Frosty time machine coughs up arrowheads

When Stone Age hunters missed their targets they inadvertently turned snow patches into treasure chests.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Let's turn the clock back 5,400 years and meet a tribe of people preparing for the summer’s hunt in the mountains around Oppdal.

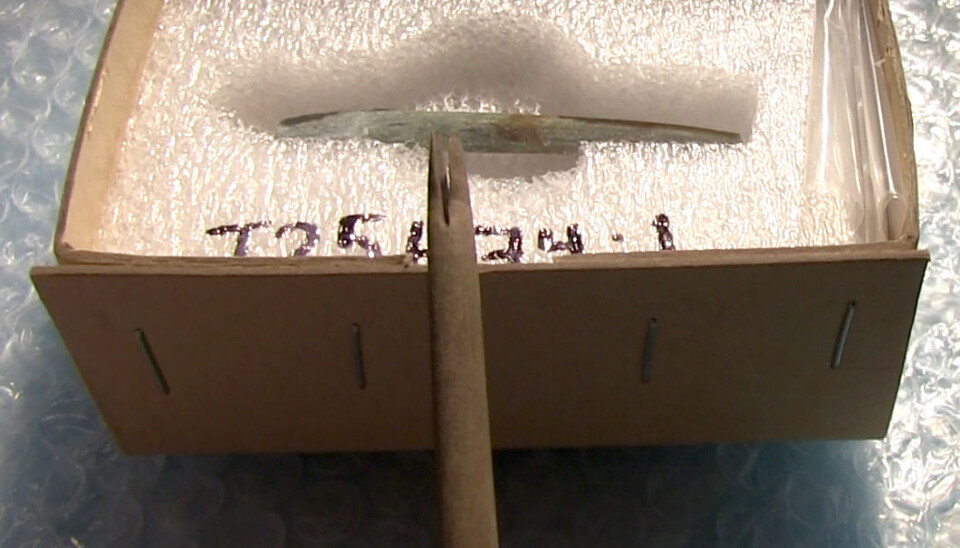

A shaft is cleaved from a pine and carefully carved until it is long, narrow and straight.

It will form an arrow that hunters hope will connect with a good supply of protein.

There is no flint in these parts, but slate can be readily chipped and ground into sharp, deadly points.

The arrowhead is attached with pitch made from birch bark and tightly wrapped with animal sinew.

Now the hunter is ready to find out whether dinner will consist of grouse or reindeer.

A vital miss

The bow is nocked and released. The arrow zings through the air. But this was an especially unfortunate shot. Not only did it miss the prey, the arrow drove deep into a snow patch. For some reason it wasn’t retrieved.

But it didn’t disappear for good.

“We archaeologists are reliant on hunters missing like that,” says Martin Callanan, from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), where he teaches in the Department of Archaeology and Religious Studies.

“When arrows disappeared deep into snow they sometimes froze there for keeps, until we find them,” he says.

One of his favourite artefacts is the arrow that disappointed a hunter 5,400 years ago.

Most come from the public

Callanan and other NTNU researchers are working with an international project called Snow Patch Archaeology Research Cooperation (SPARC), which has as one of its goals the finding and analysing of hunting weapons in perennial mountain snow patches around the country.

They get a lot of help from hikers and amateur scavengers.

“Amateurs who search as a hobby have found nearly everything we have,” says the researcher.

His favourite arrow was found by a mountain park ranger at Oppdalsfjellet in September 2011.

Callanan reasons that there are more snow patch treasures waiting to be found.

“A lot of finds have been made in the mountains of south Norway and some up in the high north. We expect there are loads of exciting artefacts waiting for us.”

The old arrow has stayed in good shape, thanks to being preserved in a gigantic freezer, which is precisely the nature of a perennial snow bank.

Such finds can also answer questions about prehistoric weaponry.

More treasures in the snow

When researchers find things in snow patches, one of their tasks is to estimate how many times the objects have melted out and later been recovered in snow.

Objects that have been frozen a long time are generally in better shape than those that have been exposed periodically.

“We don’t think this particular arrow has melted out of the ice many times. Maybe only the once since it was shot,” says Callanan.

That is an issue he and his colleagues are exploring.

“If it turns out that 2011 is the first time it emerged from the snow and ice, that says a lot about climate change and the melting of snow patches that we’re experiencing now,” says the researcher.

While global warming and climate change are generally not seen as positive developments, one plus of warmer temperatures is that more archaeological treasures in the mountains are coming to light.

“A lot more finds will be made in coming years as the temperatures rise and snow patches continue to melt,” says Callanan.

----------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling