New Viking Age jewellery find delivered to archaeological museum on a platter

The typical Viking Age women’s jewellery had been collecting dust in somebody’s living room for decades. Until last week, when it was all of a sudden delivered by an anonymous source at the Museum of Archaeology in Stavanger.

A set of typical Viking Age women’s jewellery was literally delivered on a platter to the Museum of Archaeology at the University of Stavanger last week.

Archaeologist Kristine Sørgaard was called to the reception and handed a tin platter with a plastic bag on it.

It contained among other things, two oval brooches, an equal-armed brooch, two bracelets and a large necklace composed of a variety of more than 50 beads.

Sørgaard was in no doubt: This was jewellery that once belonged to a Viking Age woman from the upper echelons of society.

“This find has Viking Age written all over it,” Sørgaard says in a press release.

“Both the silver-plated oval brooches, the equal-armed brooch and the two bracelets are typical for this period,” she says.

Some 70 years in somebody’s living room

But where did they come from?

As with the Viking Age gold ring which was recently discovered in a pile of jewellery bought in an online auction, we simply do not know.

The person who brought the jewellery to the museum wishes to be anonymous.

“The person who donated does not know when, how or exactly where the jewellery was found,” the press release states.

According to an article on nrk.no, the person who delivered the jewellery to the museum was not the one who found them. However, they did say that the find was discovered around 70 years ago, in Frafjord in Gjesdal municipality.

“You can see on the surface of the brooch that it is very dusty, so it’s probably been kept in a living room. It’s very important that it has now been delivered to us for preservation,” conservator Louise M. T. Jensen says to nrk.no.

The latest trends

The woman who wore this jewellery was keeping up with the fashion of the time.

Both the oval brooches and the bracelets would have been mass-produced in Scandinavia at the time, says archaeologist Unn Pedersen, who specialises in crafts and the production of jewellery during the Viking Age.

“What they would do is create molds that were unique but based on a model or an existing brooch with the aim of copying it. Something happens during this time where all of a sudden people are concerned with having the same things as others,” Pedersen says.

Archaeologists have found such molds in crafts shops in the Viking Age towns, and can pair them with brooches found in women’s graves.

There is a proliferation of jewellery during the Viking Age, which means that more and more people want to and are able to wear such fashion items.

“This probably has to do with an increase in the levels of wealth among people, which again of course had something to do with all the Viking raids,” Pedersen comments.

