Why are so many more people developing asthma and allergies now compared to before?

The number of Norwegians with asthma and allergies has increased dramatically since the mid-1900s.

Not everyone dreams of spring.

For around 20 per cent of us, nature's annual awakening comes with side effects:

Runny nose, sneezing, and itchy eyes.

Some are so troubled by pollen allergies that they have to stay indoors when the pollen count is at its highest.

The problem is affecting more and more people. The percentage of those with allergies has increased dramatically from around 1 per cent at the beginning of the 20th century to 15-20 per cent today, according to figures from the World Health Organization (WHO).

Among young people in Europe today, there are twice as many who are allergic to pollen as there were 30 years ago.

But what happens when a beautiful spring day ends in outbursts of snot and tears?

And why you?

Wrong information

The first question has a fairly straightforward, if not entirely simple, answer:

Your symptoms are caused by your immune system.

Most viewed

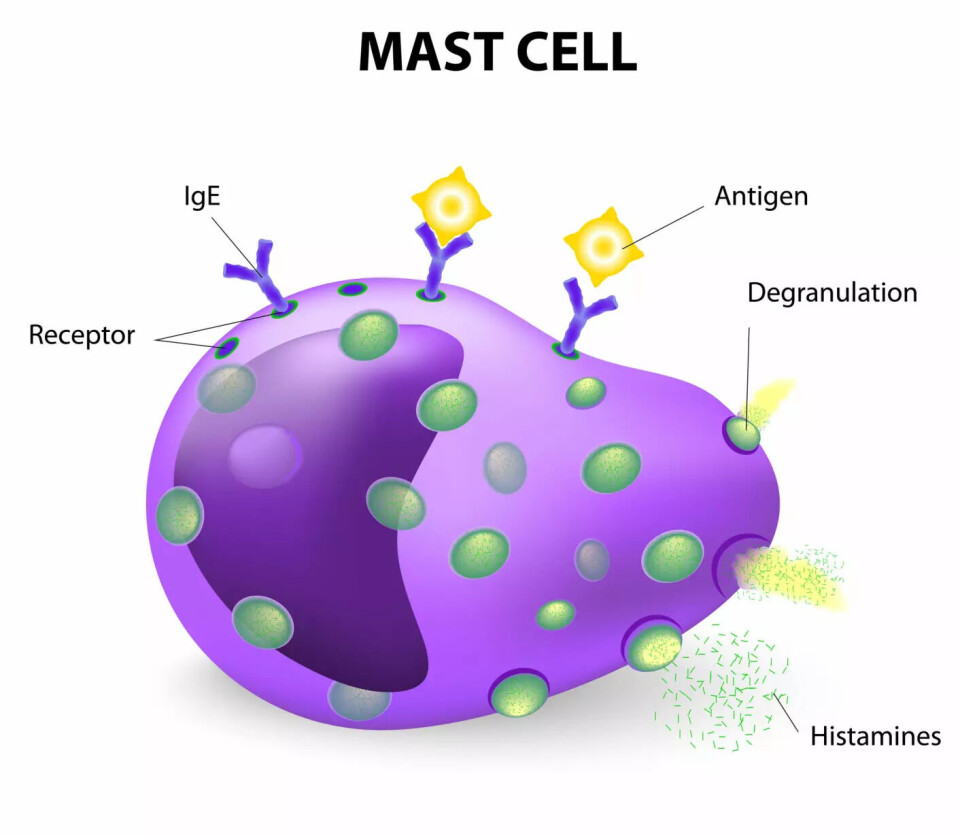

In your skin and mucous membranes, there are many cells called mast cells. Their job is to recognise dangerous intruders and then initiate reactions to eliminate the threat, for example, by sneezing it out or washing it away with tears.

The problem for those with allergies is that the mast cells have received incorrect information about what is dangerous and what is not. Instead of looking for viruses, bacteria, and parasites, they are on the lookout for harmless things like pollen or substances from a cat's skin.

This also explains why it is specifically pollen and pet dander we react to.

Unlike other irritating substances – such as road dust – pollen and animal dander consist of proteins. The exteriors of truly dangerous invaders, like viruses and bacteria, are also made of proteins. Therefore, the immune system is mainly concerned with recognising proteins.

And when such an allergen is recognised by the mast cells in the skin or mucous membranes, they initiate the reactions we experience as allergic symptoms.

