Back to the unnatural

Idyllic Norwegian nature isn’t completely natural. Much of it has been formed through centuries of forestry, farming and animal husbandry. Do we want to return to our scenic but impacted landscapes, or should we let the woods return?

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

“About a sixth of the country is on the verge of undergoing regrowth,” says Anders Bryn, a researcher at the Norwegian Forestry and Landscape Institute at Ås.

He has monitored and charted this development and the traditional interplay between Norwegian nature and Norwegian culture.

Scenic deforestation

Large portions of our country have been altered through human endeavours. Over half of Norway would have more forest if we and our livestock gave it a chance. Sheep, cattle, goats and horses have browsed in the mountains and kept trees from growing. The cutting of trees for fuel, lumber and shipbuilding opened up the heaths and uplands of South Norway.

“Many people think they are hiking through pristine nature but they’re actually in deforested landscapes,” says Bryn.

“They don’t realise the landscape they see is the result of the construction of houses, fences, iron smelting, evaporating water for sea salt, cheese-making, gathering forage and other activities people have carried out in the outfields and wilderness to make a living.”

He adds that people from the Netherlands who were interviewed by the Norwegian Centre for Rural Research admired the nostalgic Nordic idyllic countryside, as if it were an outdoor museum.

"When they heard the landscape is still being formed by on-going agriculture, they couldn’t believe it.”

Regrowth is not wholly negative

But when farms close down the forest regains its territory. Without livestock to keep the seedlings and scrub growth back, thickets grow where old mountain farms and pastures once ruled.

Is this an undesirable development? Should we try to bolster the strongholds of cultivated land against the persistent onslaught of nature? Go back to the unnatural? Or should we let the woods win?

“The regrowth isn’t wholly negative,” says Bryn.

He and his colleagues have discussed the issue for decades in a number of articles. Bryn suggests some arguments in favour of regrowth:

“The forest traps carbon dioxide. The forest acts as a buffer against floods. Tourists from Germany and other densely populated regions have little forest in their home countries. For decades Central Europeans have heard about the forests being in jeopardy and needing better care. They like to see forest.”

What tourists want

On the other hand: the tourists are dissatisfied when they can’t see the forests for the trees. The woods mustn’t block Norway’s often spectacular panoramic views.

“Most large studies show tourists are happiest when the landscape and scenery are varied ― woods, lakes and open spaces. Classic rural landscapes in Norway have just that.”

Bryn and his colleagues have studied where tourists roam and their work will be published in a forthcoming article. Together with the Institute of Transport Economics, they’ve studied the routes taken by 4,500 tourist coaches and established an overview of elements including hotels, mountain lodges, cabins and national tourist roads.

The result is a map showing popular tourist areas and places where the forest is recapturing territory. Do these spots overlap?

Overgrowth in the mountains and by the fjords

“We discovered reforestation in many tourist areas, but not all up and down the country.”

The researcher says that traditional tourist hotspots like Høvringen, Beitostølen, Venabygdsfjellet and Vaset in the mountains of South Norway as well as several destinations in West Norway, in Lofoten, Vesterålen and the Helgeland coast are becoming overgrown,” he says.

“And it isn’t stopping there. The overgrowth will continue at full speed along the coast and in the mountains. As many as 60,000 holiday cabins could lose their views in the coming years.”

The tourist and travel trade has helped finance this research but the researchers have had a wider perspective than tourism.

