What did the Vikings really eat?

Norwegian researchers are working to find out more about what the Vikings cooked in their cauldrons.

Stews, soup, fried pork, porridge and bread are some of the things that Vikings ate. The warriors were fond of barbecued meat. Abundant food and beer were expected at parties.

Researchers are now working to find out more about this ancient food culture.

More about meat and porridge later. But first: greens.

Anneleen Kool is a botanist and researcher at Oslo’s Natural History Museum.

She believes the Vikings used more plants in their food than we have been aware of until now.

“In the scientific tradition, it’s been more common to study the relationship between animals and humans than the relationship with plants,” Kool says.

Kool and her colleagues are now undertaking a major project. Their goal is to learn how plants were used over a thousand years ago. Few written sources from the Viking Age exist, but information may lie hidden in ancient traditions, archaeological finds, or place names. The sources extend from the Viking Age to the present day.

“We’re looking at whether plants can be traced back to certain places. We’re applying the knowledge we gain to the same kind of models that are used to look at the evolution of animals and plants. But instead of using DNA, we’re using our knowledge about plants, with language as a tool,” says the botanist.

The Viking vegetable

The Viking garden is part of the University Botanical Garden in Oslo’s Tøyen neighbourhood. It contains plants that scientists believe were used during the period.

You won’t find potatoes, cucumbers, carrots or tomatoes here. All these foods came much later.

Kool points out one of the plants that researchers have already learned a lot about: Norwegian angelica (Angelica archangelica), also known as wild celery. The researchers have run a test analysis of this plant using the model.

Angelica is a vigorous plant that may be easy to dismiss as an unattractive mountain plant. But all indications show that it was an important vegetable in the Viking Age.

Both the leaves and the stalk were used, and perhaps also the roots.

The taste is somewhat special. The stalk is reminiscent of soap and celery. Kool notes that the flavour is better before the plant blooms.

The Frostathing Law, one of Norway’s oldest laws, was compiled and written down between 1000 and 1200 CE. The law states, "If one man goes in another man's onion garden or angelica garden, then he is lawless." This indicates that it was common to grow angelica and onions on farms.

Angelica also appears in the sagas. Olav Tryggvason's story relates that he brought a stalk of angelica to his queen, Tyra. But she wasn’t charmed. She thought it was a pitiful gift, and besides, there was no angelica in Denmark where she came from. She asked him instead to go pick up her dowry, and that turned into Olav's demise.

Peas and onion soup

Archaeological finds have been made of ancient pea types with geographical designations of origin, such as jærerter (from Jæren in southwest Norway) and ringerikeserter (from Ringerike district), and gråerter (grey pea, Pisum sativum var. arvense). Peas were probably cultivated already in the Viking era,” says Kool.

The Vikings also had access to various allium species. Several rune inscriptions include the words "beer, flax and onions."

"In some coastal areas you can find sand leek (Allium scorodoprasum) in huge quantities," says Kool.

“One hypothesis is that wild onions were used in the Viking Age and that is why they have become so common. The same goes for the victory onion, which grows in Lofoten all around an old Viking settlement. There are really large amounts of it there,” she says.

People probably ate the leaves and not the bulb. The leaves on the giant garlic have a strong taste of onions and garlic. Research from Sweden suggests that it was also common to share and exchange yellow onions, perhaps even in the Viking era, says Kool. The research is presented in an article from Linköping University.

Garlic seeds from the Viking period have been found in York, England, and may well have also been cultivated in Norway.

Onions were actually used for diagnosing illness.

“They made onion soup and fed it to individuals who had been stabbed in the stomach with a sword,” says Kool.

If the wound smelled oniony, that was a sign that the person couldn’t be saved.

“The smell meant there was a hole in the intestines. It was the end of the run and a way of sorting the injured,” she says.

Kool and her team have not yet analysed the uses of the wild onion varieties yet.

“But I'm guessing that onions were probably used as a food plant, in addition to being a medicinal and diagnostic plant.

Weeds or useful plants?

The Vikings loved common yarrow.

“Yarrow has long been used in beer brewing. A lot of dialect names refer to it being used like hops,” says Kool.

Pollen analyses show that yarrow was introduced in Greenland in the Viking Age.

