Was the Oseberg Viking wagon drivable? New methods are constantly uncovering new details about Norway's oldest vehicle

The wagon is the only one of its kind from Norway’s Viking Age, but the wood is dry and brittle. Since 1904, it has been documented with the best technology available.

The Swedish archaeologist Gabriel Gustafson led the excavation of the Oseberg ship. He kept a diary about the ship and the objects. In it, he worries about the responsibility he has taken on and about arguing with the landowner.

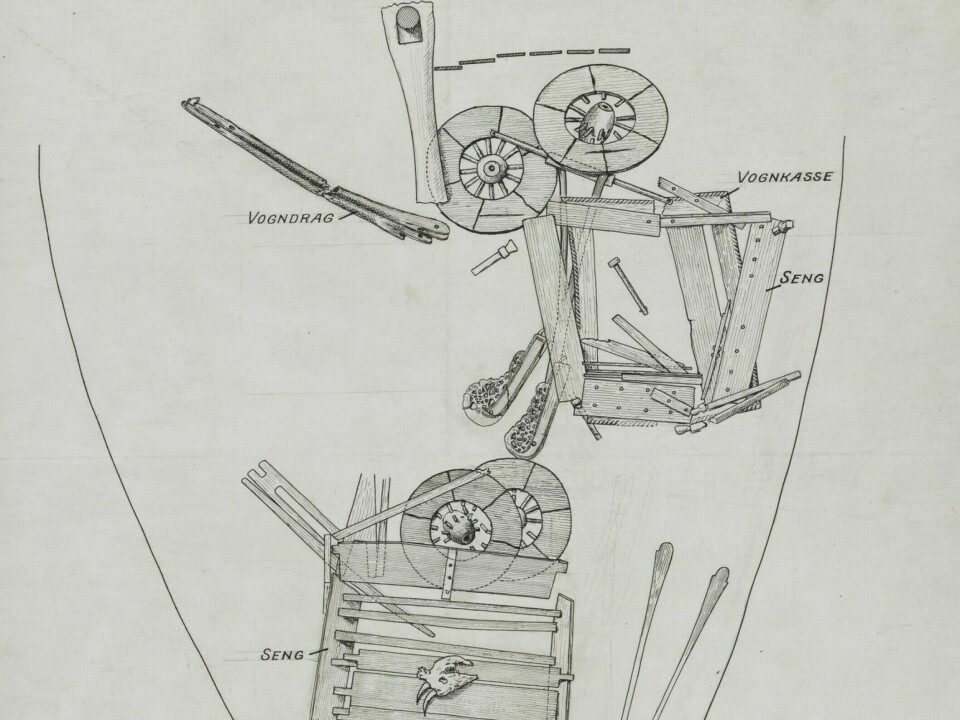

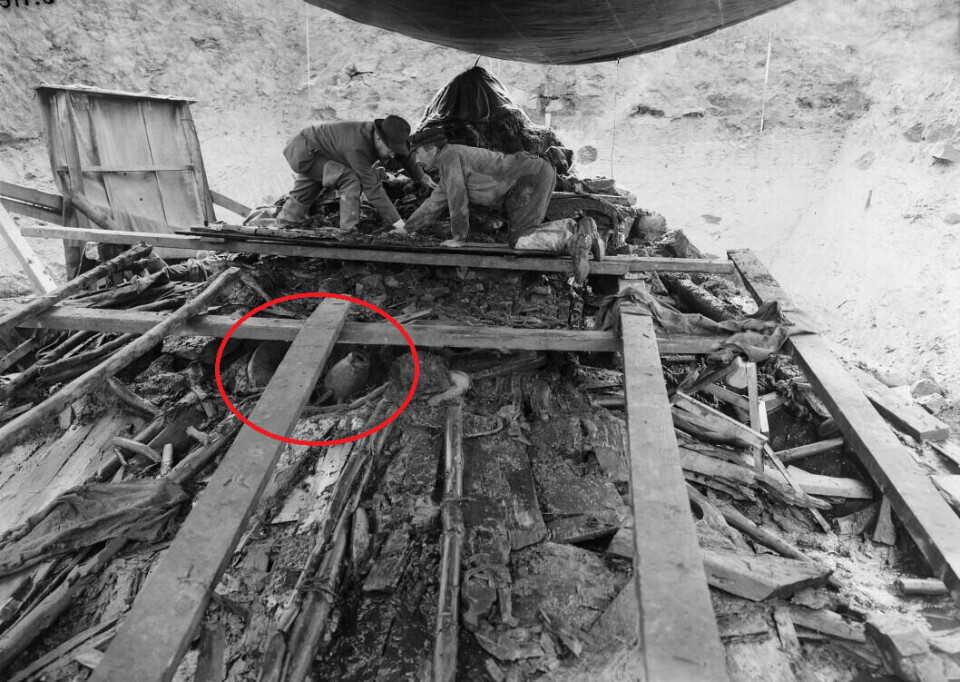

Gustafson and his assistant logged and drew what they found: pieces of wood, sticks, bones, ropes, and metal. Everything was covered in mud. Most of it was in a thousand pieces. The wood was soft and brittle.

It was important to document the objects exactly where they were found. The archaeologists were not certain that everything would survive the trip to Norway's capital, Oslo.

They recorded which parts they thought belonged to which objects, the dimensions, decorations, and the type of wood. They also made sketches.

On 4 September 1904, they found wheels, shafts, and parts that they realised belonged to a wagon.

