What IS this mooring business?

Have you ever wondered what happens to old train wheels? Or massive iron chains that nobody wants anymore? Let me tell you – we take them with us and put them on the bottom of the ocean!

It’s difficult to get measurements of the Arctic Ocean and the Barents Sea throughout the entire year.

Simply for practical and financial reason, we cannot be out there with a ship all the time.

So instead, we put out instruments on so-called moorings: At the bottom is a heavy anchor (the fabulous train wheels). Attached to that a release, basically a hook that we can “talk” to when we want to get the mooring back.

And attached to that again is a long, very strong Kevlar rope to which all the instruments are attached.

To make the rope stand upright in the water, floatation like glass or steel buoys are attached at various depths and at the top of the mooring. In the Arctic, where sea ice or even icebergs can drift past over the mooring, the rope ends well below the surface and the top float sits at a depth of 20 m or more.

The instruments on the mooring are programmed to measure in regular intervals for the period they are out in the water – this period can be anything from weeks to a couple of years.

This way, we get data without having to be at sea ourselves – if we get the mooring back!

When we get back to the mooring sites to pick it up, the most exciting moment is when we try to see the mooring on the ship’s echosounder and to talk to the release to see and hear if it’s still there.

Then a command is sent to the release to let go of the anchor, and the floatation carries the rope with all the instrument up to the surface where we can pick them up.

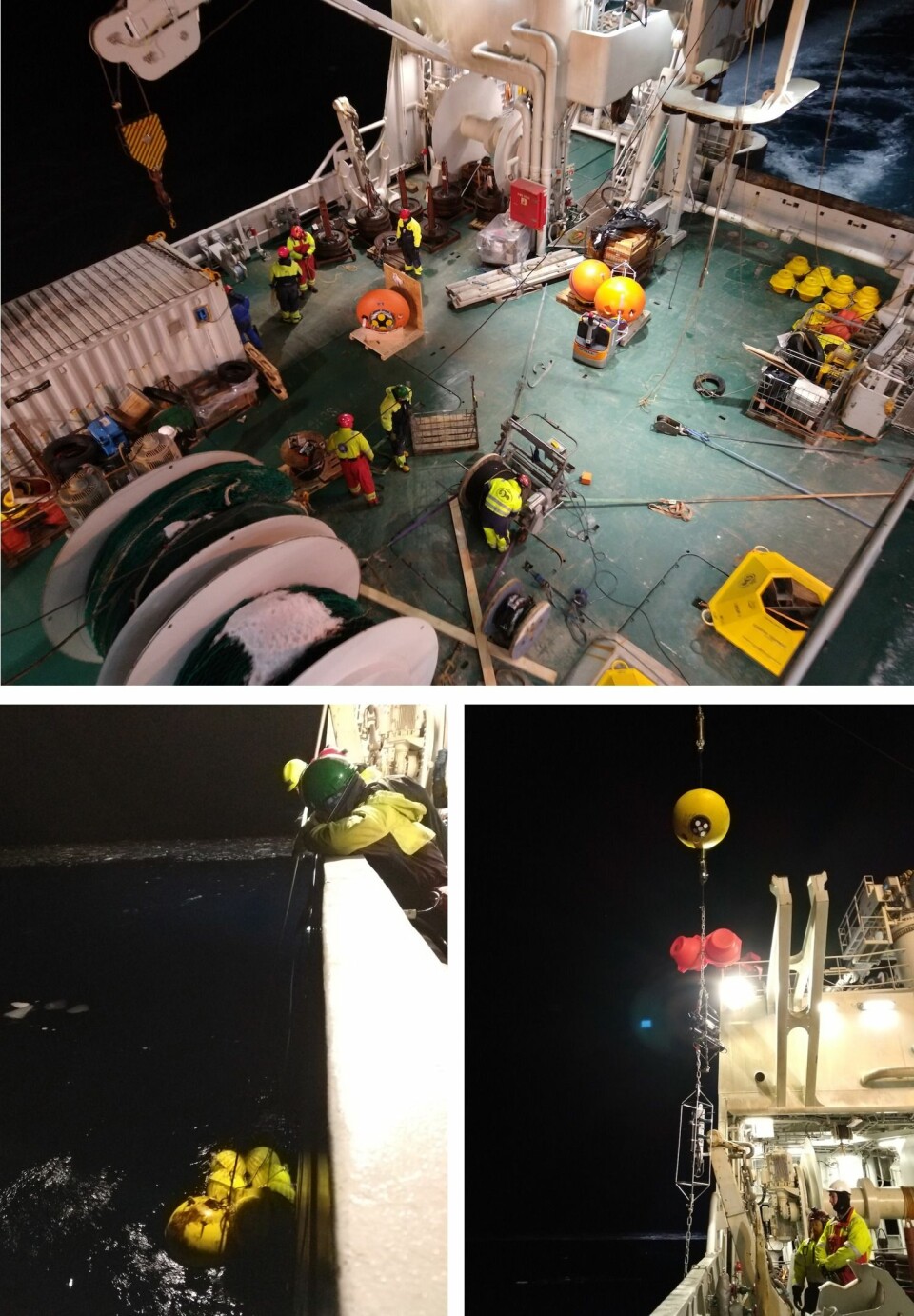

Mooring operations – deployment and recovery – are risky business.

There are heavy weights (a train wheel weighs around 1000 kg), big cranes and winches, and lots of rope involved. Therefore, only people who are directly involved in the process are out on deck, everybody else should stay away.

Of course, basic safety equipment is mandatory, such as helmet and steel-toe cap boots.

The biggest asset for safe deployment and recovery is an experienced crew though – they are the ones trained in operating the cranes and winches. It’s them together with the mooring technicians who do the most challenging work, us scientists maybe get to help by handing over/receiving the smaller instruments or washing them. Otherwise, we stay out of the way until everything is safely stowed away.

Everything becomes even more exciting with sea ice and in the polar night, especially when recovering a mooring.

Sea ice is constantly moving due to wind and currents. To be able to get the mooring to the surface, the boat makes a hole in the ice cover first – but that quickly can get filled in again by ice drifting in!

We therefore check first drift direction, wind conditions, and currents all the way from the surface to the depth the ship-mounted current profilers can cover.

Then we cross our fingers that our estimates of where the mooring should pop up are right and the hole is big enough.

Some of the moorings are equipped with strobe lights making it easier to spot them in the dark. Most aren’t though, and we rely on the ship’s big beams to reach far enough, and on the eyesight of everybody on the bridge. It’s a real team effort which we always have to remember while we wait impatiently to get our hands on the data the instruments have collected!

Meanwhile the train wheels are doomed to stay at the Ocean's floor, slowly corroding away.