A lifetime of collecting the finest beads

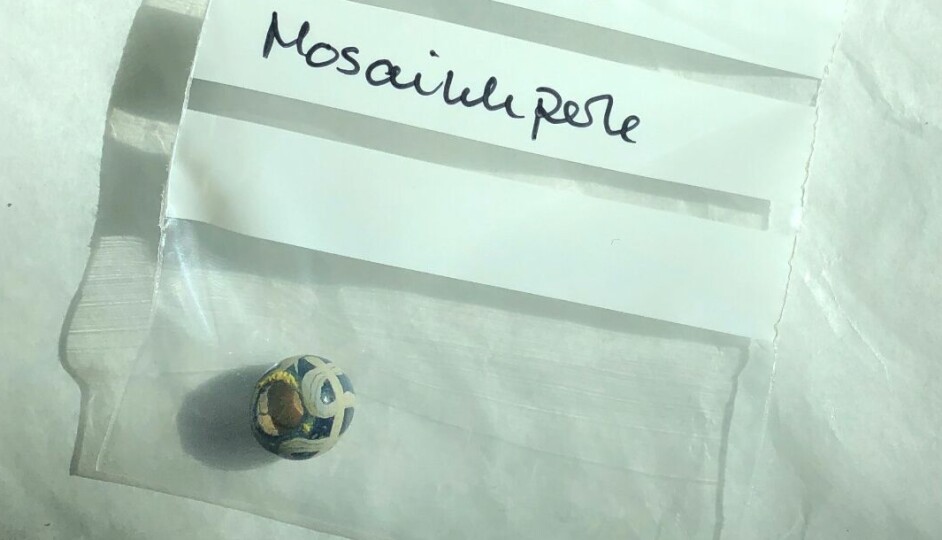

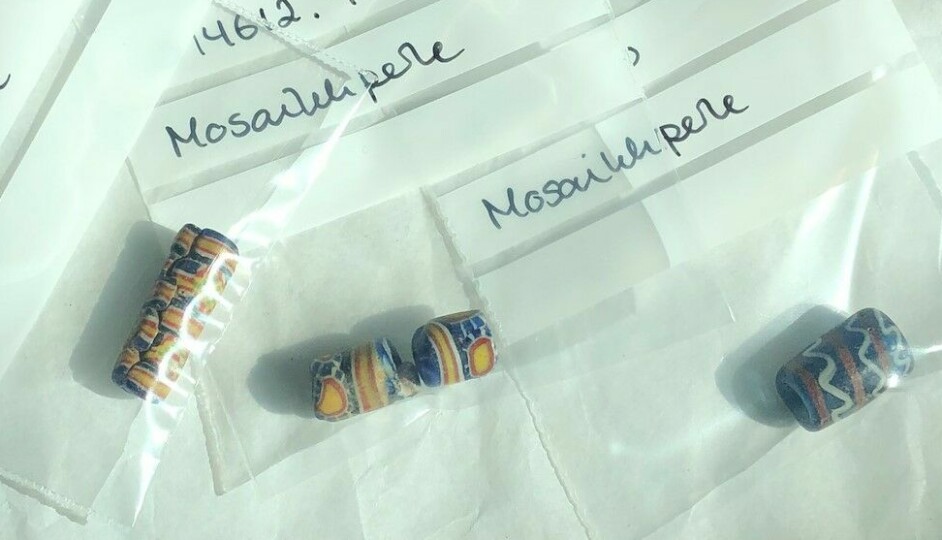

One of the mosaic beads helps date the find to around 850, so early Viking Age.

“Some of these beads are not made in Scandinavia,” says Pedersen.

“Beads were brought from the rest of the world and into the Viking towns of Birka, Hedby, Ribe and Kaupang and further into the countryside. As far as I can see this collection includes beads from Southern Europe and all the way to the Middle East,” she says.

Beads are something that the archaeologists can date quite precisely, and that can often be traced to where in the world they were made.

“Often it seems as though the same type of bead was made for a period of 10-30 years, and then they would change and start making new designs,” Pedersen says.

The collection of beads in the newly discovered necklace may look like a random and disorderly collection to us today. But some 1,200 years ago, this would have been a costly collection built during a lifetime.

The collection handed in to the museum in Stavanger however, also contained three blue glass beads that are different from the rest of the lot: they are from the earlier Iron Age and are several hundred years older than the Viking Age beads.

The woman who owned the jewellery could have inherited them – or they could have belonged to somebody entirely different.

If the jewellery in question was found in a grave, it could be that the older beads were from an older grave in the same spot, and that they just got mixed up when somebody found them.

A wealthy farm owner or an urban crafts producer

The shinier beads in the collection were not of solid gold and silver, they have a thin foil of silver or gold – thus placing their owner at a level below the most powerful in society.

“She’s not from the highest levels of the hierarchy, she’s probably a housewife,” Pedersen says.

“She was certainly wealthy, she had the means to acquire the latest fashion of oval brooches and beads,” she says.

A Viking woman in this position was an active participant in the family economy. The husband and wife in charge of a farm were a team, according to Pedersen.

“She could also have been one of the few who lived in the Viking towns, they would also have dressed like this,” Pedersen says.

An urban woman during the Viking Age who could afford these things most likely administered some sort of crafts production.

“Many of the richest graves with jewellery also contain various equipment for textile production. Perhaps some of the wealthiest women were the ones who administered the production of textiles,” the archaeologist suggests.

“The explanation for the increased craft activity during the Viking Age are the sails of the Viking ships – and who produces the textiles for the sails? Well, that would be the women,” she says.

No context, less information

There will always be a level of uncertainty connected to a find without context such as this.

“In this case, several years have passed between finding the items and handing them in. It’s very commendable that they were now brought in,” says Pedersen.

“We do get a lot of information from finds like this, just not as much as if an archaeologist had been contacted straight away,” she says.

Archaeologist Sørgaard from the University of Stavanger speculates that some people might worry about the consequences of handing finds like this over to the authorities.

“We try to inform them that they don’t have to fear that we will come and upend their entire property,” she assures.

In Norway, finds that are believed to stem from before 1537 are to be reported and delivered to a relevant office of cultural heritage conservation.

------