Researchers found more pieces of the world's oldest runestone – may change the history of runes

The news spread worldwide when the nearly 2,000-year-old Hole runestone was discovered. New findings may change parts of our linguistic history, according to researchers.

During an excavation in 2021, a runestone was found in a grave in Ringerike, Eastern Norway.

The news spread globally because it turned out to be the world's oldest known runestone. It may be nearly 2,000 years old.

The stone had an inscription that researchers deciphered, but that turned out to be just the beginning of the story. Now, researchers have discovered much more.

Part of a larger puzzle

The stone is now called the Hole runestone (previously the Svingerud runestone), and new research delves into the secrets this stone has carried for many centuries. It was, in fact, just a fragment of a much larger stone.

"When we communicate research, we like to compare it to solving a puzzle. This time, we actually had to put together a puzzle," Kristel Zilmer tells sciencenorway.no.

She is a professor of runology at the University of Oslo's Museum of Cultural History.

Sciencenorway.no wrote about this stone in 2023 when it was first presented.

After examining this stone and other fragments from the grave, it became clear that the fragments they found were part of the same stone.

A new research article in the journal Antiquity reviews the archaeological findings and rune inscriptions.

What makes this find particularly remarkable is that researchers have been able to estimate when the runestone was created.

"Without such a well-documented context and reliable dating, many would likely have been sceptical of this stone," Zilmer believes.

This is because it differs significantly from previously known runestones with older runes. The early dating suggests that other runestones may need to be reconsidered in a new light, according to researchers.

The world's oldest known runestone

It is not possible to precisely date the stone itself, but the stone was found in a grave that provides a strong clue.

The Hole runestone was discovered in a burial site containing the remains of a funeral pyre – what is known as a cremation burial. This makes it possible to date the grave and the stone using radiocarbon dating. This method relies on dead organic material, such as charcoal or bones, to work.

The dating places the stone between 50 and 275 CE, making it the oldest known runestone in the world.

There are some other runic inscriptions on objects from around the same time, such as a Danish knife. But no known stones with such a clear dating framework.

But what do the inscriptions say, and why is the stone fragmented?

A larger stone that has shattered

The stone comes from a burial site that was hidden beneath a burial mound. However, the mound itself was unrelated to the graves beneath it, which were discovered by chance during excavations for the construction of the Ringerik Line railway.

It's remarkable if this was done by a female rune carver.

"We truly did not expect anything like this," Steinar Solheim tells sciencenorway.no.

He is an archaeologist and project leader for the Hole runestone research, and has been studying this discovery for several years.

