This ship part found in Norway is much older than archaeologists first thought

The wood dates back to the late 11th century, close to the Viking Age.

Archaeologists from the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU) have investigated yet another area in Bjørvika in Oslo, a few hundred metres from the Opera House and Barcode.

A recent discovery turned out to be quite different from expectations.

The seabed in Bjørvika is strewn with shipwrecks

The seabed in Bjørvika is strewn with the wrecks of abandoned and burned ships.

There are most wrecks from the 16th and 17th centuries, the Renaissance.

“Some wrecks are newer. There’s a handful from the 15th century. The 14th century is quite well represented after our excavation. We’ve only found one wreck from the 13th century,” NIKU archaeologist Håvard Hegdal tells sciencenorway.no.

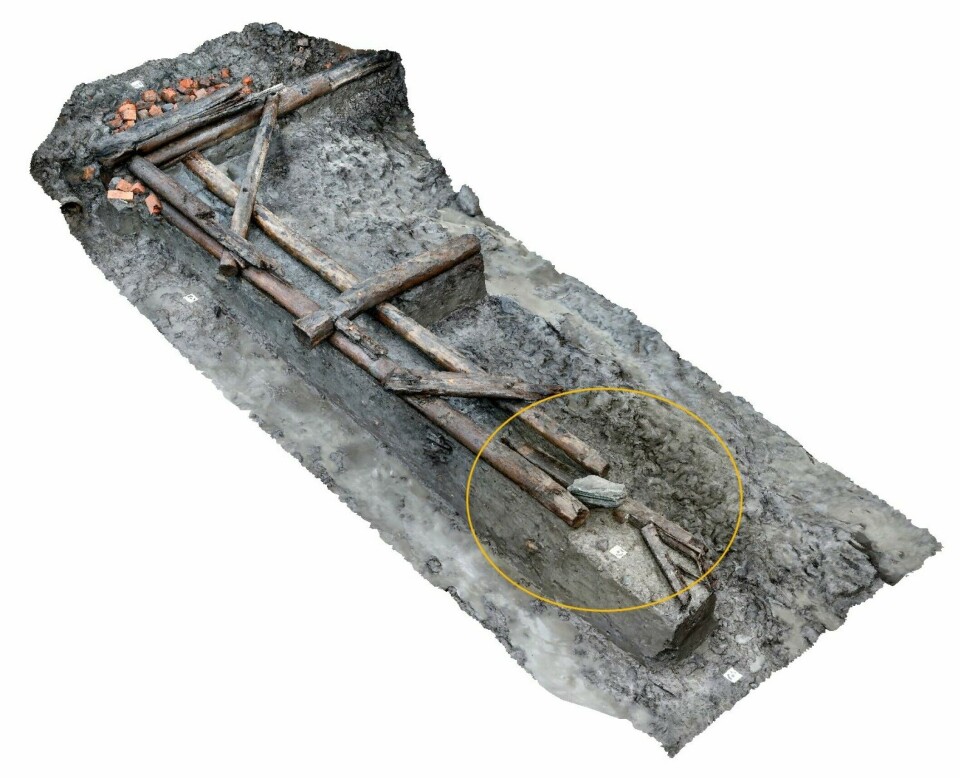

Then the archaeologists examined a surprisingly well-crafted ship part, retrieved from the well-preserved conditions in the clay in the innermost part of the Oslofjord.

Fantastically well-formed

“This piece of wood was fantastically well-formed,” he says.

Hegdal says the ship part was found under a wharf that the archaeologists have dated to around the year 1300. Therefore, it was natural to assume the ship part could be about as old.

“At the same time, we saw that the shape of this part differed significantly from the other findings in the same area,” he says.

Dated to the late 11th century

The archaeologists decided to cut off a piece of the wood and send it for dating.

“We were really surprised when the dating came back on June 27. It revealed that the tree sprouted in the year 1035. It was felled sometime between 1087 and 1100,” he says.