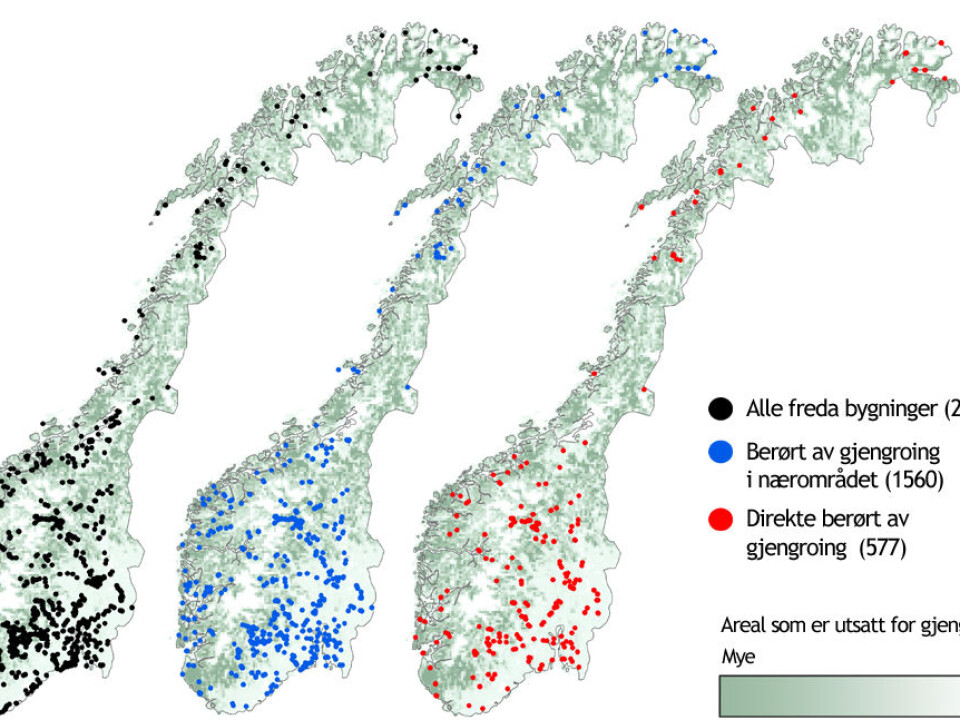

Harming cultural relics and diversity

“The overgrowth can destroy cultural relics. Pitfalls [dug by hunter-gatherers] that used to lie in open mountain terrain are being destroyed by tree roots and decay in the forest. Listed buildings can rot when the forest closes in around them,” he says.

New forest also hides the old landscapes which were the historical frameworks around such historical and cultural relics.

But freely growing woods must at least be good for biodiversity? Isn’t that why we establish nature reserves?

“It’s true that old virgin forest hosts a rich biodiversity. But the woods need several hundred years of undisturbed growth to mature into virgin forest,” explains Bryn.

First desolation, then diversity

A cultivated landscape provides a basis for many species that otherwise wouldn’t survive in Norway. On the whole, pastures, cultivated forests and coastal heathlands provide more biodiversity than young forests do.

“Nearly a third of the threatened animal species on the so-called red list live in cultivated landscapes.”

These species will die out when the young birches take root in old fields and pastures, before tall spruces in turn strangle deciduous woods beneath their heavy shadows.

If the forest gets rooted in old culture man-made environments, biodiversity will also lose out in the short run. Rare species of wild plants, insects, birds etc. will disappear, as more common species and types of nature take over.

It will take a long, long time before the forest diversity can evolve among rotting trunks and tall trees.

“The best thing for biodiversity would be to maintain variation, with open cultivated landscapes and primal forests,” says the researcher.

Semi-natural reserves

In 2003 the book Norge 2015 – en reise verdt? [Norway 2015 ― worth the trip?] was published. It was written by Jonas Gahr Støre [now the Minister of Foreign Affairs] and others, and discussed future challenges facing tourism in Norway.

“One of the things it highlighted was that many tourists view Scandinavia and Norway as the last wilderness of Europe,” says Bryn.

“But we’re objecting to that. We think it’s more relevant to call Norway a semi-natural region, because we now know how strongly culture has impacted Norwegian nature.

“The challenge isn’t in the preservation of Norwegian nature, but in the preservation of the interplay between nature and valuable un-nature, semi-affected nature – in other words culture,” he concludes.

Translated by: Glenn Ostling