A unique medieval boat has been given its own museum in Northern Norway

However, many secrets still lie hidden within the only preserved medieval boat in Norway.

This summer, a special museum opened on the small island of Lovund at the edge of the Helgeland coast.

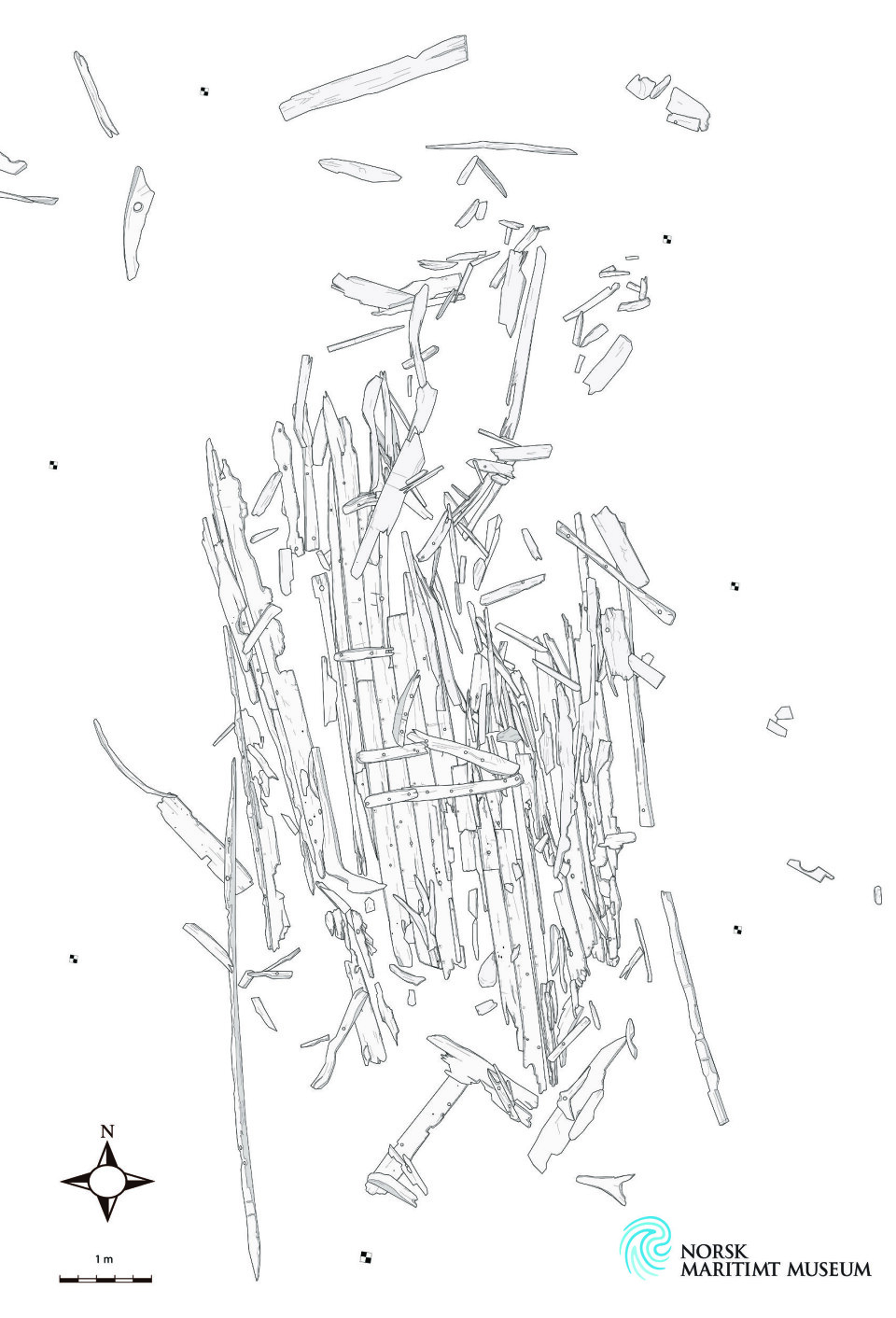

An excavator accidentally uncovered the remains of the ancient boat, which has now been dated to 1460.