The part is thus 200 years older than the wharf above it. And that’s a big mystery, Hegdal thinks.

“Because if the dating is accurate, then we’re right at the end of the Viking Age,” he says.

Founded by Harald Hardrada

The Viking Age is commonly considered to have ended when Harald Hardrada lost the battle at Stamford Bridge in England in 1066. Harald is believed to have founded the city of Oslo just a few years earlier – in 1048.

At the end of the 11th century, when the ship might have sunk, Oslo was still a relatively small town. But it had begun to develop into an important trading centre in Norway.

Harald Hardrada was Norway's last Viking king. His wife was Princess Elisiv from Ukraine.

There was likely settlement in Oslo also earlier in the Viking Age, before Harald Hardrada is officially credited with founding the city.

Special aesthetics

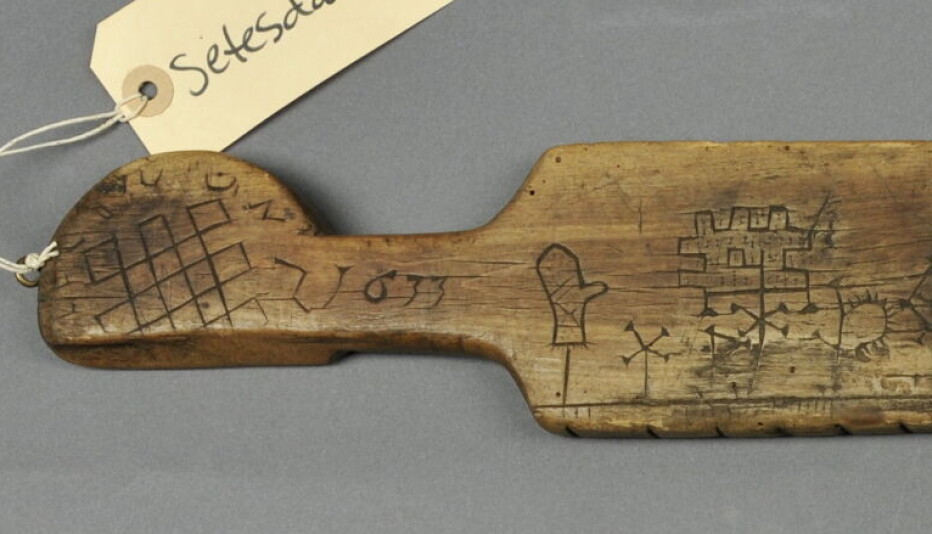

“There’s an aesthetic quality to the ship part we’ve found that we don’t find in the more roughly hewn parts from cargo ships and work ships made in the Middle Ages,” Hegdal tells sciencenorway.no.

“In older ships, it sometimes happens that the planks in the hull are decorated externally with planed lines. But this ship part has decoration on all sides. Even where it has barely been visible,” he says.

Hegdal emphasises that the ship part from Bjørvika cannot be compared with Viking ships like the Gokstad ship from around the year 890, which features more complex lines and specialised planing.

“It showcases both advanced maritime technology and exquisite aesthetics,” he says.

The wood has ‘fingerprints’

Dendrochronology is the best technique for dating a piece of wood like this. C14 dating offers very low precision for the early medieval period, which the archaeologists are dealing with here.

“Oak trees that grew in Norway during the Middle Ages are well-studied. So here, the rings work well as ‘fingerprints’ when we try to date old wood,” says Hegdal.

Exceptional preservation conditions

Up until 400 years ago, the Oslo harbour was located in Bjørvika.

The clay here at the innermost part of the Oslofjord has provided extremely good conditions for preserving old wood. Timber from the early Middle Ages is so well-preserved that it looks as if it was felled yesterday, the archaeologists report.

They often find other organic materials as well, such as bones, leather, and rope.

Large parts of Bjørvika have never been thoroughly investigated by archaeologists before the project started in connection with major developments in the area.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no