The question is, of course, why the mast cells have received incorrect information.

Life in the West

Now, it’s becoming more uncertain.

Even though allergies are very common, there is still much we don't know about their underlying causes. However, our theories are more reliable today than before, says Martin Sørensen, senior physician at the University Hospital in North-Norway.

“We know that genetics play a significant role. Allergies often run in families,” he tells sciencenorway.no.

But genetics alone do not explain everything, such as the dramatic increase in the prevalence of allergies.

“We now see that the bacteria in our gut, on our skin, and in our mucous membranes are crucial for the development of the immune system, especially in young children,” says Sørensen.

“And our Western lifestyle over the past 40 to 50 years has led to a decline in these beneficial bacteria.”

This, Sørensen believes, might be a key factor in why our immune systems are maturing improperly, leading to a surge in various immune-related conditions like allergies, autoimmune diseases, and even obesity.

Antibiotics and plastic playgrounds

So, what is it about the Western lifestyle that disrupts the development of the immune system?

Sørensen suspects that the use of antibiotics may play a role.

“Antibiotics can destroy the natural bacterial flora in children. We’ve seen an increase in allergies and autoimmune diseases since we started using antibiotics,” he says.

Animal studies have directly shown that antibiotics can elevate the risk of developing allergies.

Additionally, many of us live surrounded by glass and concrete, and our children play in daycare centres where the ground is often covered with plastic, Sørensen adds.

“We sanitise and sterilise everything. But in societies where it’s not as clean, there’s significantly less allergy,” he says.

“For instance, a Finnish study involved spreading forest floor material in urban daycare centres, and they observed a reduction in allergies. Children putting soil in their mouths might seem dirty and risky, but it’s actually a way for them to build their immune systems.”

Read more about the Finnish study here.

This gives us clues about how we might prevent future generations of children from developing allergies to pollen and other harmless substances in our environment.

But what about us adults? Is is too late for us?

Faecal transplant

“This is a heavily researched area right now, but we don't have definitive answers yet,” says Sørensen.

He explains that some experiments involve transplanting faecal matter from a healthy donor into the intestines of individuals with allergies.

“But it’s not easy to establish a new gut flora,” he notes.

There is also a significant gap in understanding regarding which bacteria are necessary and precisely how this gut flora influences the immune system.

However, we do know that certain factors can affect allergies in adults.

There are numerous examples of people who either develop new or worsening allergies in adulthood or who outgrow allergies they previously had.

Hormones and Covid-19

Sørensen believes these changes might be due to factors affecting the immune system.

There is reason to believe that hormones can influence the body's defense system. Many women notice that allergies may appear or disappear during pregnancy.

Major life stresses can also have an impact.

“This could include undergoing major surgery, experiencing a serious infection like pneumonia, or even enduring severe psychological stress. We know that such events can influence the immune system,” Sørensen explains.

He has previously told forskning.no that he has personally observed a significant increase in patients experiencing either worsening or newly developed allergies following the Covid-19 pandemic.

More research is needed

At present, this observation is based on Sørensen’s personal experience. However, there are studies suggesting that certain types of infections are linked to an increased risk of developing allergies.

Recently, a study using data from South Korea, Japan, and the UK reported a similar increase in allergies following Covid-19 infection.

The study found that the risk of developing allergies post-infection rose in correlation with the severity of the illness. It also indicated that vaccinated individuals did not experience the same increased risk as those who were unvaccinated.

However, it is crucial to understand that these findings are not definitive.

This type of study cannot conclusively determine whether the Covid-19 infection itself led to an increase in allergies. This study is also the first of its kind. More research is needed before we have any firm conclusions.

Nevertheless, it is clear that immune reactions, such as those causing allergies, can evolve over time.

“Many people outgrow their allergies. It’s interesting that an overactive immune response can be temporary,” says Sørensen.

Allergen immunotherapy

There is ongoing research into how the immune system interacts with its environment and the rest of the body. However, we still don’t have enough knowledge to develop a cure for allergies.

Currently, the closest approach we have is what is commonly referred to as allergy immunotherapy, or allergy shots.

In reality, these are a form of exposure therapy designed to make the immune system less reactive to a specific allergen, such as birch pollen.

The treatment involves taking a tablet containing a small dose of birch pollen daily over an extended period – often several years. Over time, the immune system becomes less sensitive to the allergen. However, the effectiveness and duration of the results can vary.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik