Study finds that sharks may have been part of Stone Age Norwegian coastal diets

Porbeagle sharks supposedly taste like veal, and were a formidable opponent. Catching one may have conferred high status, according to a researcher.

The porbeagle shark is one of the most common sharks off the Norwegian coast, and it has been swimming in these seas for a very long time.

“The porbeagle shark is the great white shark's cousin. It’s a pretty brutal fish,” Leif Inge Åstveit says. He is an archaeologist and researcher at the University Museum of Bergen.

Åstveit has worked on several different excavations in Western Norway, and on one occasion they made a rare discovery: lots of porbeagle teeth.

“It was hugely exciting to make that kind of discovery,” Åstveit says.

Several thousand years ago, someone here might have fished, eaten, and then used shark teeth for some purpose.

And even though people and porbeagle sharks have both lived along the coast in Western Norway for many thousands of years, this is an unusual find.

The people who lived here in the Stone Age probably survived mainly on birds, fish, shellfish, and crabs, Åstveit tells sciencenorway.no.

Food was easy to obtain, and people’s living quarters were very close to the food source. But at some point around 4,500 years ago, people here may have started hunting something far more exotic.

One of the sites that the archaeologists have examined is on Nerlandsøya in Northwest Norway. More than 150 shark teeth have been found here in various layers in the ground.

Åstveit believes this indicates that people in this area have been fishing for porbeagle sharks for a long time – perhaps even as long as the settlement was in use. He describes the findings in a new research article in the Norwegian archaeological journal Viking.

And more porbeagle shark teeth appeared at three other sites when Åstveit looked through collected teeth and bones. They yielded only a small handful of teeth that date from roughly the same time period.

The old settlement on Nerlandsøya was thus in a class of its own, with the discovery of over 150 teeth spread over a long period of time.

People have lived here for a long time. The settlement on Nerlandsøya was in use for several hundred years between 2800 and 2200 BCE, and researchers have found remains of dwellings, hearths, bones, and tools made of flint and slate.

And also shark teeth.

Tastes like veal

The size of the teeth suggests that the sharks were between 1.5 and 2 metres long. The teeth are also the only part of the body that was preserved, since most of the shark's skeleton is made of cartilage and thus decomposes.

Norway has poor preservation conditions with very acidic soil in much of the country, so skeletal remains often break down.

“It could be that shark fishing was more common than we think, but that the skeletons have disintegrated,” Åstveit says.

But what kind of shark is a porbeagle? It is large, and the largest can weigh over 200 kilograms and be over 3 meters long. The porbeagle resembles its close relative, the great white shark.

Researcher Keno Ferter from the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research (IMR) describes it as the strongest fish he has encountered, and that trying to catch a porbeagle is both exciting and terrifying, which you can read more about at sciencenorway.no. Ferter and the other researchers caught the shark so that they could tag it.

The porbeagle is said to have good flavour. IMR describes it as a delicacy with meat that is similar to veal. Fishing for porbeagles reached a peak in the 1930s, when 4,000 tonnes were caught.

The fishing led to a sharp decline in porbeagle numbers. This species is now totally protected both in Norway and the EU.

Most viewed

No content

But Stone Age people probably had several good reasons for trying to catch this shark.

Meat, oil and teeth

“The shark provided people with meat, oil, and teeth,” Åstveit explains.

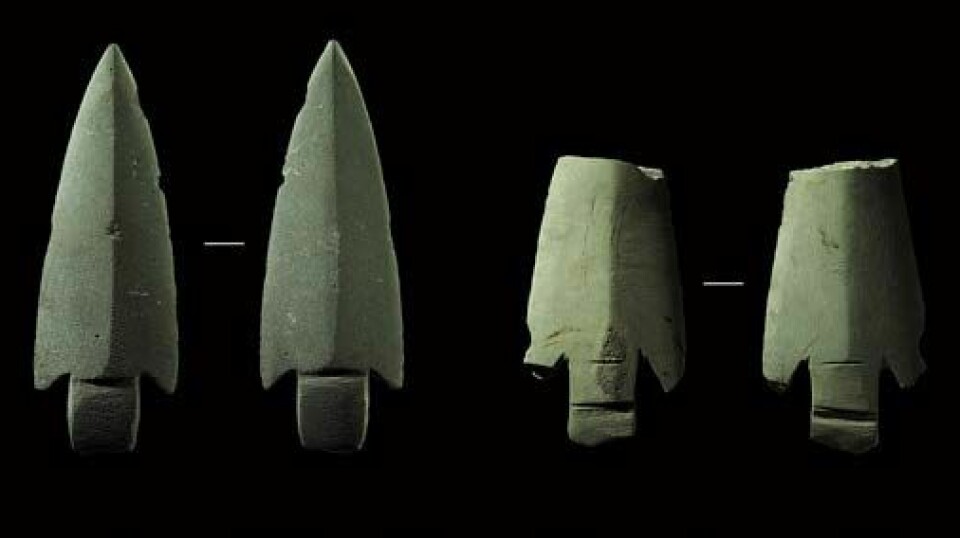

The teeth are sharp and might have been used as tools. The shark also has thick, strong skin that could have been used to make clothing. Another reason for fishing them might have been status.

Åstveit compares the shark to large game on land and writes in his study that shark teeth might have been used as tools or ornaments that gave people high status.

He describes a change in Stone Age society that began around 4,500 years ago. The networks between people grew larger and more far-ranging, and other possible status objects appeared in settlements in Norway.

Gift network

When archaeologists examined Nerlandsøya, they found small amber buttons – square and polished pieces of amber that had come all the way from present-day Baltic to the coast of Møre and Romsdal.

Åstveit describes it as a ‘gift network’ that connected people across long distances.

“The objects show that they had extensive contact networks,” he says.

And it's not impossible that myths and stories were tied around the dangers involved in actually acquiring shark teeth, Åstveit says.

Obtaining shark teeth required people to go on longer and more demanding expeditions at sea, to both hunt animals and acquire high-status items.

Exactly how the sharks were fished or whether dead sharks were found on the beaches has not been answered by the findings. But if they were fished, special techniques would have had to be used to handle such a powerful animal.

Åstveit describes a technique known from the coast of Peru which involves luring the shark to the surface by using bait to splash like prey on the water’s surface. The shark could then be clubbed or beaten to death.

The hunters might also have used large slate-tipped spears to harpoon or thrust into the shark, such as have been found on Nerlandsøya.

Marine version of big game hunting on land

“This is a hugely exciting discovery,” Steinar Solheim says. He is an associate professor in archaeology at the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo and has worked extensively with coastal settlements in Stone Age Norway.

He was not involved in the new research, but he has looked at the research paper.

Solheim agrees with the interpretation that these shark teeth might be traces of so-called prestige hunting – hunting for both useful things like meat and leather, but also for trophies.

“We’re familiar with this from big game hunting on land,” he says.

Solheim points out that some similar finds have been made further south in Norway from roughly the same time period. In Agder county, another kind of big game hunting was conducted, but on bluefin tuna.

“Similar trapping techniques might have been used,” Solheim says.

Remains of bluefin tuna have been found at Jortveit in Agder, according to this Norwegian article in Norark.

Solheim is not aware of any directly comparable finds of shark teeth at other locations in Norway, but he does not rule out that sharks might have been caught elsewhere.

The problem is that conservation conditions vary greatly. In some places, a lot of information has been preserved, while other places are almost completely devoid of such information, says Solheim.

———

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Reference:

Åstveit, L.I. 'Hai på menyen. Håbrannfangst og sosialt liv i yngre steinalder på Nord-Vestlandet Shark on the menu' (Catching porbeagle sharks and social life in the Neolithic in Northwest Norway), Viking, 2023. DOI: 10.5617/viking.10589 (Abstract)