The vessel is the only preserved one from the Middle Ages in Northern Norway.

“This is also the only larger medieval vessel currently on display in Norway,” says historian Ann Kristin Klausen.

She is head of collections at Svalbard Museum and has written a book about the over 12-metre-long Lovund boat.

The Norwegian Maritime Museum has been responsible for the excavation and reconstruction of the vessel. The research was led by the Arctic University Museum of Norway.

Significant interest

The boat sparked considerable interest on Lovund when it was found in 1976.

Many questions arose: Who actually used this boat? Why did it sink? And why is it on a small island off the Helgeland coast?

We may never get definitive answers to these questions.

But researchers have worked hard to contextualise the find.

Several items found in the boat provide insight into life and events on board.

In the remains of the boat, they found whetstones, leather shoes, wool textiles, fish bones, and animal bones. The tar in the boat contained traces of plants and animals.

Formation of an interest group

The boat remained at the discovery site until 2017.

In 2015, an interest group was formed. They aimed to have the boat excavated and displayed, in collaboration with archaeological experts.

Bjørnar Olaisen, a former professor and forensic scientist at the University of Oslo, moved back to Lovund in 1997. He has been central to this interest group.

“In 2015, we decided it was time to finally do something about this find. We took on the responsibility of securing the necessary funds,” he says.

Another boat found on the neighbouring island

Two researchers have been particularly central to the excavations and research.

They are Stephen Wickler, archaeologist at UiT the Arctic University of Norway, and Tori Falck, who has been employed at the Norwegian Maritime Museum.

Falck was the project leader for the excavation on Lovund. She has a lot of experience from extensive excavations in Bjørvika in Oslo.

“Only two complete medieval shipwrecks have been found in Northern Norway,” Falck tells sciencenorway.no.

“One is on Lovund, and the other, interestingly enough, is on the neighbouring island group Træna,” he says.

“It’s remarkable that both of these wrecks are located here on the outer coast. Both boats were found in shallow water and were abandoned in a harbour area, so they weren’t shipwrecks.”

Falck believes the main reason the Lovund boat was abandoned in the Middle Ages is due to wear and tear from long-term use.

“The boat’s materials show signs of needing repairs. The vessel has been patched up and sealed with many different materials,” he says.

Still a mystery

There are many mysteries surrounding the Lovund boat.

One of the most puzzling aspects, according to Falck, is that the oak timber boat remained visible to people on Lovund for a long time, without anyone on the island using the wood.

“This is a place almost devoid of trees. A boat made of solid oak is somewhat rare in Northern Norway, where boats are typically made of pine,” she says.

Using dendrochronology (tree-ring dating), researchers found that the wood in the Lovund boat came from oak that grew in Southern Norway.

“The boat was probably also built in Southern Norway,” says Falck.

Used in the stockfish trade?

One theory is that the boat was used in the extensive stockfish trade between Bergen and Northern Norway.

This trading system lasted for many hundreds of years and was crucial for both the coastal population and the people of Bergen. The fish was exported to Europe.

“If you study the later district vessel system and jekt trade, the vessel represents a very early phase in this northern trading activity,” says Falck.

The people of Northern Norway who participated in this trade of stockfish from the north and grain from the south were fisher-farmers.

Or used for local transport?

The boat could also have been used for internal transport, points out Ann Kristin Klausen.

“Lovund is an island with a large puffin colony. There might also have been transport of feathers or meat from the puffins, in addition to fish and other maritime resources,” she says.

Archaeologists and historians have shown great interest in the settlements along the coast of Northern Norway. But until recently, they have paid less attention to the small islands out at sea.

“Several small island communities in Northern Norway exerienced stagnation or depopulation in the post-war period. But they may have played a significant role in society in earlier times,” Klausen believes.

Who owned the boat?

Was it local owners who used the boat to transport their fish?

Or was it people from elsewhere who happened to land and abandon the boat on Lovund?

