Here’s what archaeologists found in 2024:

Child graves, silver treasure from the Viking Age, and perhaps Norway's first stone church

The past year has been marked by fewer excavations compared to previous years. But archaeologists have still made some great discoveries. Here is 2024's top list.

'This year is a bad year for archaeology,' the magazine Forskerforum wrote in early December (link in Norwegian).

Norway’s weaker economy means less development, which in turn means fewer excavations.

The Norwegian Archaeology Meeting, an interest group for archaeologists and people who are interested in the subject, also had fewer finds reported to their conference than before, leader Ingar Mørkestøl Gundersen told sciencenorway.no.

And yet, excavations have taken place. And discoveries have made headlines. Some finds from previous years have become more interesting after analyses have been published.

Science Norway has asked archaeologists and the country's university museums to list the most remarkable finds of the past year. Here is what they answered, in no particular order.

Children's graves in Østfold

Archaeologists initially thought they were going to examine some settlements from the Stone Age at a quarry outside Fredrikstad in southeastern Norway.

But then they found a whole lot of stone circles measuring between one and two and a half metres in diameter. These were graves, as many as 41, with cremated remains in the middle.

The burial site was uncovered in 2023, but it was only in 2024 that archaeologists learned more about who was buried there. Analyses showed that most of the graves contained the remains of young children. 16 of those buried were newborns, while others were between three and six years old.

“What's special here is that the children have their own burial site. We know of very few similar finds,” Guro Fossum, archaeologist at the Museum of Cultural History and head of the excavation, told sciencenorway.no.

The archaeologists had not expected to find a burial site, and certainly not a children's burial ground.

“This is an important discovery in many ways,” says Marianne Moen from the Museum of Cultural History.

“When it was uncovered, we immediately knew we were faced with something special, and when the analyses later revealed that almost exclusively children were buried at the site, it emphasised how unique it is. It immediately raises questions and evokes emotions among both archaeologists and the public, highlighting archaeology's relevance for many in today's society,” she says.

The graves date from between 800 and 200 BCE.

Many were upset that the children's burial site was removed after the excavation, and there was debate over the decision in local newspaper Fredrikstad Blad (link in Norwegian).

Silver treasure from the Viking Age

On a mountain slope in southern Norway, a farmer was preparing a new tractor road. Archaeologists were brought in to survey the area before the road was built, to see if there was anything worth preserving.

There was.

Because here, it turned out, there was a large and powerful Viking farm in the 900s.

And under what was once the house of the Vikings’ thralls, archaeologists found nothing less than buried silver treasure.

Four large silver arm rings with unique decorations were hidden about 20 centimetres below the ground.

“This is undoubtedly the most significant event of my career,” said Volker Demuth from the Museum of Archaeology in Stavanger.

Valuable objects like these are most often found in fields that have been ploughed. What makes the Viking treasure in Årdal extra special is that it lies exactly where someone deliberately hid it over 1,000 years ago. Perhaps because they had to flee their farm?