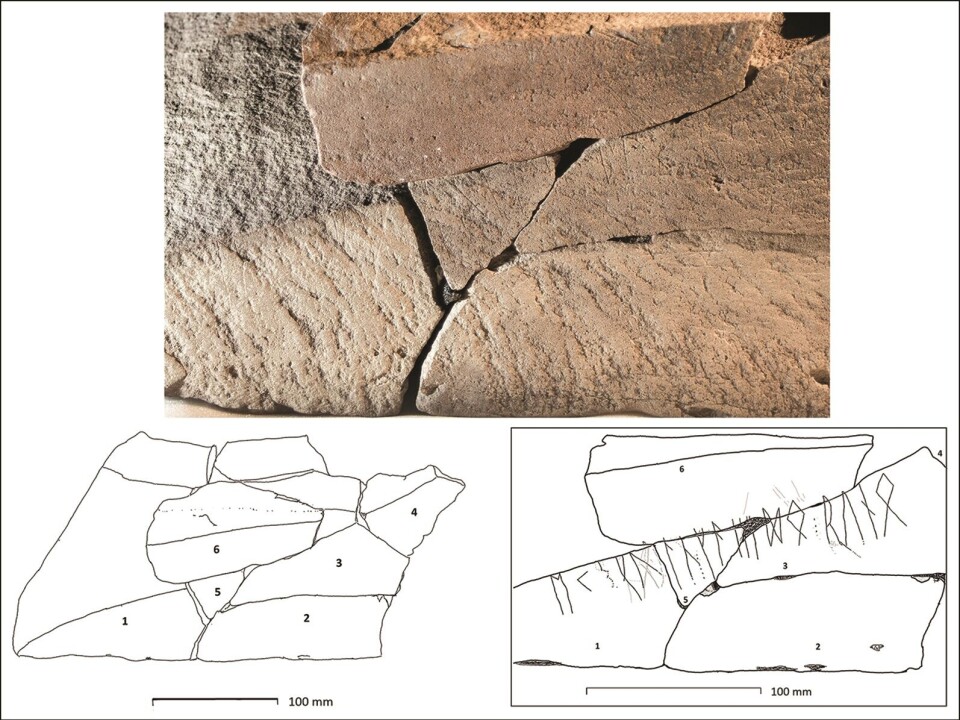

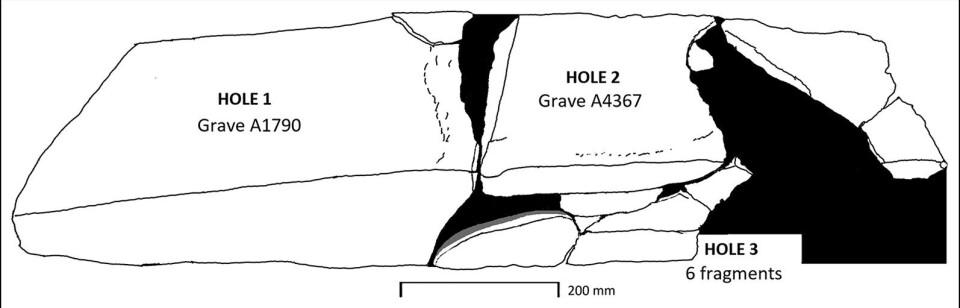

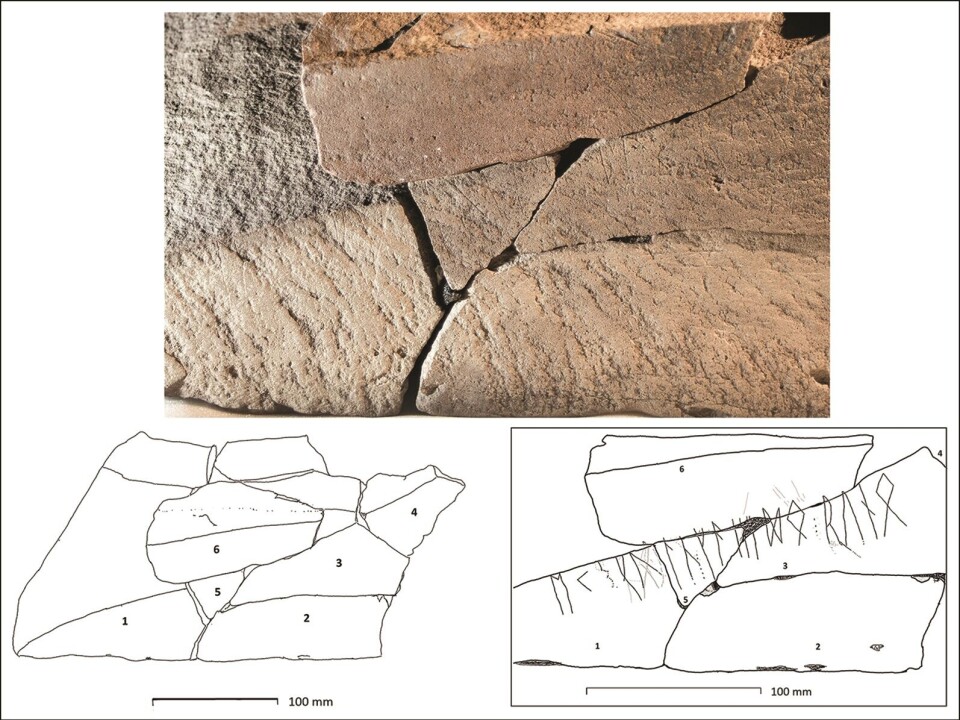

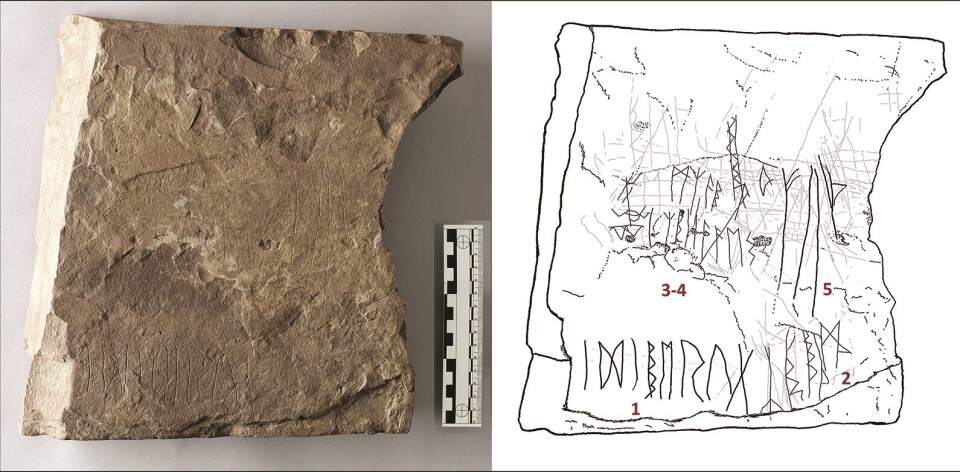

Over time, it became clear that archaeologists had multiple fragments of the same stone. They have now named these different pieces Hole 1, 2, and 3.

Together, the fragments form a larger stone. Solheim explains that it is likely they were once part of a large, upright stone, similar to a standing runestone or a monument.

"We don't know what happened; the stone may have been deliberately smashed," says Solheim.

There is a possibility that the deceased was buried with a piece of the runestone, perhaps inscribed with a name, as a possible memorial.

However, this remains an educated guess and cannot be confirmed, according to the researchers.

