Archaeologists' most exciting finds:

Investigating graves from Europe's first oil adventure

“The absolute coolest thing I've ever been a part of,” says the archaeologist.

Lise Loktu has served as an archaeologist for the Governor of Svalbard.

She participated in excavations of individuals involved in Europe's first oil adventure.

“This is the absolute coolest thing I’ve been a part of during my archaeological career,” she says.

From parasols to corset boning

People from near and far flocked to Svalbard in the 1600s and 1700s to take part in whaling.

Whale blubber was incredibly valuable, and Europe constantly demanded more.

“The whaling industry lasted for 200 years, from the 17th to 18th centuries,” says Loktu.

The blubber could be rendered into oil, fish oil, and soap. The oil was used for lighting, fabric preparation, and as a blending agent for dyes.

The bones were used for making parasols and corset stays for fashionable women.

Scurvy and drowning

The hunt for these large animals was dangerous.

Many whalers died during the hunting season.

“This led to the creation of large grave sites with unique burial traditions for those involved in the industry,” Lotku says.

Around 800 whaler graves from that time have been registered on Svalbard.

“Many also died of scurvy, a deadly disease caused by a prolonged lack of vitamin C, which was common among sailors and whalers,” she says.

The ships heading north carried small rowboats with a crew of six men in each. These were used for whaling, according to the Svalbard Museum.

When a whale was spotted, the goal was to hit it with a harpoon. The harpoon was attached to long lines that needed to run freely. If the lines got caught on the boat, the crew risked being dragged under the icy water.

Several rowboats would join in and secure their harpoons to the whale. Blood from the wounds would flow into the sea, and when the whale was exhausted, they could get closer and kill it with lances.

Back on land, the strips of blubber were cut off and then boiled to fill barrels with oil.

Hair, skin, and innards

Today, Loktu works as a researcher at the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research.

She studies the lives and health conditions of whalers and the impact of climate change on archaeology in Svalbard.

“Nowhere else are there so many well-preserved graves representing parts of the European population from this period,” she says.

The graves have been exceptionally well-preservation in the cold climate and permafrost.

“The buried individuals still have their skeletons, and remains of hair, skin, and innards have been found,” she says.

