New discovery of a Viking ship in Norway

A 20-metre-long Viking ship has been discovered using georadar on a mound previously believed to be empty. “This is a spectacular find which sheds light on the earliest Viking kings”, says archaeologist Håkon Reiersen.

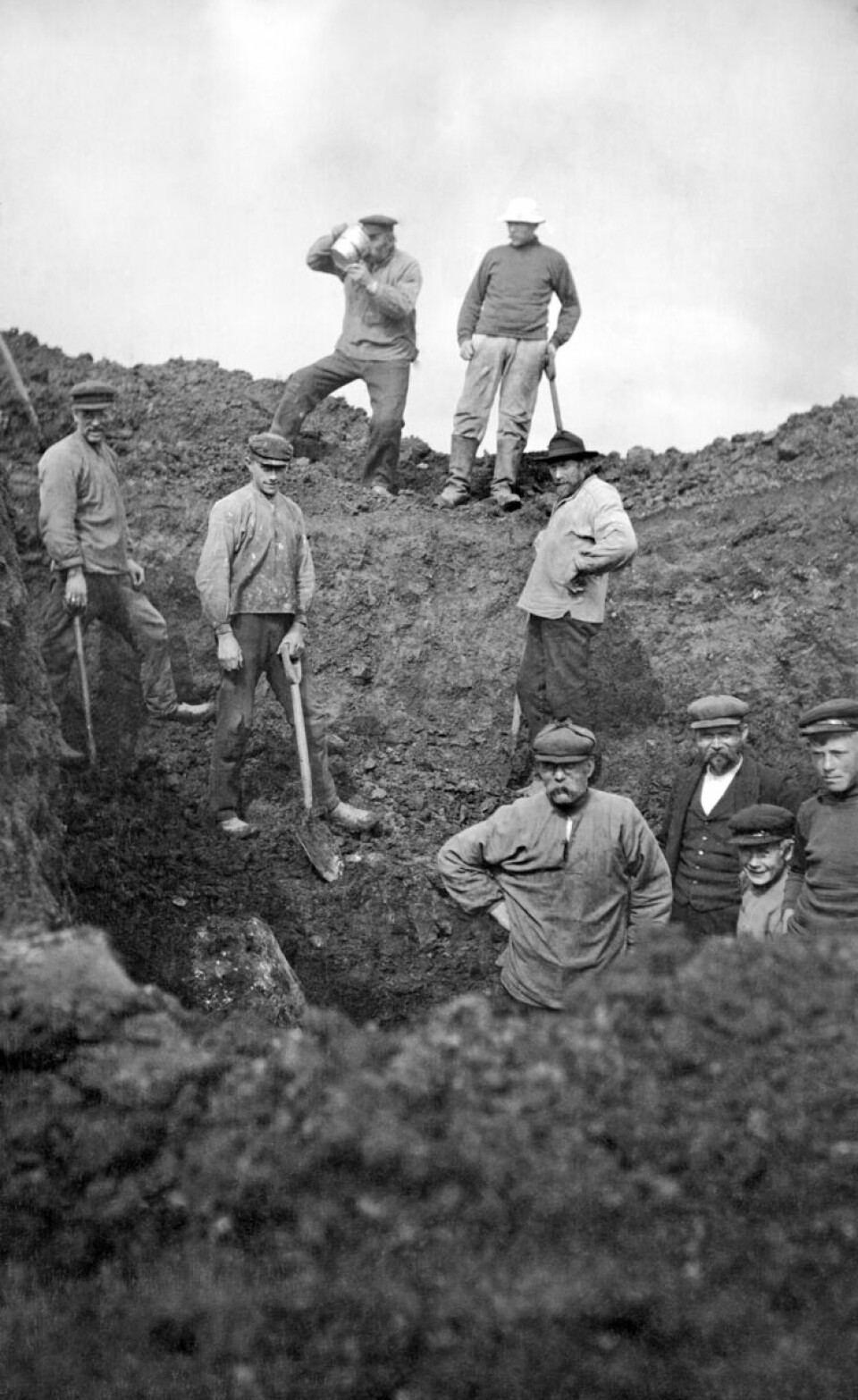

Just over a hundred years ago, the archaeologist Haakon Shetelig was incredibly disappointed when he did not find a Viking ship during an excavation of the Salhushaugen gravemound in Karmøy in Western Norway.