The largest fragment, known as called Hole 2, was placed in a grave. Other fragments may have been deposited in locations that also contained graves, but archaeologists have not found human remains in the other suspected burial sites.

It is also unclear whether the runic inscriptions were carved before or after the stone broke into pieces. However, some runes appear on a fracture surface, meaning the stone must have been broken before those particular runes were inscribed.

But the meaning of the runes on the fracture surface remains uncertain.

Names and futhark

Many of the runes and carvings on the stone are difficult to read and interpret, Kristel Zilmer tells sciencenorway.no. She has spent a long time deciphering the inscriptions on these stones.

Some inscriptions are relatively clear, though they still allow for multiple interpretations.

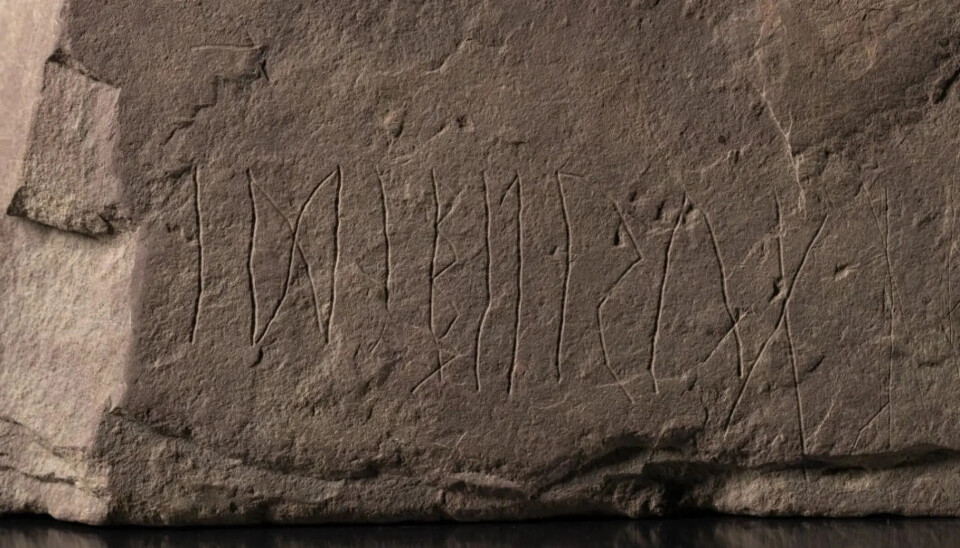

One of the inscriptions on the fragment with the most carvings appears to be a name: Idiberug.

