The buildings that tell us who we are

Abandoned school houses receive little attention from central cultural heritage authorities. But for local people the modest buildings represent identity and roots.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

It's where your grandmother was taught to read and write. It's the old school house that was abandoned when a new and more modern school opened. It's the old building that is falling apart and few seem to notice.

School houses have been and continue to be important elements of people’s lives.

Research shows the preservation of old school houses has a cohesive effect on local communities. Yet they hardly ever obtain a status that protects them as cultural monuments. Norway’s Directorate of Cultural Heritage has only bestowed that honour to one of several thousand such buildings built after 1860.

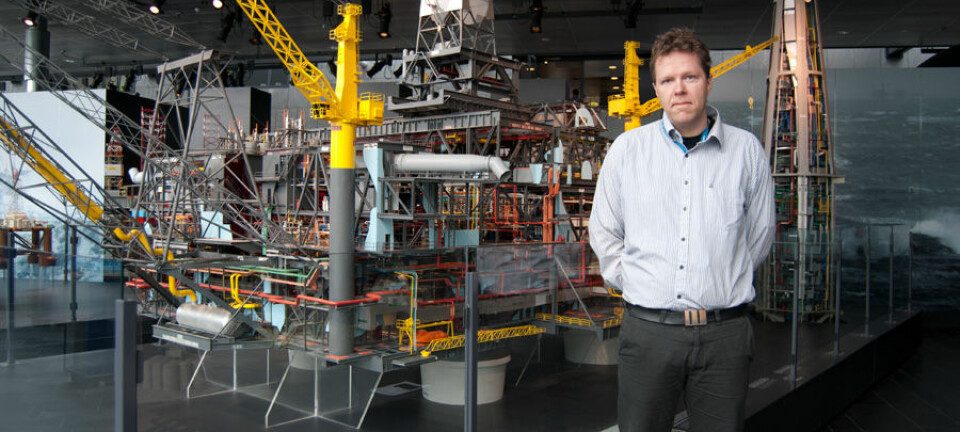

“People are motivated to preserve school houses by their wish to retain their local identity and roots," says Leidulf Mydland, a researcher and the head of the building department of the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU).

For years now he has investigated the way cultural relics are perceived and utilised in a national context, particularly on the local level.

“My research reveals the aspirations of rural communities toward maintaining school houses as assembly buildings − as meeting places for cultural activities,” says Mydland.

More power to the people

His results point toward a definite need to entrench preservation efforts more deeply in local communities. This would require a transfer of responsibilities from central authorities to the grass roots in municipalities.

If implemented, this would give old school houses a considerable rise in status as potential preservation projects.

“People in a local community need to be given a significant boost in influence about what gets protected,” says the researcher.

He has been working on a project that deals with the preservation of the many school houses built after a public education reform was enacted in Norway in 1860.

Although quite a few of these buildings have been restored through private initiatives, many have been torn down or have deteriorated considerably.

Focus on a contemporary perspective

Recent international research on historic relics has focused more strongly on the need to view the role of cultural relics in a contemporary perspective.

“The preservation of cultural relics doesn’t just involve the object itself, but also the process of preserving it and the people involved."

Mydland says the school houses built after the general educational reform link to a milestone in Norwegian history.

“They represented a turning point in our history of education and were also a key factor in the development of democracy.”

Which buildings should be preserved?

Nevertheless, the public school buildings haven’t been regarded as cultural relics, neither by the Ministry of Culture nor by the Directorate of Cultural Heritage, which has only protected one school house from this period.

The NIKU researcher points out that Norway’s current preservation tends to reflect the history of elite governance prior to the establishment of parliamentarism in 1884, rather than the lives and history of the common people.

He adds that only a limited type of building gets protected in Norway when professional antiquarians push all the buttons. Their attention is focused on architecture, aesthetics and monumentality.

Professional expertise is a prerequisite for carrying out good preservation. But Mydland doesn't think the current knowledge from a central position is sufficiently suited to define all that should be preserved.

“Knowledge about the role the building played locally is also needed, and of course the impact it had on people’s lives. This is more important than knowledge about the object per se.”

Our buildings reflect who we are

Mydland sees this as a divergent perception of cultural heritage between the central authorities and the local community.

Although all his research on school houses tends to move the focus from the object to the people, he concedes that architectural and constructional aspects also deserve consideration.

“For instance, we should protect some buildings as symbols which tell us something about Norway as a nation. We should preserve them even if they aren’t appreciated by a local community.”

He thinks Norway needs an explicitly stated policy regarding what they want out of the cultural heritage preservation and a public discourse about what they should preserve.

"After all, our society is reflected by the buildings we protect. They say something about who we are,” says Mydland.

---------------------

Read this article in Norwegian at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling