Is organic food healthier than other foods?

There seem to be some differences between organically and conventionally grown foods, but the health effects are uncertain.

Yes, there are some differences between organically grown food and food produced using conventional methods, said Siv Kjølsrud Bøhn at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences' (NMBU) conference on nutrition and sustainability.

“Most summary articles that address this issue seem to agree that there is some difference,” said Kjølsrud Bøhn, an associate professor of nutrition and biomedicine at NMBU, in her lecture.

Nevertheless, there is no clear evidence that these differences have any bearing on health. There has been relatively little research on this, she said.

More vitamins and minerals, less protein

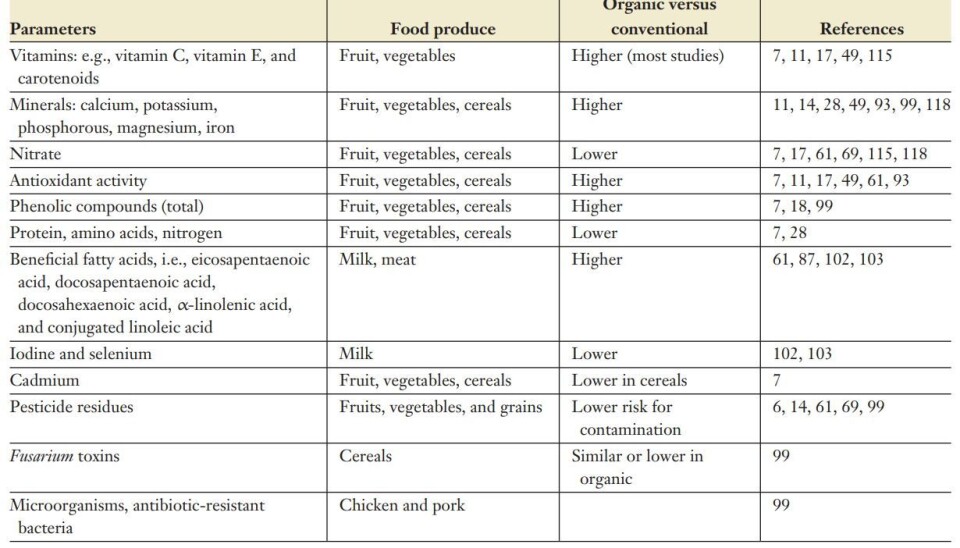

Kjølsrud Bøhn described a summary study done by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health in 2017. Here, the researchers looked at studies that compared organically and conventionally produced food.

“They saw that the levels of vitamin C were much higher in the organically produced foods. They found that there were some minerals that were also higher in fruit, vegetables and grains for the organically produced foods,” Kjølsrud Bøhn said.

The summary also reports that there was evidence of more antioxidant activity and what are called phenolic compounds in the organic food. These are assumed to be positive substances in plant-based foods.

Not all research points in the same direction. A Danish study from 2010 concluded there was no difference in mineral and antioxidant content between organically and conventionally grown carrots, potatoes, and onions.

That study also found lower levels of protein in the organically grown food. This may be related to differences in fertilization, Kjølsrud Bøhn said. Artificial fertilizers are not used in organic farming.

Several differences

When it came to milk and meat, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health summary reported that organic products contain a higher level of beneficial fatty acids. Additionally, they found there is somewhat less iodine and selenium in organic milk.

Organic plant products had lower levels of cadmium, which is a heavy metal. Organically grown grain products also contained less of a type of fungi-related toxin than their conventional counterparts.

Not surprisingly, there were lower levels of pesticide residues, or pesticides, in fruits, vegetables and grains grown organically.

These lower pesticide residues are the most convincing difference between organic and conventional foods, Kjølsrud Bøhn said.

“There are consistent reports that pesticide levels that are ingested in food decrease with an organic diet. This is true both in terms of the amounts found in the food itself and in the amounts found in urine samples in humans,” the researcher said.

Pesticides in food in Norway

Are there pesticides in food sold in Norway? Much of the food that Norwegians eat is imported.

Kjølsrud Bøhn has participated in an experiment where researchers measured pesticide residues in urine. This was in connection with a student course at the University of Oslo, where Kjølsrud Bøhn had previously worked. The results have not been published yet.

Participants ate plant food that had been grown organically for a week and plant food that had been produced conventionally for a week.

“We found a lower level of several of the pesticide residues as soon as after just one week of shifting to organic food. The results suggest that people in Norway are also exposed to pesticides on our food,” she said.

There are established limits for allowable amounts of pesticide residues in food. The Norwegian Food Safety Authority ensures that the rules are followed. In general, the levels in foods consumed in Norway are well below the limit values, according to Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

Do the differences have an impact on health?

In sum, there appear to be slightly higher levels of some substances in organic food, and less of some unwanted substances. But it remains unclear whether these differences have an impact on health.

“In fact, there has been very little research on this,” Kjølsrud Bøhn said.

In a summary study conducted by the Danish International Centre for Research in Organic Food Systems (ICROFS) in 2016, researchers found no evidence that organic food has health benefits.

“Even though there are healthy substances in organic foods, it’s difficult to document health effects, because people smoke, drink and exercise. As a result, it’s very difficult to investigate what is due to what,” said Lizzie Melby Jespersen, who worked on the report.

Investigated connections to cancer risks

Kjølsrud Bøhn described a newer study done in the field that was published in 2020 in the journal Nutrients. Here, the researchers found some results related to cancer, obesity, heart disease, pregnancy-related health, congenital malformations in boys and biomarkers, she said.

In two large population studies called NutriNet-Santé and the Million Women Study, the researchers looked at whether eating organic food has a bearing on cancer risks.

In one study, which was French, researchers found that people who often ate organic food had a lower risk of cancer. This was especially true for postmenopausal breast cancer and for lymphoma.

In the second study, which was British, no association was found with cancer risk, except for a possible lower probability of a type of lymphoma called non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

The French population survey also found a lower risk of obesity and metabolic syndrome in those who often ate organic food.

Metabolic syndrome is a collection of disorders in how the body metabolizes nutrients, according to the Norsk Helseinformatikk AS Norwegian website.

One study showed a possible lower risk of heart disease, but the quality of this study was not very good,” Kjølsrud Bøhn said.

During pregnancy

Some studies have also been conducted to see if there are benefits to eating organic food during pregnancy.

The Norwegian Institute of Public Health has found a link between organic food and a reduced risk of boys having hypospadias, a malformation of the urethra. The study was published in Environmental Health Perspectives.

Another study based on the Norwegian Institute of Public Health's Mother, Father and Child Cohort Study showed a lower risk of preeclampsia in pregnant women who often ate organic food.

More research is needed

Kjølsrud Bøhn summed up the situation by saying that research is beginning to emerge that may indicate there are some positive health effects from eating organic food.

“But overall, there are very few studies, so we need much more research to be sure,” she said.

One challenge in finding the answers to this question is that people who eat organic foods may have other shared characteristics that affect health.

“It can make it difficult to interpret results because people who eat organic food also often are in better health. They may be less overweight, for example,” she said.

Organic or not, eating a variety of healthy foods is good for you.

“I want to emphasize that it has been very well documented that a healthy diet protects against the risk of diseases, regardless of whether the food is organic or not,” Kjølsrud Bøhn said.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

References:

Anne Lise Brantsæter, et al. “Organic Food in the Diet: Exposure and Health Implications,” Annual Review of Public Health, March 2017.

Vanessa Vigar, et al. “A Systematic Review of Organic Versus Conventional Food Consumption: Is There a Measurable Benefit on Human Health?,” Nutrients, 2020.

Hanne Torjusen, et al. “Reduced risk of pre-eclampsia with organic vegetable consumption: results from the prospective Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study,” BMJ Open, September 2014.

Julia Baudry, Karen E. Assmann & Mathilde Touvier: “Association of Frequency of Organic Food Consumption With Cancer Risk - Findings From the NutriNet-Santé Prospective Cohort Study,” JAMA Internal Medicine, December 2018.

K. E. Bradbury, et al. “Organic food consumption and the incidence of cancer in a large prospective study of women in the United Kingdom,” British Journal of Cancer, 27 March 2014.