Someone drew a quick sketch of the chassis. This may be the first documentation of the Oseberg wagon.

The only one of its kind

The Oseberg wagon is the only wagon from the Viking Age found in Norway. It was not new when it was placed in the grave in 834, but was made before the year 800. The wagon is made of beech and oak and is about two metres long and one metre wide. The wagon box, which sits loosely on the chassis, is decorated with men's heads and people fighting snakes and strange animals.

The sketches from the excavation were drawn and published in two large volumes on the Oseberg find.

Two artists were also hired for the excavation, as there were still traces of paint on some of the items. They made drawings and watercolours of decorated bedposts, vessels, and figures.

This turned out to be a sensible decision.

The old paint was attempted to be saved, but it did not survive the conservation of the wood.

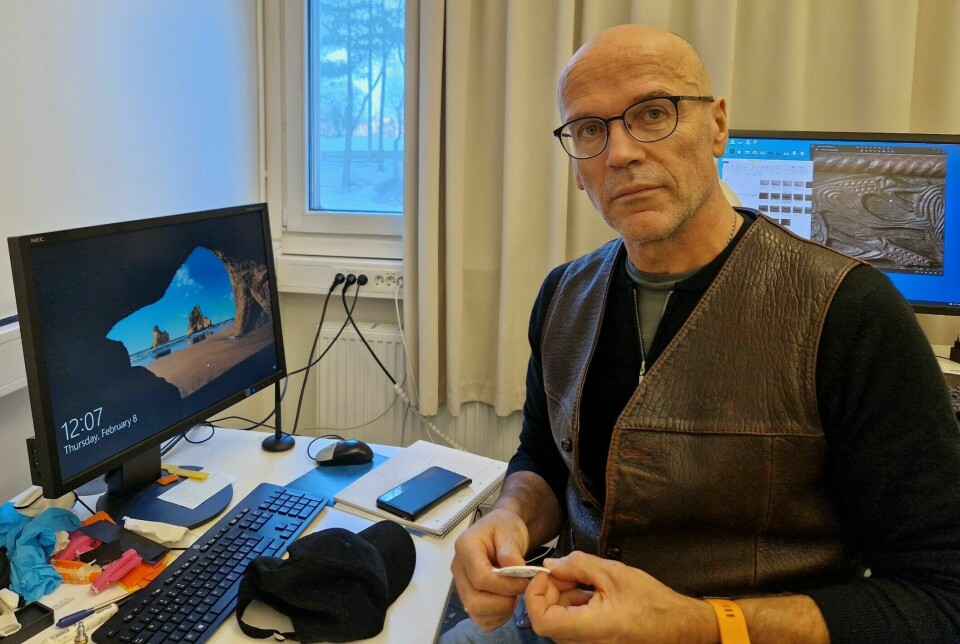

“But it was expensive to hire artists,” says Bjarte Aarseth, a senior engineer at the Museum of Cultural History at the University of Oslo.

It was just as expensive to take photos in 1904.

