Why do we love the Vikings so much?

Violent vikings might be the ones we see in movies and on TV, but Vikings are also popular today because they represent a return to our roots and nature, researchers claim.

The drummers from the folk music group bang away at their hand drums and chant along. People go alone, in pairs or as families up to a statue of the Norse god Frøy, associated with virility, peace and good harvest among other things.

At the statue, which includes a huge phallus, the participants at the Midgardsblot festival dip a branch in a bowl of pig blood. They stroke the branch over the statue and say whatever they wish to say to the god, or any other powers. Some also paint themselves or their partner in blood.

They come from all over the world, and they have just participated in a blot – the Viking ritual for sacrifice.

The scene might sound like something out of the history books. But the Midgardsblot festival in Norway is a modern-day creation, started in 2014 as part of the Norwegian constitutional jubilee that year.

“It appears in every way as a religious ritual,” writes Anne Kalvig, religious scholar and professor at the University of Stavanger, in a popular science article soon to be published in the journal Kirke og Kultur, Church and Culture (only available in Norwegian).

Through blood and chanting and the sharing of these actions, differences are dissolved, community is created and the tone for the festival is set. “Welcome home!” as the banner across the entrance to the festival reads.

Everybody loves Vikings

The festival Midgardsblot attracts between 5000-6000 people from all over the world to the historical site of Borrehaugene. A fairly large portion of them are Americans. Among real Viking graves, participants enjoy what is called extreme metal and folk music, and a popular version of living as Vikings, where Vikings once lived.

The festival is one of many popular culture Viking phenomena of recent years, according to Kalvig and the research group behind the project Back to blood. They want to find out why the Vikings are so popular today. And what sort of Viking and Norse past which is embraced and communicated.

The project spans everything from History Channel’s popular show Vikings, and the Norwegian Viking comedy Norsemen to the video game Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla. The researchers will look at Viking festivals and markets, Viking museums and exhibitions, online communities, re-enactment communities and martial arts enthusiasts. They plan on investigating modern heathens and pagans, some who belong to the religion of Asatru, a modern-day version of Norse mythology.

“What we have seen is that Vikings and the Norse past has become popularized in all sorts of possible and impossible contexts, and we believe this is worth examining. Where is the interest coming from, not just here at home in Norway but also globally?” Kalvig asks.

“What we’re talking about here is a fairly limited period of time, within a geographically limited area – but which can obviously be used to nourish a lot of different subjects that people find interesting and fascinating and important on different levels,” the professor says.

Sustainability and nature, not violence and terrorism

The Midgardsblot festival has been held at the Midgard Viking Centre at Borre since 2015. Professor Kalvig has participated twice as part of her research project.

“I thought it was quite scary at first, to go to a metal festival. But I quite like it. The crowd is very friendly and inclusive, and there is a clear policy of diversity,” she says.

Kalvig finds it fascinating that people from all over the world - with no connection to Norway or Vikings whatsoever - are drawn to this very small and particular festival.

“The celebration of a Norse past is supposed to lead us to a celebration of all our histories and identities in a sort of common human identity project, which again is to connect us to nature and to the larger context of being human. At least that is how I understand the project and the intention of the festival,” she says.

In the news, this positive view of Viking inspired actions is hardly dominating. White supremacists, Nazis, and right-wing extremists have embraced and used various Viking symbols and Norse mythology in terror attacks in recent years causing death and destruction. When a pro-Trump mob stormed the US Capitol earlier this year, one of the photos shared around the world was that of the so-called QAnon shaman, Jake Angeli, sporting Viking symbolism in his tattoos.

But Kalvig and her team are certain that we are missing something if we let this view dominate in our understanding of the popularity of Vikings. For a lot of people, they claim, an interest in Vikings and Norse mythology represents a return to nature and more “green” ideas of how to live life.

“In our research group we have identified that re-thinking and re-imagining our relation to nature, a return to our “roots” and finding our way out of today’s ecological crisis by searching in old tracks, is important for people’s enthusiasm and interest for Vikings and the Norse past,” Kalvig writes in the unpublished article on the topic.

