Arctic agriculture needs new crops

Countries in the far north need to cultivate new varieties of crops if they hope to main local food production.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

As anyone who works in plant cultivation and experimentation whether they think new plant cultivars are needed for northern agriculture, and nine out of ten will say yes.

Insufficient harvests

“We have targeted people who work with refining and testing new crop species as well as authorities and farmers' groups,” says Svein Ø. Solberg, a senior researcher at the Nordic Genetic Resource Center, NordGen.

He has teamed up with agricultural researchers from Greenland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands as well as Norway to conduct a survey of opinions in the Nordic countries about the need for new crops.

Solberg presented preliminary results in Lillehammer recently at the Conference on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture in a Changing Climate. But climate change is not the only reason for developing new strains and hybrids.

“We're talking about varieties that are better suited to a hotter climate, because of global warming. But we're also talking about the varieties we have today, which just aren't good enough to maintain agricultural production and strong harvests under the present climate conditions,” he says.

Valid results

The study also asked participants to suggest good plant varieties and say which they think are most suited to northern latitudes. These could include crops ranging from grasses and barley to berries and vegetables.

But how much can we trust these answers, when the people who were asked about the need for new crop varieties are the same individuals whose job it is to develop them? Solberg agrees that the method may not be perfect, but says he thinks the responses are valid.

It's true "if you ask people who cultivate new types about the need for new types you can count on them being supportive of their own line of work,” he said. “But farmers, government authorities, organisations, chefs and others who work with local products are all saying the same thing.”

“Botanists were actually more hesitant than the average [of those surveyed], while farming organisations were very clear about the need for new varieties,” he said.

Moving crops north is no simple solution

Solberg rejects the suggestion that humankind can simply plant varieties that have been used further to the south to keep pace with climate change.

“That is one way of thinking about it, moving crops northwards. But you have to consider the hours of daytime, especially for perennials such as grasses and clovers,” he says.

Day lengths fluctuate more at higher latitudes between summer and winter than crops from more southerly climes are adapted to, which means that plants' timing may be off. If you take plant species from south Norway and move them to the high north, they will continue to grow as winter hits and they die by spring.

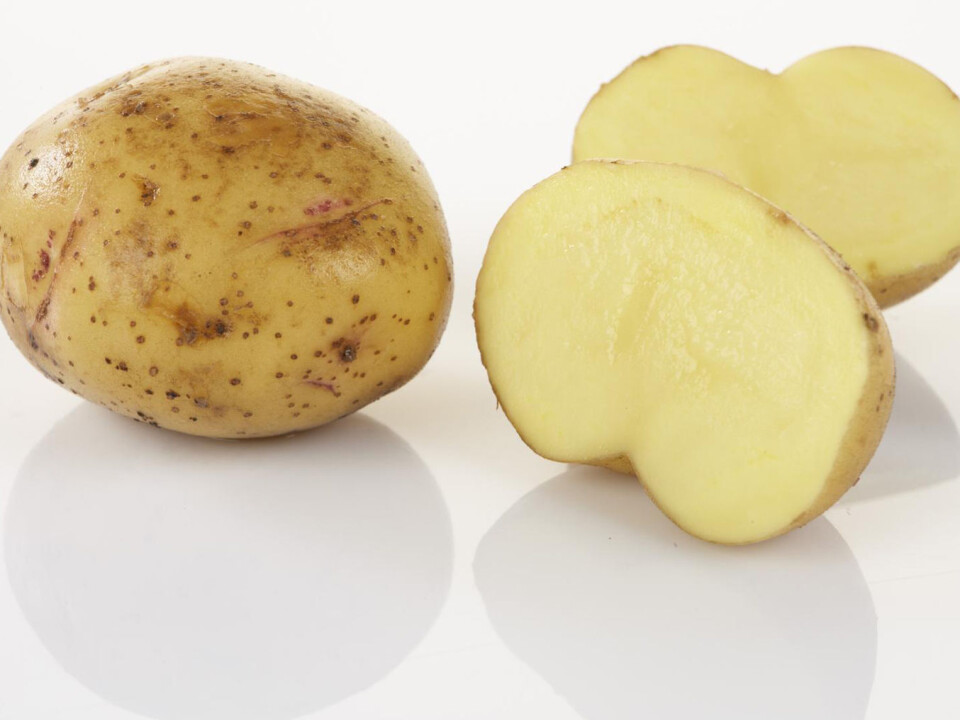

But Solberg says it is possible to move annual plant varieties to the north, such as potatoes and vegetables, because they do not have to survive the winter.

“We need to test different varieties and make plans for the ones that work out well,” says Svein Ø. Solberg.

He adds that experimental farming trials using alternative varieties could be better. Two out of three of the participants in the study are dissatisfied with the work being conducted today.

--------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling