World Heritage in Danger… What Danger?

The World Heritage Convention is one of the world’s most widely-ratified international treaties. Established with the aim of safeguarding the world’s cultural and natural heritage, most nations are quick to nominate sites though far less likely to manage them appropriately.

Monitoring the threats

Each year, the World Heritage Committee reviews over one hundred state of conservation reports which outline the threats faced by current sites. A fraction of these sites are included on the List of World Heritage in Danger - a separate list maintained under the Convention for those deemed to be facing ‘ascertained’ or ‘potential’ danger.

Composition of the list

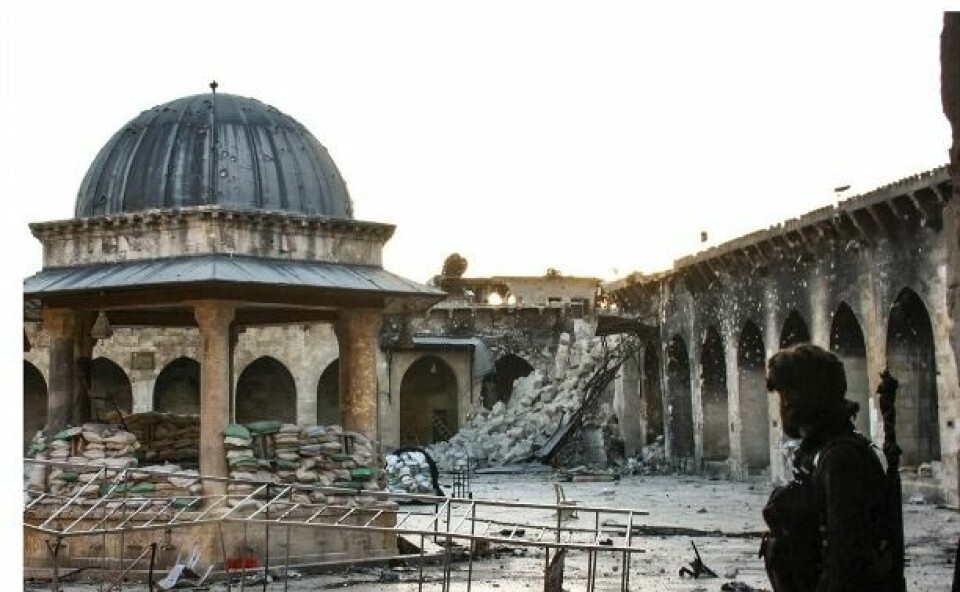

Recent research published in the journal of Transnational Environmental Law has shed light on the use and compilation of the In Danger List. The current compilation is skewed towards sites affected by war and civil unrest with nations such as Congo, Libya and Syria claiming 16 of the 54 listed-sites.

Following armed conflict, development is the second most common reason for listing. Large-scale construction projects (often initiated by local governments) have resulted in threats to iconic cityscapes throughout Europe including Cologne, Liverpool and, most recently, Vienna . In 2009, the German city of Dresden infamously had its World Heritage status revoked following the construction of the controversial Waldschlößchenbrücke bridge.

Costs of Avoiding a Listing

While many states spend big on nominations, others splurge on diplomatic resources to avoid potential In Danger listings. In the late 1990s, Australia fought the Committee tooth and nail to avoid Kakadu being listed In Danger. At the time, Australia argued unsuccessfully that the consent of a state was required before inclusion on the list though Kakadu was still kept off the list by sustained and successful political lobbying. More recently, Australia spent close to half a million dollars to keep the Great Barrier Reef off the In Danger list – money which might have been better spent improving water quality or on coral restoration projects.

Naming and Shaming and Fire Alarms

The In Danger List seems to fulfill two functions. On the one hand, it works like a fire alarm, especially in cases of civil war and unrest. The activation of the alarm alerts the international heritage community to potential threats. Of course, the extent to which the global community can and will act, varies enormously. After the fact, wanton destruction of cultural heritage may indeed be labelled a war crime. On the other hand, when over-development threatens a site, In Danger listings are often initiated by the Convention’s advisory bodies like the IUCN and ICOMOS. In these cases, the list acts like a disciplinary procedure, seeking to ‘name and shame’ recalcitrant states.

New Threats on the Horizon

Now and in the future, the world’s heritage faces new threats. Chief amongst these are climate change and mass-tourism. The responses and responsibilities for these far exceed that of a single state, and probably that of the Convention. The Committee has, for example, refused to list sites In Danger purely on the basis of global warming though it is ‘warming to the task.’ The success or failure of the In Danger List, and indeed the Convention as a whole, will turn on how well it can categorize and respond to these kinds of issues. To do so, it must leave politics at the door, and rely upon the best available scientific advice.