“That’s why there are hardly any photos of the wagon where it lay in the mud,” Aarseth says. He works with wood carving and scanning at the museum.

The entire Oseberg wagon has now been scanned. But it has been depicted and copied in many other ways between 1904 and today. Here are some of them:

Made it straighter and nicer

Once all the pieces of the ship, wagons, sleds, vessels, beds, buckets, and everything else were excavated, they eventually ended up in the collection of Norwegian antiquities in Oslo.

Then the work began solving the big puzzle of getting the right pieces in the right place. And the old wood was restored. That took several years. But in the end, the wagon was pieced back together.

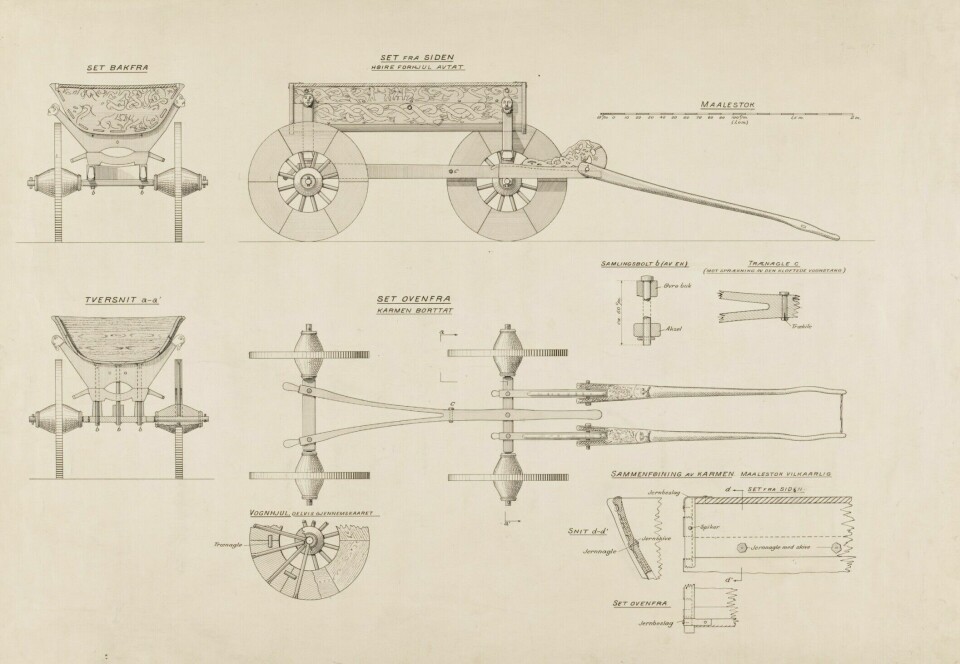

The draftsmen at the museum created a drawing which shows the parts both seperately and when assembled.

“This drawing represents an idealised image. Errors and defects on the wagon have been corrected," says Aarseth.

For example, one of the trestles is older

than the rest of the wagon. It didn't quite fit in, while the other fit

perfectly. In the drawing, the trestles are exactly the same.

“The scale used is also very rough,” he says.

This has been a problem for people who have tried to recreate the wagon.

“Many people have made copies of the wagon, including people in Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Washington. They have used the wagon for parades, but they often look strange,” says Aarseth.

Eventually, the wagon was documented through black-and-white photographs. The photos show details and how the wagon is put together. However, the rich luster of the wood does not come through, nor do all the details.

Created backups

To bring out symbols, patterns, and figures, the museum also used another method:

“They took small pieces of paper, like old-fashioned tracing paper, which they moistened and placed over various parts. They then removed the paper and drew the pattern that was left behind. The problem was that the paper stuck to the wood,” Aarseth says.

As early as 1906, woodcarvers were hired to make copies of the objects in the grave. They were a kind of safety measure in case the originals were destroyed.

Bjarte Aarseth was hired as an apprentice at the woodcarving workshop in 1983. He spent three years carving a copy of the Oseberg wagon, among other tasks.

“They're backups,” he says.

And now, photographs have increasingly better resolution.

Below is the corner of the wagon box. This is a section of a high-resolution image. You can see and zoom in on the photo itself here.