This particular fragment was found in a confirmed burial site.

This piece contains numerous carvings and short runic inscriptions, including several symbols that may represent the earliest characters of the old runic alphabet, known as Futhark.

A female rune carver?

When researchers realised that multiple fragments fit together, they began searching for other matching pieces.

And they found more.

"We were missing a few pieces from the middle of one inscription, so we sifted through the soil. Then we found two pieces that fit perfectly into the inscription," says Zilmer.

These newly connected fragments revealed another inscription, faint but still legible. This combined section is called Hole 3.

There are still small damages and wear that make certain characters difficult to read, leaving room for different interpretations, Zilmer explains.

The inscription begins with 'I', followed by a name that is difficult to decipher. Possible interpretations include Gul(l)u/Wu(l)u or Swul(l)u/Skul(l)u, along with a verb meaning to write, and finally the word for rune, which directly refers to the inscription itself, according to Zilmer.

Since the name ends in -u, it could indicate that it is an Old Norse female name. Combined with the verb, it appears to be a kind of signature from the one who carved the runes, Zilmer explains.

"It's remarkable if this was done by a female rune carver, as there are very few traces of them elsewhere," says Zilmer.

What does the rest mean?

There are many other carvings, especially on the Hole 2 fragment. Some may be runes, while others could be ornamental.

"Interpreting everything on the stone is both challenging and complex," says Zilmer.

She emphasises that their study lays a foundation for understanding the runes in their new article. She and Krister Vasshus have also written another article that delves deeper into runology in the journal NOWELE.

"In some places, there's a fluid transition between writing and imagery. We may never find definitive answers, but this discovery will spark discussions for years to come," she says.

A tradition

Sciencenorway.no also discussed the new findings with Michael Schulte, a professor of Nordic linguistics at the University of Agder, a runologist, and an expert in early Nordic language history.

Although he did not participate in the new research, Michael Schulte, an expert familiar with the Hole runestone inscriptions, acknowledges the study as a solid piece of research.

He has not participated in the new research, but he points out that this appears to be solid research. Schulte is well acquainted with the inscriptions on the Holesteinen.

"It's a solid and well-founded article," he tells sciencenorway.no.

"However, what I would add is that this is clearly a form of experimentation with writing in an early phase of literacy," Schulte believes.

He argues that the Hole 2 fragment (which contains the most writing) shows signs of several different types of writing usage side by side.

Schulte explains that some runes are lightly etched, while others approach a more 'monumental' style, resembling inscriptions found on large stones from the classical period.

He argues that this stone originates from a phase of extensive experimentation with written language.

"The carver was exploring the potential of writing and trying to master the script," says Schulte.

Could change the history of runes

Schulte points out that the shape of several runes on the Hole runestone differs from later examples.

Schulte also highlights that this stone alters some of the timeline of runic history, as it comes with an archaeologically confirmed dating.

"We've established our grammar and linguistic history. But this stone changes our understanding of what the oldest runes actually looked like," he says.

Runic forms have also been used to date runestones, though often on uncertain grounds.

Schulte points out that the dating of older, well-known runestones, such as the Hogganvik runestone and the Tune stone, may need to be revised in light of this discovery.

"We may have to redate some inscriptions that were previously dated based on such criteria – all because of the rune inscriptions from Hole," he says.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

References:

Solheim et al. Inscribed sandstone fragments of Hole, Norway: radiocarbon dates provide insight into rune-stone traditions, Antiquity, 2025. DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2024.225

Zilmer, K. & Vasshus, K.S.K. 'Runic fragments from the Svingerud grave field in Norway. Earliest datable evidence of runic writing on stone', NOWELE North-Western European Language Evolution, vol. 76, 2023. DOI: 10.1075/nowele.00080.zil (Abstract)

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.