Shetelig had previously excavated a rich Viking ship grave just nearby, where Grønhaugskipet was found, as well as excavated the famous Oseberg ship – the world’s largest and most well-preserved surviving Viking ship – in 1904. At Salshaugen he only found 15 wooden spades and some arrowheads.

“He was incredibly disappointed, and nothing more was done with this mound,” says Håkon Reiersen, an archaeologist at the Museum of Archaeology at the University of Stavanger.

It turns out, however, that Shetelig simply did not dig deep enough.

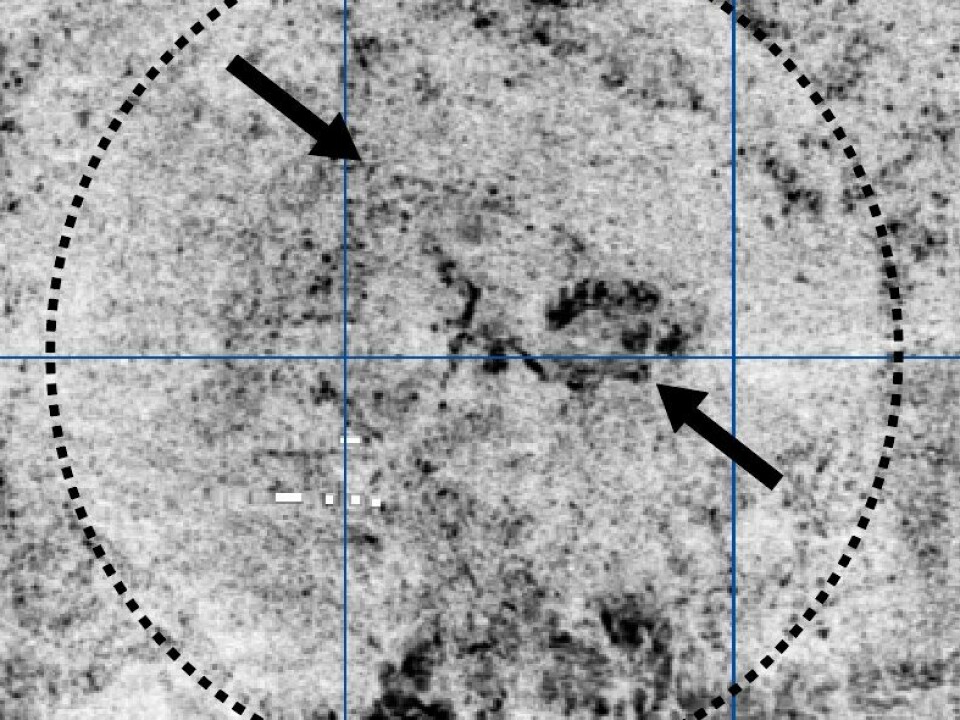

About a year ago, in June 2022, archaeologists decided to search the area using ground-penetrating radar or georadar – a device that uses radio waves to map out what lies below the surface of the ground.

And lo and behold – there was the outline of a Viking ship.

Right in the middle of the mound

At the time, the archaeologists kept the discovery a secret, to finish up with their excavations and explorations and be a bit surer of what they had found.

“We’ve been working on this for a year, so we feel pretty confident about our findings,” says Reiersen, who was project manager for the field work.

Publications are yet to come, but the data from the georadar surveys are quite clear, according to Reiersen.

“The georadar signals clearly show the shape of a 20-metre-long ship. It’s quite wide and reminiscent of the Oseberg ship,” he says.

The Oseberg ship is about 22 metres long and a little over 5 metres wide.

What’s more, the ship-shaped signals are located right in the middle of the mound, exactly where the burial ship would have lain. The likely explanation being that it is in fact the burial ship.