As brittle as crispbread

Eventually, it became clear that the methods they had used to preserve the wood 80 years earlier had serious side effects.

The ship and the objects had been lying in wet blue clay for 1,000 years. When the wet wood saw the light of day in 1904, Gabriel Gustafson had to prevent it from drying out. He kept the objects in water while he consulted with other museums and experimented on his own.

Gustafson chose to bathe the wood in a chemical substance called alum. It was perhaps the best choice in 1904, but it resulted in the old objects being stuffed full of degrading acid.

Within a few decades, the wood became as brittle as crispbread.

In 2013, Bjarne Aarseth started measuring the objects using a 3D scanner, special camera, and PC. At that time, it became even more important to document every single centimetre of the great burial find, in case they crumbled away and were lost forever.

This type of scanning does not go quickly. Small sticky notes, rulers, and crosses are placed around or on the object, to give exact measurements. The camera takes pictures with a resolution down to one hundredth of a millimetre.

“If you imagine a square millimetre, that will get 1,900 dots. Often even more,” he says.

Precise measurements

Researchers have now obtained precise measurements, allowing them to monitor changes in the wood. The camera and scanner do not damage the fragile objects.

“Precise measurements are also extremely important for those creating the new exhibitions,” Aarseth says.

He has finished scanning the Oseberg wagon. All details can be zoomed in on so viewers can examine the smallest detail.

The video below shows the undercarriage of the wagon being assembled piece by piece – just like the original. The colours are turned on and off to show the process.

(Video by Bjarte Aarseth, Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo)

Aarseth is deeply impressed by the Vikings' techniques.

“Every part of the wheel is made with the most suitable type of wood. The beech in the rim was soaked in water before spokes made of oak, which were dried, were added. This shrinks the rim around the spokes. The rim, spokes, and the hub are locked together as a structure, which is incredibly strong,” Aarseth says.

They selected the finest specimens of wood, and treated them so that the parts fit together seamlessly without the need for rivets or nails.

“This is high technology. It's clear that they knew this craft,” says Aarseth.

Decorative or for use?

Archaeologists quickly determined that the wagon was purely for decoration. The three-volume book on the Oseberg find says that the wagon is not suitable for travelling long distances. Furthermore, there were no roads at that time.

Most viewed

No content

It was either a temple wagon for carrying images of gods or a wagon the queen used to display herself to people during religious festivals, according to the book.

One of the arguments used to support the idea that the wagon was not for daily use is that it cannot turn.

But Aarseth does not agree. He has put the parts together digitally and believes that it was definitely both drivable and could turn.

He is not the only one. A similar wagon was found in a Swedish grave, and the archaeologists believe that it had been in use there. The wagon box could be easily removed and loaded onto a boat.

In the book På hjul i Norge (On wheels in Norway) from 1971, the Oseberg wagon is declared Norway's oldest vehicle. The authors, one of whom is a civil engineer and director of the Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology, believed that the wagon could navigate many routes in Norway.

Unknown symbol

The scanned Oseberg wagon allows us to determine who is correct.

We can rebuild using exact measurements or simply 3D print a small replica.

“People can print out the parts and assemble them into a complete wagon,” Aarseth says.

The extremely high resolution scans also reveal new details in the decorations.

Recently, Aarseth found a decoration on the chest of a carved man on the wagon box.

“I called a conservator and asked if he had seen that the man had a symbol on his chest. But he had never noticed it before,” he says.

3D scanning offers new opportunities for researchers and the public alike.

The new Viking Age museum will open in two years; it is currently closed for renovation.

For those who live too far away or want to delve into every detail, scanning has made the ship and the objects more accessible.

Aarseth himself has created a mask.

He 3D-printed one of the many faces from the Oseberg find and carved a large version out of wood.

References:

Brøgger et al. (ed) Osebergfundet, bind1-3 (The Oseberg find, volumes 1-3), The Norwegian State, 1917 -1928.

Christensen et al. Osebergdronningens grav (The Oseberg queen's grave), Schibsted, 1992.

Lindtveit, T. & Nyquist, F.P. På hjul i Norge. Fra Osebergvogne til vogn uten hest. (On wheels in Norway. From the Oseberg wagon to a horseless carriage), Grondahl, 1971

———

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no