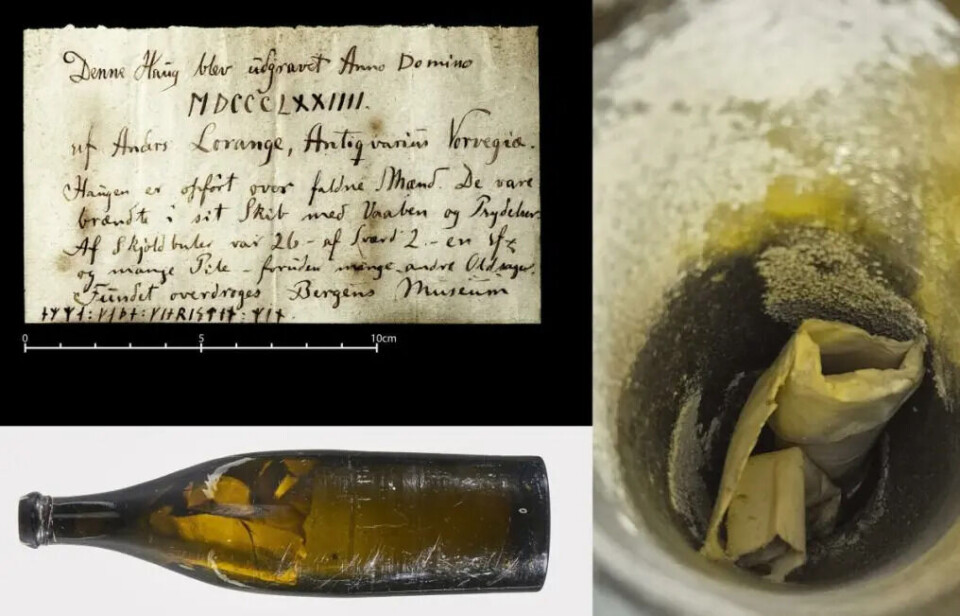

Myklebust burial mound and the message in a bottle from the past

Towards the end of the year, the excavation of the Myklebust burial mound in Nordfjordeid, western Norway, made headlines.

We knew a ship was located here. Archaeological pioneer Anders Lorange excavated this site 150 years ago, uncovering traces of what many speculate could be Norway's largest Viking ship.

Around a quarter of the mound has been excavated, while the remainder will stay untouched – serving as a key part of Norway's effort to include its Viking Age heritage on UNESCO's World Heritage List.

Perhaps we will eventually learn more about the actual size of the ship when archaeologists start analysing what they have now retrieved.

“These rivets will give us crucial information about the type of ship it was, its length, and what function it served. They are key a new understanding of this ship, in which a chieftain was buried over 1,200 years ago,” Morten Ramstad, project leader for the excavation and head of the University of Bergen's Section for Cultural Heritage Management, told sciencenorway.no.

And then the archaeologists found something else: A 150-year-old message in a bottle from archaeologist Lorange. He forgot to write about some of the most important findings but remembered to pay tribute to his sweetheart.

The find was voted the find of the year by Norwegian archaeologists during the Norwegian Archaeological Meeting.

Three wealthy women's graves from the Viking Age

Findings from metal detectorists led to excavations at the Skumsnes farm in Fitjar, western Norway.

Here too, archaeologists uncovered a burial ground. There may be as many as 20 graves. Three of them were excavated this autumn and belonged to women who lived here during the early Viking Age, in the first half of the 800s.

The archaeologists found beautiful jewellery, rare coins, and objects related to textile production.

“It's remarkable to find a burial ground with such well-preserved artefacts,” archaeologist Søren Diinhoff from the University Museum of Bergen told sciencenorway.no.

Morten Ramstad describes the finds in the three women's graves as spectacular, emphasising that the graves were not visible on the surface.

“This highlights that valuable objects reflecting wealth, power, and extensive contact networks are not only found in large burial mounds but also in less prominent graves," he says.

“The discovery at Skumsnes shows connections to Denmark, England, Ireland, and as far south as the Carolingian Empire in present-day France. This provides insight into social and economic conditions during the Viking Age from areas of western Norway where we previously had limited knowledge,” he adds.

The man in the well

According to Sverris Saga, a man was thrown into the well at Sverresborg in Trondheim in 1197.

The Baglers were said to have done this to poison the drinking water of the Birkebeiner.

The Baglers and Birkebeiners were two rival factions in medieval Norway during the late 12th and early 13th centuries. They fought in a series of civil wars for control over the Norwegian throne.

In 1938, a skeleton was discovered in that very well.

It was retrieved in 2016.

Nevertheless, a scientific article with the results of the analyses of the skeleton was not published in the journal iScience before 2024.

"It's not often one gets the opportunity to compare physical remains from archaeological excavations with specific individuals from saga stories," said Anna Petersén from the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU), project manager for the excavation.

So, who was the man?