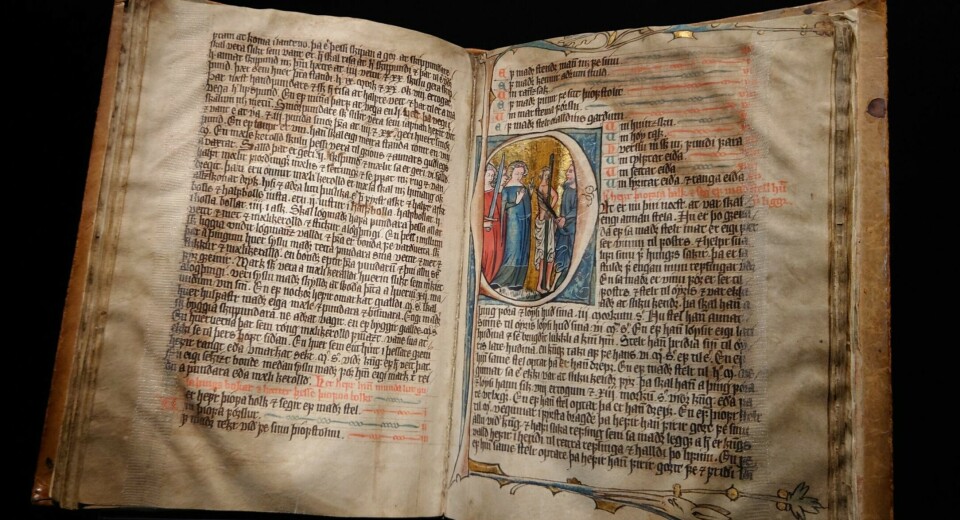

This is just one of many questions that researchers and the local community will probably never get answers to. Written records from this time in Northern Norway are scarce.

Bjørnar Olaisen, who lives on the island, believes there is a good chance the boat had some connection to Lovund.

“Why else would they choose this specific spot to abandon the boat?” he asks.

Why Lovund?

Today, Lovund is a thriving island, in contrast to many other island communities on Helgeland. The northern Norwegian salmon farming industry started here as early as the 1970s.

Ann Kristin Klausen partially attributes the discovery of the boat to the high level of activity on the island.

“Lovund is heavily developed. A lot of commercial activity takes place here,” she says.

Klausen believes there could be more such boats along the outer coast of Northern Norway.

“They might not have been discovered simply because there hasn’t been much development in those areas. Archaeological finds often come to light during construction processes. The Lovund boat was found while excavating material for a road,” she explains.

Marine archaeologist Tori Falck points out another factor:

“When a boat was lost in Northern Norway, it often happened during an accident in rough weather. The boat either sank or was smashed to pieces along the coast in a storm,” she says.

Rarely privately funded

It is very rare in Norway for private individuals to finance archaeological research excavations, conservation, reconstruction, and exhibition in their own building, says Klausen.

She finds it commendable that people choose to invest in this.

“I believe this find will significantly impact the island of Lovund. It provides a connection to the past for the residents here,” she says.

However, she emphasises that the boat also holds national importance.

“The museum opened this summer and has already become an attraction,” she adds.

Primarily for the island

A key condition for Bjørnar Olaisen and other private donors to finance the research excavation was that the boat would remain on Lovund.

For many years, this island has been a popular destination for tourists wanting to experience the coastal nature. The large puffin colony, in particular, attracts many visitors.

But the main reason the locals built a museum for the Lovund boat was not to attract more tourists, according to Olaisen.

“If the Lovund boat gains national interest, that’s great. But we did this primarily for the people of the island,” he says.

Building identity

In much of Norway, the Middle Ages is a period that is poorly documented. This is especially true in Northern Norway, Olaisen points out.

“Now we have something remarkable to show from this era in Northern Norway,” he says.

Like historian Ann Kristin Klausen, he believes this will strengthen the local community’s connection to the past.

“It builds a sense of identity for the place,” he says.

All first graders starting at Lovund school are encouraged to find a pebble around the boat, on which they write their names.

“This creates a visible connection to the museum and their history,” says Olaisen.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no