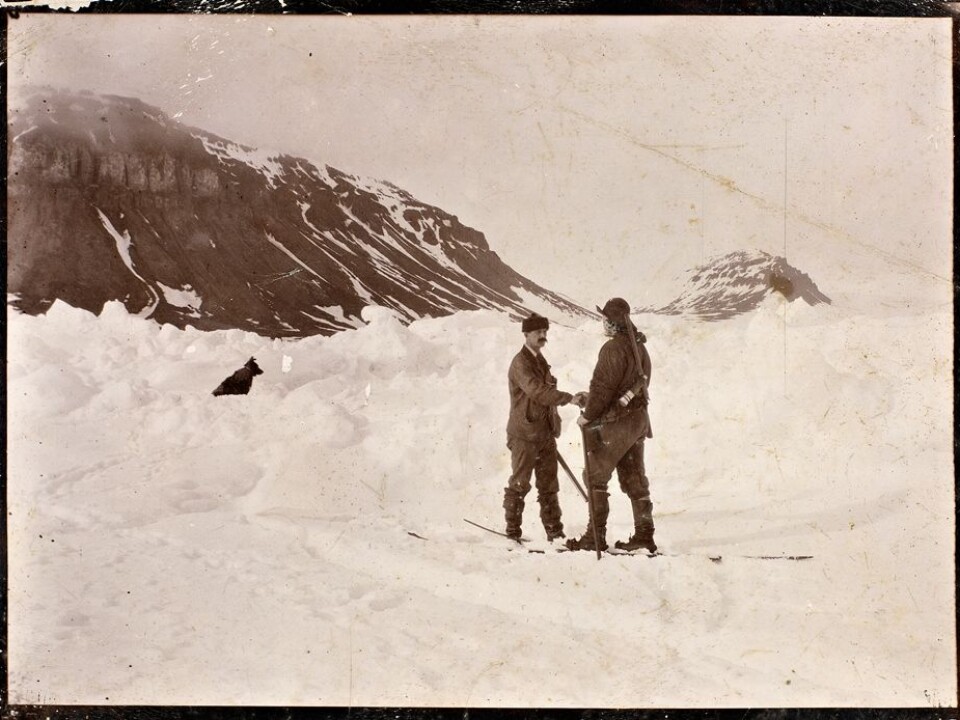

Midway through the Fram’s slow wanderings, Nansen left the ship in an attempt to ski to the North Pole. Both Fram and Nansen returned safely.

The Fram’s three-year scientific expedition is known as a classic of polar adventure and exploration.

But what many polar enthusiasts don’t know is how much Nansen’s exploits went on to shape the world of science as we know it today.

His findings helped lay the foundations for the modern disciplines of oceanography and meteorology. Researchers are still mining the data he collected to better understand the ocean’s secrets.

And one research group has even come up with a proposal for their own 21st century version of freezing a research vessel into the ice to study the Arctic in a changing climate.

A ring of ice

Just before the turn of the 20th century, astronomers could point their telescopes into the sky and study the Moon and Mars, but no one knew what lay in the remotest areas of the Earth, at the North and South Poles.

It was the “era of the telegraph, and telephone, but not yet of radio,” wrote Nansen biographer Roland Huntford. Once an explorer headed into the north, “the first men on the Moon, in constant touch with Earth and a quarter of a million miles away, were less alone.”

Historian Robert Marc Friedman, a professor at the University of Oslo, says that so little was known in the late 1800s about the polar regions that some experts even believed the poles would be warm. One theory was that warm currents, such as the Gulf Stream and Japan Current, met under the central Arctic and provided sufficient heat to keep the sea ice-free.

“It was long thought that the Arctic was surrounded by a thick ring of ice,” Friedman said. “If you were to break through that, there would be an open sea, with warmer temperatures.”

Many scientists also believed there would be land at the North Pole, and that the surrounding seas would be shallow. None of this would prove to be correct, as Nansen’s journey into the ice would show.

Wreckage and Eskimo artefacts

Fridtjof Nansen trained as a neuroscientist, but found his life’s calling in the endless white of the Arctic. After completing his doctoral dissertation in neurology in 1887, he skied with five companions across the unexplored interior of Greenland in 1888.

In 1890, he began to lay plans for his next venture into the unknown. This time, he would use what he postulated was the ocean’s east-west current at the top of the world to carry a boat across the North Pole.

Nansen had reason to believe this current existed, although many doubted it. The Jeannette, an American exploration vessel, had sunk in 1881 off the Siberian coast, but wreckage from the ship was found two years later on the southwest coast of Greenland. The only way the wreckage could have gotten there would have been riding on a current.

Despite this evidence, many polar experts at the time thought Nansen’s plans were nothing short of suicide, and that he and his boat would be crushed in the ice, or stranded on the shore of some as yet undiscovered island.

But Nansen was convinced. Other evidence, in the form of Eskimo artefacts that were clearly from Alaska but that were found on the Greenland coast, added to his certainty.

“The plain thing for us to do”

“Putting all this together, we seem driven to the conclusion that a current flows at some point between the Pole and Franz Josef Land from the Siberian Arctic Sea to the east coast of Greenland,” Nansen wrote in “Farthest North”, his book about the journey of the Fram into the ice.

“This being so,” he continued, “it seems to me that the plain thing for us to do is to make our way into the current on that side of the Pole where it flows northward, and by its help to penetrate into those regions.”

And so, armed with his evidence and his explorer’s status from crossing Greenland, Nansen persuaded the Norwegian government to grant him NOK 20 000, the equivalent of about NOK 7 million today, to build the Fram, a ship specifically designed to withstand the pressures of the ice.

The boat’s now famous design, by a Norwegian naval architect and boat builder named Colin Archer, would enable it to be squeezed up out of the sea ice rather than be trapped in the ice and crushed. That it moved “more like a cradle rocked by an inconsiderate hand than a ship in a seaway,” didn’t matter, according to Nansen biographer Huntford. “A safe ship, as every seaman knows, is an uncomfortable one.”

A long drift and a ski trip

On 24 June 1893, the Fram left Oslo with Nansen and its crew of just 12 men. “The quays are black with crowds of people waving their hats and handkerchiefs,” Nansen wrote.

The boat “heavily laden,” in Nansen’s own words, contained enough food and equipment for the men to survive five years. Nansen, however, believed the journey would take far less time than that.

Three months later, as the Fram sailed into heavy pack ice off of the New Siberian Islands, Nansen ordered the rudder raised and the ship’s drift began.

What followed was an agonizingly slow drift, first east, then finally north. The pace and trajectory were such that Nansen finally decided to set off on skis to reach the North Pole with one companion, Hjamar Johansen, with no intention or hope of finding their way back to the drifting Fram. The pair left on 14 March 1895, and made it as far as 86°13.6′N – the “Farthest North”, the title of Nansen’s book about the Fram and its journey.

Nansen’s adventures – and safe return in 1896 – make for some of the most gripping tales in the history of exploration, complete with eight months spent sharing a reindeer sleeping bag with Johansen in an improvised hut, and an encounter with a walrus that led to their chance meeting with the British explorer Frederick Jackson, who brought them back to civilization.

The Fram, too, made it back safely, just shortly after Nansen and Johansen had returned.

They were able to meet the vessel in Tromsø in northern Norway and sail triumphantly down the coast to jubilant crowds.

This is the first of two articles on Fridtjof Nansen and his polar adventures and research. Also read: Nansen’s legacy lives on 120 years after polar adventure