“Yarrow came with the Norwegians. There was quite a lot of it there while they lived there, and less afterwards,” the researcher says.

The study was published in the Journal of Biogeography in 2013.

"Doing statistical analyses on this kind of data is a good idea, because it’s so easy to think that a plant was just a weed, since that’s how we think of it now," says Kool.

The same goes for other plants, she says, like pigweed (or lamb’s quarters, Chenopodium album), which is a common weed and a relative of spinach. It grows eagerly in the bed of cereals in the Viking garden.

“Pigweed seeds appear in a lot of archaeological excavations. Some people still use the plant in soups occasionally,” says Kool.

It may well be that pigweed was also used in soups in the Viking era, which the analyses could reveal.

Kool believes that gleaned plants were part of the Viking diet.

“You find a lot of different types of plants around Viking settlements,” she says.

Cereals, beef and milk

What else did people in the Viking Age subsist on?

Jon Vidar Sigurdsson is a professor of history at the University of Oslo and an expert on the Viking and Middle Ages.

Cereals were very important, he says.

“Grain was everyday food for most people. But research suggests that warriors ate more meat.”

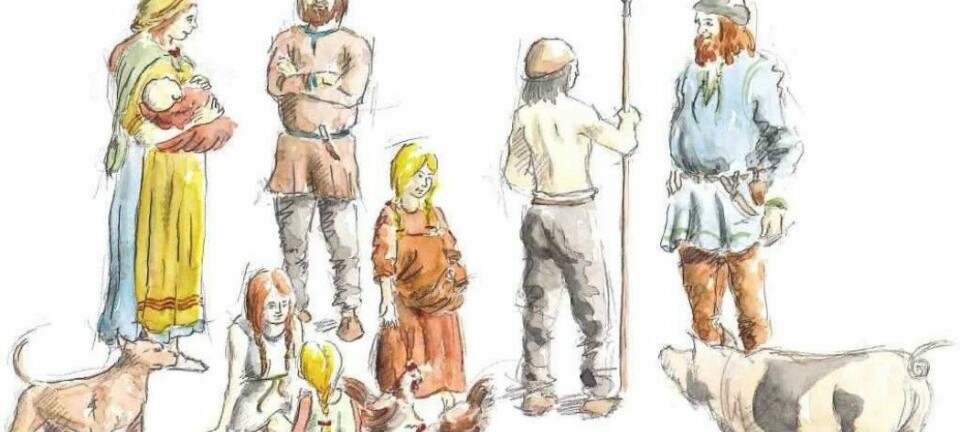

The Vikings kept cows that provided milk and meat. These were important elements in their diet, along with the butter, buttermilk and cheese they made. Some people also kept pigs and chickens. Sheep were important for the wool to make clothes and sails, and mutton was also eaten.

Sigurdsson emphasizes that there were regional differences.

“In the north people probably ate more fish. Growing cereals on a large scale is difficult in the north. Probably a lot of the grain was used for beer there, because making a lot of alcoholic beverages was important,” he says.

Then you have to remember too that the social differences were huge, says Sigurdsson. Those differences were clearly reflected in the diet and what people had the possibility of eating. The chieftains’ farms had the best food.

“Surveys done in Lofoten indicate that farmers and slaves had pretty similar diets. There was a lot of fish and marine protein, whereas the chieftains generally ate more meat.”

The hunt

“People hunted everything,” says Sigurdsson. They used bows and arrows a lot, as well as animal traps.”

“Up north they ate a lot of reindeer. The animals would be captured and driven into a large fenced enclosure. It was a mass slaughter of reindeer.”

Hunting was also important to obtain raw materials such as fur, hides, sinew and antlers.

Kim Hjardar is a historian and associate professor with a major in the Viking era. In a Norwegian article in the journal SIDE3, he describes how people hunted.

It was common to use traps to catch small game, he said. Birds were widely hunted by the elite. The Vikings also tamed falcons for bird hunting.

Hunting for the largest animals, such as moose, bear and the now extinct aurochs was reserved for the elite, according to the historian. The Vikings hunted mostly in hunting parties organized by people of high status. There were rules for who held rights to hunt in the different areas.