Modern-day people are looking to the Vikings in order to explore issues of sustainability, identity and citizenship, the researchers behind the Back to blood project believe.

One modern-day Viking gives up

Still, the way Vikings and Norse mythology is being used by extremists casts a shadow upon those who try to explore these topics in a more positive direction.

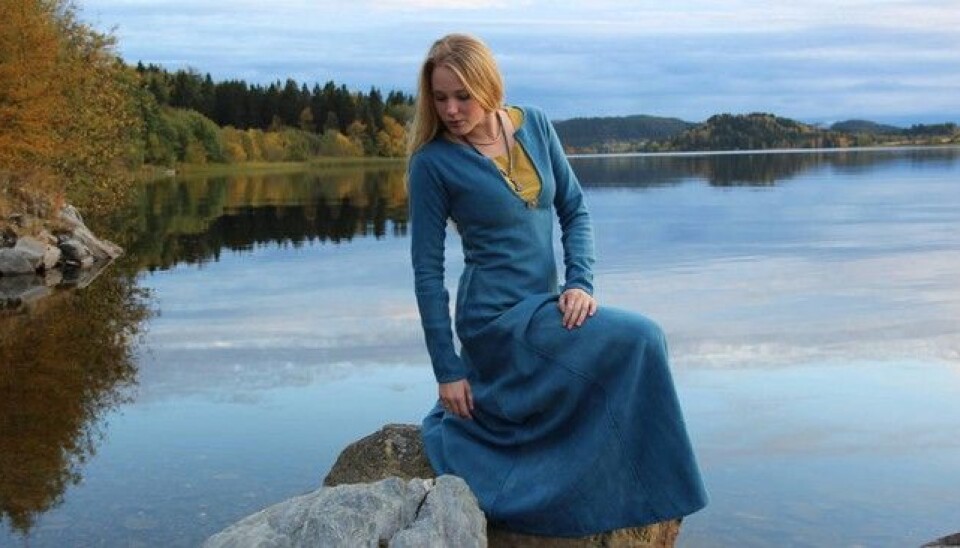

Earlier this year, Ingrid Galadriel Aune Falch who has been active within Viking re-enactment in Norway, announced on her blog under the heading The beast I can’t control that she was going to quit being a Viking.

After struggling to get her photos taken down from extremist sites connecting pictures of herself to slogans like "Europe for whites" and "Immigrants go home", and educating people on the diversity of those interested in Viking re-enactment, she finally folded.

“I can no longer claim that the Viking community is free from right wing extremist attitudes. Too much crap has weaseled its way in”, she said to the national broadcaster NRK (link in Norwegian).

Falch tells NRK that the re-enactment community has grown considerably over the past years, both at home and abroad. She believes there are around 30 active Viking groups in Norway at the moment.

According to Falch, a lot of people in the Viking communities are trying to be responsible in tackling right-wing extremism within. Events are screened and people who should not be there are dismissed. But she believes there's a need for a greater discussion on how Norwegian culture is conveyed to the public and tourists.

“We have to realize that our cultural heritage and history has become political. Most people lack competencies on this”, she says.

But she herself is done defending.

“I’m being put in the same category as extremists. I’m tired of it”, she says to NRK.

Speaking out against misinterpretations

The extent to which right-wing activists embrace and use elements from the Vikings and Norse Mythology, has even led to a heathen "fatwa" of sorts. Declaration 127 from 2017 was signed by 180 heathen organisations from all over the world, based on the 127th poem in the old Norse poem Havamal:

“When you see misdeeds, speak out against them, and give your enemies no frið”

“The reaction from the progressive Asatru groups is to condemn racism and fascism, while at the same time being very clear on their own stance on being pro lgbt rights, supportive of Black Lives Matter, for equality and against discrimination,” researcher Jane Skjoldli says.

As part of the research group, her project is to analyze popular culture representations of Vikings, and interview religious groups such as Asatru and other modern heathens about their views on these cultural products and events.

When is it politics, when is it not?

