Archaeologists' most exciting finds:

Teeth marks reveal the everyday lives of ordinary people

The past is filled will regular people, not just kings and queens. It’s essential to remember them, an archaeologist argues.

At the University of Bergen’s museum archives, many forgotten stories reside. Archaeologist Gitte Hansen’s job is to date these hidden treasures.

She helped initiate the Borgund Kaupang project at the University of Bergen.

This project explores the town of Borgundkaupangen in western Norway. Its goal is to find out how the town came into existence, why it disappeared, and also who lived there.

Among a collection of materials, Hansen discovered something remarkable.

Set aside

“I wanted to review the material again to understand what was actually found in the 1950s. Our catalogues describe what was believed to be found back then. In the 1950s, there was limited knowledge about the medieval material culture,” says Hansen.

The material had been set aside for a long time, especially after the Bergen dock fire.

It has not been forgotten, though.

“In the Borgund project, we’re reclassifying all the objects we have identified. Among the 51,000 objects from Borgund, nearly 7,000 are made of leather,” she says.

Learning from leather

Clothing tells us something about the people who wore them. Leather, in particular, can contribute to this story.

“The leather items are quite fascinating. Big shoes indicate big people; tiny shoes indicate small children. I’m interested in the demographic composition of a medieval town. My scientific goal was to examine this material to study the demographics,” says Hansen.

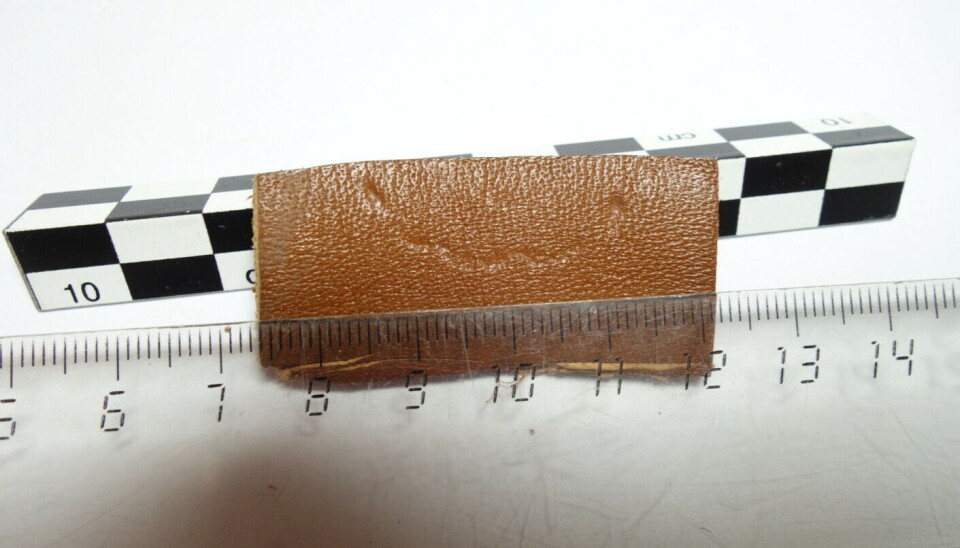

When Hansen reviewed the material, she came across a leather sheath, a holster for storing a knife. Upon closer inspection, she noticed some small marks, which she assumed were bite marks.

To confirm these were indeed bite marks, Hansen enlisted the help of her granddaughter Ronja, 5.

She compared Ronja’s bite marks with those on the sheath, confirming her theory.

Everyday practices

Using teeth as a tool is something many people do and have evidently done for a long time.

The sheath belonged to a small knife, and since it was quite tight, Hansen believes the teeth were used to loosen it from the knife.

“I found this discovery fascinating because it’s something we still do today. The person used their teeth as a tool, just like I do,” she says.

Why did she find this particular discovery so exciting?

Most viewed

“It may not be a discovery that answers the big questions, but I believe it’s important because it’s something familiar to us. It reveals something about humans on a personal level. It's a connection from one person to another,” she says.

Hansen believes there’s also a story behind the sheath that sparks the imagination.

“I get a bit curious about whether I might be able to find out more about the person who used this sheath or this knife. This sheath was found along with many other items from a shoemaker’s workshop,” she says.

Bringing the Middle Ages to life

“I usually say I’m neither a king, queen, nor priest. I’m an ordinary person. I find it more relevant to learn about people who were like most of us,” she says.

Hansen hopes this find can help paint a picture of how people lived in the Middle Ages.

Everyday activities can give us an insight into what life was like in the town.

“I want to peek inside the homes of people in the Middle Ages and see what went on in their daily lives. I think it’s quite human to be curious about how others live, what they think, and the conditions they live under,” she says.

Hansen explains that in their project, they are less focused on the traditional big questions about the town’s origins and development.

“We’re more interested in what kind of lives people had. We want to see the everyday life of those who lived in and visited Borgund,” she says.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Reference:

You can read more about the Borgund Kaupang project on the University of Oslo’s website