People also collected berries, mushrooms and nuts in the forest, says Sigurdsson.

“This was a society that lived from hand to mouth. Everything you could eat was taken advantage of, and you obviously didn't throw away food,” he says.

Made stews with red wine

Grethe Bjørkan Bukkemoen is a PhD candidate in the Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History at the University of Oslo. She is writing her doctoral dissertation on meals and food preparation in the Iron Age.

She talked with sciencenorway.no on a Zoom call and was joined by Marianne Vedeler, a professor at the Museum of Cultural History. Vedeler is currently involved in a project on food culture in the Middle Ages. She has also done extensive research on the Viking Age.

In the project, Vedeler and colleagues have investigated burnt remains in old soapstone pots from medieval Oslo. They made an exciting discovery.

The researchers found remnants of quite advanced cooking in the pots. Even the ordinary shoemaker made dishes with red wine, root vegetables and fish.

“Little of this kind of analysis has been done on Viking Age cooking pots,” says Bukkemoen. “It's an area I really want to work on when I finish my dissertation.”

There are also other ways of investigating the food culture.

Cooked meat and vegetables in big cauldrons

Kitchen technology underwent a big change in the period before the Viking era. This period is called the Merovingian Age and lasted from 550 to 800 CE. Some people started using cauldrons made of iron that were hung over the fire, making it possible to prepare food in a new way.

“This method wasn’t common before then. The older way was to use ceramic vessels that were probably placed into open hearths. Cooking pits were also frequently used to prepare food,” says Bukkemoen.

The Viking age saw the advent of soapstone pots. Soapstone was found virtually everywhere in Norway, and it was easier to make pots from soapstone than from iron. Pots became more accessible to most people.

Forks to spear food from communal dishes came into use in the Merovingian Age and are also found from the Viking Age.

“Forks were probably used to take things out of the pot. This would indicate that there must have been some chunky ingredients in the stew pot, which I imagine would have been meat or different vegetables,” says Bukkemoen.

“What we can see from analyses of food remnants in the pots so far is that they probably put a lot of different things in there and cooked them,” she says.

The Viking Age studies show a mixture of several ingredients, such as meat, vegetables and dairy products.

Vedeler says that the way food was served was different from how it’s done today.

“We’re very used to having a place setting for each person. But that’s a much more recent phenomenon. It's a completely different way to eat than when people gather around a large communal vessel. People might have picked up whole pieces of meat and eaten with their hands or used a chunk of bread.

They didn’t have forks, but knives were used.

Danish researchers have described the Viking way of serving food as a kind of tapas, as described in this Norwegian Dagbladet article.

Access to herbs and vegetables

So what do we imagine the Vikings cooked in their pots and bowls?

Honey, nuts and berries were available to them.

In addition to the angelica, onions and peas, the Vikings had access to herbs and other plants.

Seeds of coriander, thyme, mint and dill from the period have been found. Parsnip grew wild. So did bulbous oat grass (Arrhenatherum elatius subsp. bulbosum). It has a tuber reminiscent of a potato, says Kool. The root has been found in graves.

She points out a patch of the oat grass in the Botanical Gardens. It looks like straw, but the root is compact. She hasn't tasted it yet. She’s thinking of trying a bit of it this year.

Cabbage was domesticated during this period and was one of the first vegetables that people in Norway used. Kool believes it’s likely that it was grown as early as the Viking Age.

Earlier it was believed that ground elder (Aegopodium podagraria) was introduced in the Middle Ages. But it was found in Scandinavia before that, she says.

“Ground elder has probably been used as a vegetable for quite some time,” says Kool.

The Vikings might also have used nettle. A bag of nettle seeds was placed in the Oseberg burial site, along with a bucket of wild apples, plums and blueberries.

Other plants they might have used in food, but of which no archaeological findings exist yet, are sea buckthorn, caraway and baldmoney (Meum athamanticum). The list is far from exhausted.

“People were probably experimenting with what they could grow, just like we do in our kitchen gardens now,” says Kool.

“A peach stone was among the discoveries in northern Germany and southern Denmark. It appears to have been broken open. Presumably some Viking tried to cultivate it when they brought peaches back from a trip, thinking it would be nice to have some at home.

Bread not as we know it today

In the Merovingian Age, the period before the Viking era, the frying pan made its debut, and with it a new way of making bread, say Bukkemoen and Vedeler.

“You could make thinner kinds of bread, a little more like Norwegian lefse – or tortillas or chapati,” says Bukkemoen.

The bread wasn’t leavened with yeast like today, says Vedeler.

“Yeasted bread first showed up well into the Middle Ages,” she says.

In Sweden, older types of bread have been discovered that look like small rolls, says Bukkemoen. They were probably baked in the hearth coals or in small ovens.

“The rolls must have been quite hard, and were probably best eaten fresh,” she says.

The breads were mainly made from barley flour and oats. Rye and wheat became somewhat more common in Viking times.

“With the advent of the frying pan, making thinner, flatter bread loaves became more popular. Some people also used cooking grills that were placed over the hearth. Pan frying thin bread was another way to show status and distinguish oneself. Since yeast was not used, it was difficult to have the bread bake through if it became too thick,” says Bukkemoen.

Forced to eat porridge until he burst

Porridge is a common staple in world food history, and the Vikings made it, too.

“We can see that the rotary quern, which is a type of hand grinder for making flour, very clearly came into use as a tool in the Viking era,” says Bukkemoen.

“Flour is used in bread, of course. But it is also very nice to be able to use it in porridge. Various types of porridge and pap were probably an important part of daily living.”

Pap is a thin soupy porridge. It was made from different cereal types, and plants may also have been mixed into it.

The Tale of Sarcastic Halli (Sneglu-Halli in Icelandic) is an Icelandic short tale about a skaldic poet who lived in the mid-1000s. He was outspoken and brazen and sometimes also called Grautar-Halli, or Porridge Halli. He loved porridge, especially with butter. For a time, Sarcastic Halli was in the service of King Harald Hardråde. The king thought he was greedy.

At the table, King Harald helped himself first, and when he was satisfied he pounded the table for the servants to come and clear away the food. The rest of the party was usually not yet finished eating. Sarcastic Halli complained and claimed that Harald was starving him. The king was not pleased at Sarcastic Halli’s boldness.

Later, King Harald arranged for Halli to be served a huge trough of porridge. When Halli couldn't eat anymore, King Harald drew his sword and said he should eat until he burst.

"Kill me, King. But not with porridge!” the skald apparently responded. King Harald relented and returned his sword to its sheath.

According to the tale, when Sarcastic Halli finally died, it was in front of a bowl porridge.

"The poor man must have burst from the porridge," Harald is said to have quipped when he received word of Halli’s death.

How important was porridge really?

Vedeler notes that there was a lot of talk about porridge and how important it was.

“But it would be incredibly fun to take a closer look, because we don't really know that much about it. I must say that I’ve been surprised now that I’ve studied medieval soapstone pots dating back to the 1100s. I expected – and so did most of the other researchers – to find a lot of porridge remnants in those pots, and that wasn’t the case at all,” she says.

“We might ask how important porridge actually was for the Viking Age diet,” says Vedeler.

Bukkemoen agrees that this would be exciting to look into, “because you read sources from recent times, and assume porridge was very important in the Viking era as well. I've been a bit involved in looking for this porridge, but I haven’t seen much sign of it either.”

They both agree that people of the Viking era certainly made porridge. The question is how much and how often.

Bukkemoen points out that much of the research on food in the Viking Age is based on sources that were written down much later or on known food traditions of more recent times.

“It’s important to nuance this image by looking at what can be found in the archaeological material,” she says.

Heaps of beef

Beef – of all the types of meat available – was clearly the most important meat in the Viking diet.

“Beef is what we find a lot of remains of when it comes to animal bones. Not only in Norway, but also other places in Scandinavia,” says Bukkemoen.

Cattle bones are located in large waste piles around the Viking settlements. The researchers also see plenty of traces of sheep, goats and pigs.

Fish was important, and we’ve found some indications that the trade in stockfish from the north began as early as the Viking era, says Vedeler.