The clothing of the poor

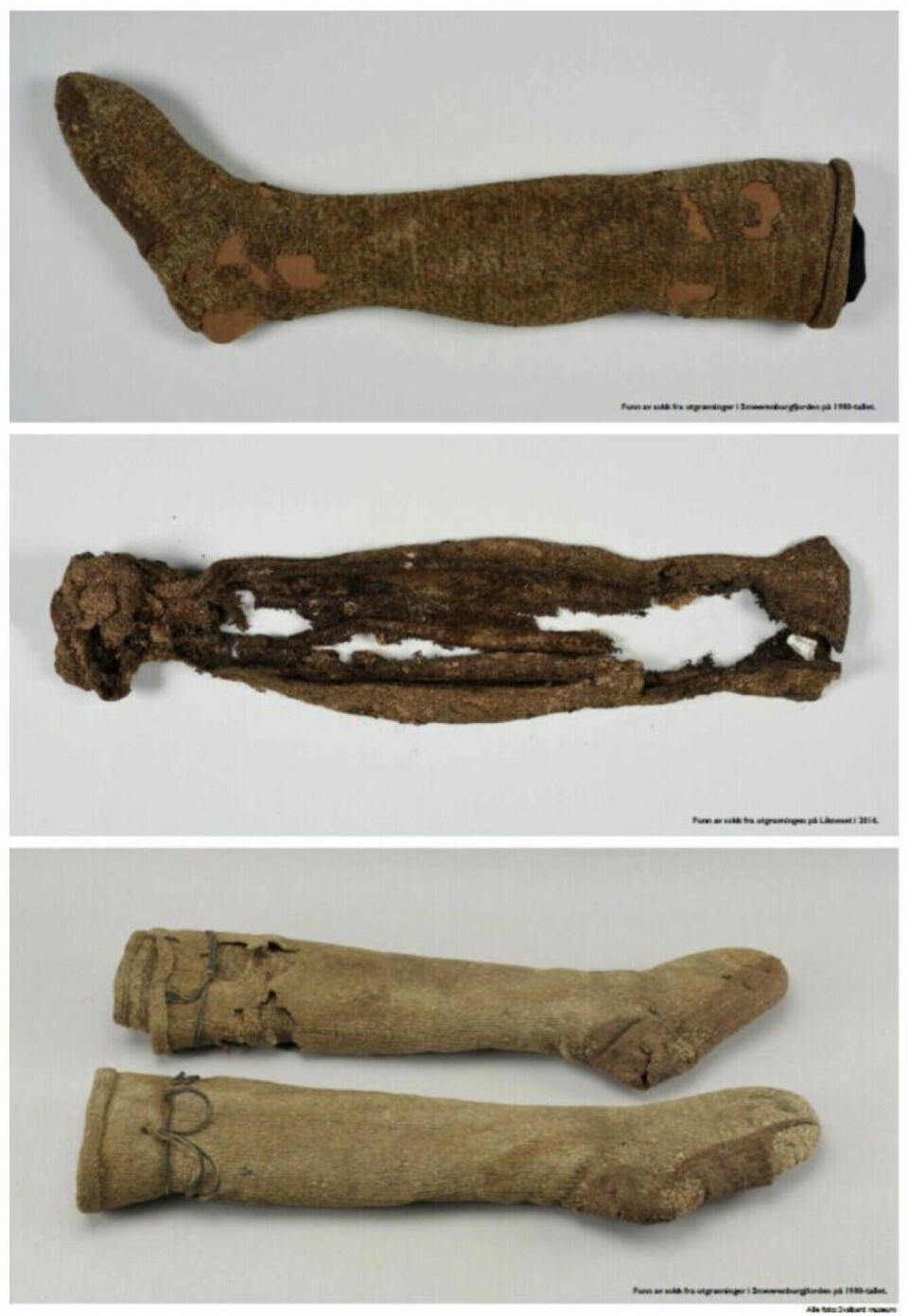

Archaeologists have also found well-preserved coffins, equipment, and clothing.

“In museums around Europe, textiles from the upper class are often represented. There has been little knowledge about the clothing and equipment of ordinary people,” says Loktu.

The whaler graves have given us valuable new insights.

“We see that they repaired and used their clothes for a long time. These were poor people,” she says.

It also appears that the clothes worn in Svalbard were not specially adapted for whaling.

“They simply used regular winter clothes from their homeland,” she says.

The knowledge of the past is disappearing

“In Norway, graves made after 1537 have no formal protection. As a result, knowledge about the people who lived in the following centuries is gradually lost,” she says.

On Svalbard, however, these graves are protected.

“The skeletons are therefore a crucial source of information about the European population of that time,” she says.

Archaeologists can study people's diet, lifestyle diseases, wear and tear, and other health issues.

The skeletal analyses, along with the various clothing items, can also reveal different social groups, statuses, or professions among the whalers.

“Wear and tear on the skeletons suggest that some had very physically demanding jobs. Others were rowers or harpooners. The society was highly stratified,” she says.

Analysing DNA

Loktu explains that graves are crucial sources for archaeologists, providing insights into past societies and human lives.

“However, there are many ethical aspects to consider in this work, such as whether the individuals can be identified and if they have known descendants,” she says.

Archaeologists have used DNA and isotope analyses to determine where the whalers came from, what food they ate, and other health factors.

Isotopes from our diet accumulate in the skeleton and can indicate where people grew up and if they moved later in life.

“DNA can give us information about the genetic origins of the whalers,” she says.

The analyses show that people from the graves came from several different nations, even if they worked on, for example, a Dutch ship.

“But the graves are gradually being washed into the sea by erosion, so it's about saving knowledge that’s disappearing,” she says.

The research project will continue for several years, and Loktu hopes to share exciting results in the future.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no