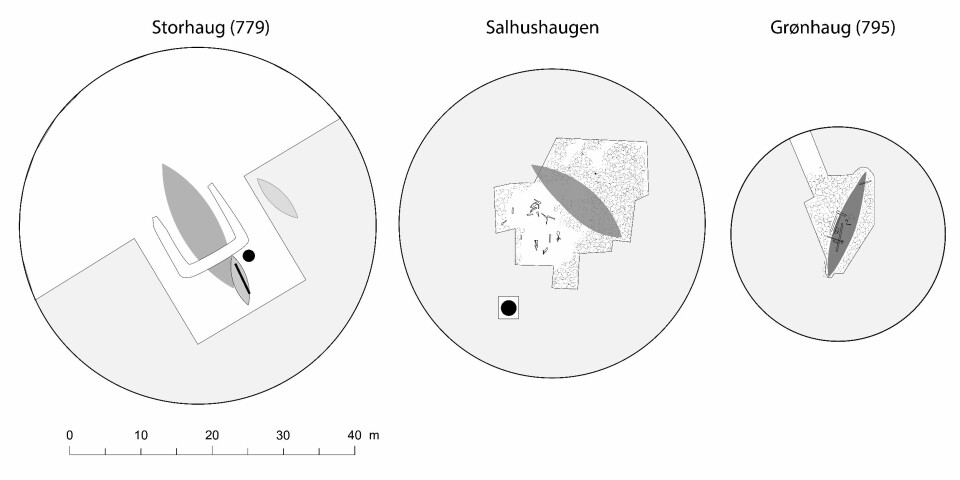

The ship is also reminiscent of yet another Viking ship found on Karmøy in 1886, the Storhaug ship, and finds made in connection to the excavation of this.

“Shetelig found a large circular stone slab in Salhushaugen, which may have been a sort of altar used for sacrifice. A very similar slab was found in the Storhaug mound as well, and this ties the new ship to the Storhaug ship in time,” Reiersen says.

No less than three Viking ships in the same location

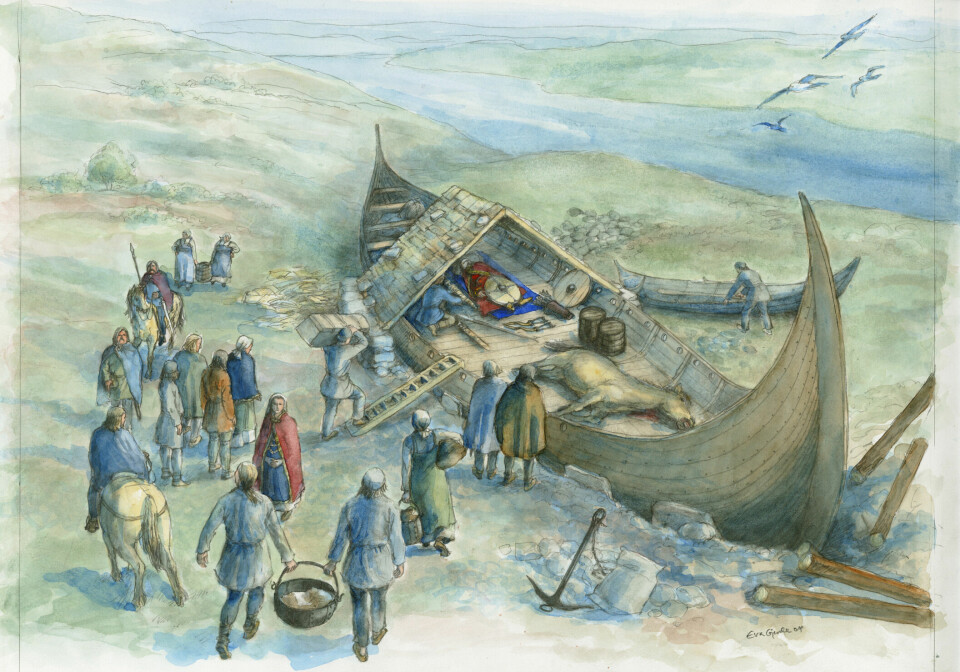

With this most recent find, Karmøy, a historical centre of power for more than 3000 years on the southwestern coast of Norway, can now boast of three Viking ships.

The Storhaug ship is dated to 770 – and was used for a ship burial ten years later.

The Grønhaug ship is dated to 780 – and buried 15 years later.

The most recent addition, the Salhushaug ship is yet to be confirmed and dated, but the archaeologists presume that also this ship is from the late 700s.

The archaeologists are planning on doing a verification excavation, to examine the conditions as well as perhaps get a more certain dating.

“What we have seen so far is just the shape of the ship. When we open up, we may find that not much of the ship is preserved and what remains is merely an imprint,” says Reiersen.

When a possible explorative excavation may happen is uncertain.

Back in the day, decades before Shetelig’s excavation, the Salhushaug mound was around 50 metres in diameter and 5-6 metres tall.