He was in his late 30s when he died and was likely between 175 and 180 centimetres tall. This was a considerable height for his time, according to the archaeologists, and may indicate that he had good living conditions during his upbringing.

He had a prominent nose, a strong forehead, back problems, and lung disease.

DNA analyses from a tooth revealed that he was blonde, blue-eyed, and from Agder.

Was he not a Birkebeiner after all, then, as people have believed? Or were there Birkebeiners who were not from Trøndelag? Maybe he was just a stonemason at the castle? A random victim? The speculation continues.

1,000-year-old farmstead in Nordland

Archaeologist Stine Grøvdal Melsæther discovered this farmstead on her computer while studying maps of the area for a new power line in Alsvåg, Øksnes municipality, Nordland.

“A short distance from the route we were working on, I noticed something that stood out from the surrounding natural terrain. I could see structures that looked like house foundations arranged in a circular formation on a small hill,” Melsæther told NRK, the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation.

It turned out to be a farmstead from the Iron Age. Archaeologists believe it was a place where people gathered to do important things, possibly a site where important decisions were made in Iron Age society.

The newly discovered farmstead consists of eight house foundations and 20 cooking pits. Archaeologists have taken two soil samples, but the site will otherwise be left undisturbed. Dating from the charcoal samples indicates that the farm complex was most likely in use during the period 500-600 CE.

Around 30 farm complexes have been found in Norway, 12 of them in Nordland, according to NRK.

Norway's first stone church on Selje?

The island of Selja in Stad municipality, western Norway, was once one of the oldest and most important holy places during the Middle Ages.

Archaeologists have been excavating and studying building remains here since the 1800s.

According to legend, Saint Sunniva washed ashore here sometime in the late 900s and died a martyr's death in a cave. Olav Tryggvasson is said to have found her remains in 996 and built a church in her honour.

However, the ruins of the Sunniva Church have been dated to 1068. However, new research from 2024 revealed an older stone church beneath the Sunniva Church, featuring characteristics typical of Anglo-Saxon building traditions.

"The building must be considered one of the first stone constructions in the country – and perhaps the first stone church!" NIKU wrote in a report about the discovery (link in Norwegian).

It is not yet possible to date the newly discovered church to a specific year or decade.

However, NIKU speculates in their article that it may trace back to Olav Tryggvasson and Olav Haraldsson's experiences in Anglo-Saxon England.

“The only comment I have right now is simply wow. If this turns out to be true, it's absolutely amazing,” Anne Irene Risøy, professor at the University of South-Eastern Norway, told NRK.

“The dating of this building is still uncertain. It could be in the Anglo-Saxon style, as has been suggested,” said Professor Visa Aleksis Immonen from the University of Bergen.

"This aligns well with what we know about early Christianity in Norway. But it also shows that there is still much to research when it comes to Selja," he said.

Two beautiful gold rings from metal detecting

Before 2010, fewer than 100 finds from private individuals were reported to the Museum of Cultural History each year. In 2020, the museum received 1,300 finds from Innlandet county alone. That year, they received just over 3,000 finds in total, which remains a record.

Metal detectorists assist archaeologists in excavations, and their discoveries often lead to major excavations.

In 2024, metal detector finds were given their own exhibition for the first time at the Museum of Cultural History. When sciencenorway.no asked which discoveries they thought should be on the list of the year's top finds, the museum submitted photos of two beautiful gold rings.

The first gold ring is likely from the Migration Period, approximately 400–550 CE. It was found in Bamble municipality. It may have been used as a finger ring or a payment ring. The ring weighs around 46 grams.

The second is a gold finger ring with an amethyst stone. It is from the Middle Ages and was found in Stange municipality in Innlandet county.

Both rings are well-preserved, and although gold objects are found regularly, they are not common. Medieval finger rings with preserved and intact gemstones are particularly rare.

These types of rings are already known to archaeologists, making them relatively easy to date, even if they know nothing more about the place where they were found.

———

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Related content:

Most viewed

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.