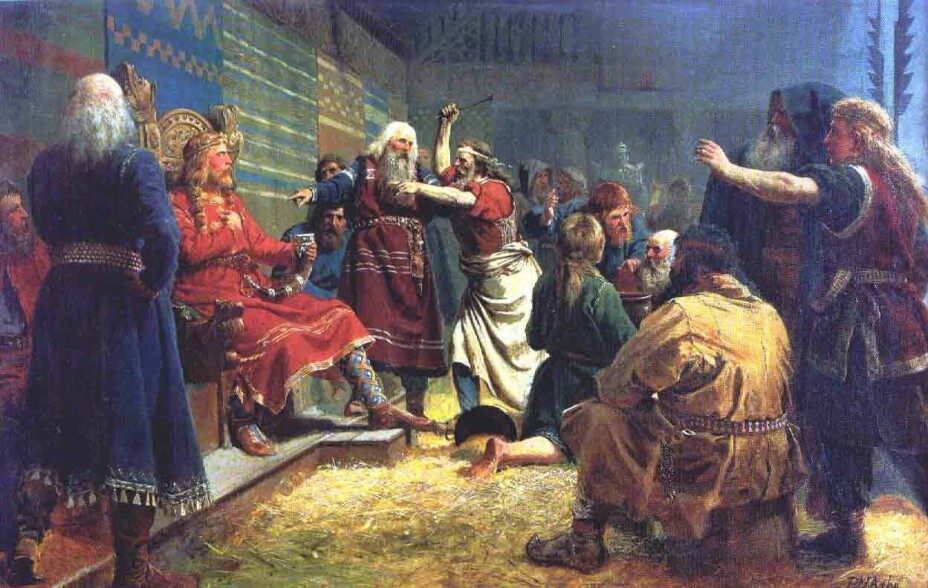

An abundance of meat and beer was expected on feast days and at sacrificial festivals. The celebrating often lasted for several days.

“The social system was structured such that the well-to-do needed to build loyalty with people to maintain their support, for example politically. So it was important to arrange large gatherings where you could show off how wealthy you were,” says Bukkemoen.

According to medieval sources, horse meat – in addition to other meats – was eaten at sacrificial festivals, according to Vedeler. Eating horse meat was probably related to religious tradition and was later strictly forbidden.

“We don’t know whether horse meat was only eaten in religious contexts or otherwise,” Vedeler says.

"The topic of horse meat is interesting," says Bukkemoen, “because we don’t find many remains in the settlements. But we see that horse bones were sacrificed or deposited in wetlands. That would support what Marianne says about appearing to be associated with special meals in a religious or ritual context.”

At big festivals, the animals were probably slaughtered in advance. In some places, cattle skulls have been found that were placed on stakes around large halls. This indicates that slaughter was also associated with special rituals and gatherings,” says Bukkemoen.

Warriors enjoyed grilling

Written sources tell us that warriors were fond of grilled meat, says Sigurdsson.

This is supported by archaeological finds.

Roasting spits and forks have been found, which were probably used by the social elite, says Bukkemoen.

These utensils enabled them to grill finer cuts of meat and birds over an open flame.

The Bayeux Tapestry, which shows the Norman duke William the Conqueror's invasion of England in 1066, includes a scene where birds and fine cuts of meat are being roasted on a spit.

Some of the spits that have been discovered are long enough to roast a suckling pig on, says Bukkemoen. The spit would be placed across vertical supports over the fire and turned.

How varied was the diet?

The Vikings had access to many different raw materials, both on the farms and what they gleaned from nature.

As to how varied their diet was, “we still have some work to do on that question. But there are a lot of exciting sources that we can tap into,” says Vedeler.

Bukkemoen agrees. “We know a lot about what was available. How it was used is harder to say.”

We’ll have to use our imagination for the time being.

Bukkemoen says that an important point is that food traditions weren’t static over time in the Viking era, either.

“We have to realize that what the Vikings ate and how they prepared food changed over time. They travelled extensively and were probably also influenced by outside impulses – just like we are,” she says.

Kool, who is working on the plant project, says that while other cultures were writing about their medicinal and food traditions, the Vikings didn’t write anything down.

“Knowledge that is only passed on from person to person has a greater chance of disappearing,” she says.

She hopes that the research now being done can dig up more knowledge about old forgotten food traditions.

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse

———