“It was huge! Most of this of course is gone, but there is a plateau left, which is typically the most exciting part of the mound. We think there are still things left to be found there,” Reiersen says.

Home of the first Viking kings

The three Viking ship graves in Karmøy show that this is where the first Viking kings lived, according to Reiersen.

The burials of the more famous Viking ships Oseberg and Gokstad, excavated around 120 years ago, are dated to around 900 for Gokstad, and 834 for Oseberg.

“There is no other constellation of ship burial mounds as large as this,” says Reiersen.

“This is the part of the country where things were happening in the early Viking Age. The Scandinavian ship grave tradition was established here, and then spread to other parts of the country,” he believes.

The regional kings who ruled in this area controlled the ship traffic on the west coast. Ships were forced to sail through the narrow strait of Karmsund along what was known as Nordvegen – the way to the north. Which is also the origins of the name of the country, Norway.

The kings buried in the three Viking ships of Karmøy were a powerful bunch, in a part of Norway where power stood strong for thousands of years. The village of Avaldsnes in Karmøy was home to the Viking King Harald Fairhair, credited with uniting Norway around the year 900.

The first Viking ship with a sail?

“The Storhaug mound is the only Viking Age grave from Norway where we have found a gold arm ring. It wasn’t just anybody who was buried here,” says Reiersen.

Besides finding a new Viking ship, PhD student Massimiliano Ditta has gone through all the finds and the documentation from the Storhaug ship excavation in 1886-87. Using new methods of analysis, he has discovered that what was previously believed to be a rowing ship was in fact a sailing ship.

The keel of the Storhaug ship, as well as what might be parts of the yard from the top of the sail among other things point in this direction. Ditta’s studies have not yet been published, but Reiersen believes his finds will become the new established knowledge about the Storhaug ship.

The Oseberg ship has until now been considered the oldest Viking ship with a sail. If Ditta and Reiersen are correct, this fact will have to be reconsidered.

A magnificent find

“It’s a magnificent find,” says professor and archaeologist Jan Bill. He is curator of the Viking Ship Collection at the Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo.

“Karmøy has always stood out as unusual with two ship burial mounds located in the exact same area, so this third ship just adds to the impression that there is something special going on here,” Bill says.

He also welcomes the research on the Storhaug ship as a possible sailing ship.

“The information we’ve had on this ship has been contradictory, if this new research can bring clarity, then that’s great,” he says.

Bill is however not so certain that the tradition of ship burials starts in Karmøy, citing earlier examples from England and Estonia.

Whether the Storhaug ship is the first Viking ship with sails also remains to be seen, Bill points out – as the Gjellestad Viking ship which was excavated a couple of years ago has yet to be dated and may be from the same time period.

Part of a trend of new Viking ships

Archaeologist Christian Løchsen Rødsrud was project manager for the excavation of the Gjellestad Viking ship in 2020 and 2021. The ship was first discovered using georadar a couple of years earlier. Initial excavations revealed that the ship was in dire straits and needed to be excavated as soon as possible to save the remains.

“This new find is part of a series of new ship finds during recent years,” says Løchsen Rødsrud, adding that not having seen the geophysical photos he can’t say too much about what they possibly show.

Gjellestad was the first ship to be discovered using georadar, according to the archaeologist.

Other Viking ships have also recently been discovered with georadar at Edøy in Western Norway, at Borre in Eastern Norway and possibly also by abundant amounts of rivets at Jarlsberg in the same region.

“Our work seems to have opened up for a new generation of archaeologists who are again focusing on these burial mounds,” he says.

Even though Norwegian archaeologists are discovering remains of Viking ships, there is no guarantee they will be excavated.

According to Løchsen Rødsrud the decision on the ship found in Borre is to leave it until the work on the Gjellestad ship is finished.

“Gjellestad was the first, and the government decided to spend money on it. I don’t want to speculate about the political climate for funding further ship burial excavations at present” he says.

“Since this find is in another part of the country and belongs to a different museum, they might have a strong interest in opening things up so they can get a gist of the conditions, and maybe an option might be funding from the private sector” he adds.

------

This article was updated on 24 April to add the word 'Salhushaugen' to the quote about the stone slab - Shetelig found a stone slab in Salhushaugen, which was similar to one found in Storhaugen. An illustration of the signals from the georadarsurvey was also added.