Anne Kalvig confirms that also the Midgardsblot festival has had trouble with "people who did not have the same pluralistic values as they do."

“They have encountered these problems, but they believe they have found good ways of handling them,” she says.

Already during the first edition of the festival in 2015, the topic was tackled during public debates at the festival. Runa Strindin, head of the festival, said to newspaper Dagsavisen that they wished to address the elephant in the room, defined as “the abuse of Viking history throughout the centuries.”

“The festival is about culture and people meeting, not politics. But this is a hard line to balance of course, because when do politics start and end?” Kalvig asks.

Generally, the professor believes there are differences in how people perceive various symbols and their use – for instance the swastika, used by Nazis, which is a historic symbol that may be found in historically correct garments.

“Americans will usually have a stronger reaction to this than people in the Nordic countries, despite the fact that Norway for instance was occupied,” Kalvig says.

Less archaeological finds, but the most attention

While some pretend to be Vikings at festivals and fairs, archaeologists in Norway have during the past year been digging out an actual real Viking ship.

Project manager Christian Løchsen Rødsrud has been in the archaeological digging business for 20 years. The Gjellestadship is by far the most special thing he has ever been a part of unearthing. It is also by far the dig which has received the most attention – not just locally or in Norway, but worldwide.

The experienced archaeologist has spoken about the dilapidated ship found in the Eastern part of Norway on TV in Japan and Brazil. Documentaries have been or are being made, last summer NRK broadcast a live minute-by-minute dig for an entire week, which included a visit from Norwegian actor Kristofer Hivju – also known as Tormund Giantsbane from Game of Thrones.

“There’s something about the Viking Age,” says Løchsen Rødsrud.

“It is somehow more special than other archaeology, which in a way is odd, as we dig out far more stuff from other time periods – but it’s always the findings from the Viking Age which receive the most attention”, he says.

The Viking Age spans a short period of time, from around 800-1050 AD.

Løchsen Rødsrud believes the Sagas are part of the reason why the Viking Age captures people’s attention.

“Everybody knows these Sagas and relate to them in different ways. And then the history is taught in schools, not just in Norway but also other countries. It’s an important part of British history for instance, due to the invasions but also the immigration, which is not communicated well enough,” he says.

A lot of the writings about Vikings are from France and Britain, where the tales tell of plunder and rape. But large parts of the Viking army also ended up settling down.

“That these events were documented is not odd, but I do believe that the level as to which violence was part of Viking culture is out of proportion based on these accounts,” he says.

The fact that Vikings were buried with weapons has also contributed to a focus on weapons and war, Løchsen Rødsrud believes. And as well the fact that those who were buried - and whose graves we have found - were of the wealthier sort. The everyday Viking was not so important to write about and didn’t make it into the Sagas.

More than just violence

Vikings have been popular for as long as Løchsen Rødsrud has been an archaeologist. And during other times in history.

"If you go back a hundred years, Wagner had composed the famous Opera Der Ring des Nibelungen, partly based on Nordic sagas. Carl Emil Doepler created some fantastic costumes for the staging of this musical masterpiece at the Bayreuther Festspiele in 1876 with Vikings wearing horned helmets. And the horn clad Viking has survived in popular culture to this day, despite there never having been a finding of a Viking helmet with horns," he points out.

But he confirms that Vikings seem to have had an upswing in popularity in recent years with multiple new popular culture products, museums and cultural centres, re-enactment groups and so on.

Although extremists who embrace and use Vikings to justify or perpetrate violence are quite far away from Løchsen Rødsrud’s everyday working life, he is aware that things he says can be misunderstood and misused.

“We have to be careful in our statements, so things don’t come out wrong,” he says.

Violence is of course a part of the story, but it is also just that, one part. The Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo is in the process of building a new Viking Age museum to house among others the great ships Gokstad and Oseberg, and Løchsen Rødsrud is part of the advisory group. If all goes as planned, the doors to a grand new exhibition will open in 2025.

“With this museum we wish to tell the whole story,” the archaeologist says.

“Not just the part about the violence.”