Super salmon training starts early

Healthier, stronger, bigger: this is a goal for Norwegian farm-raised salmon—and Harald Takle is their personal trainer.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Takle, a Senior Scientist at the food research institute Nofima, is also an avid outdoorsman, but he doesn’t jump up salmon ladders, nor does he crawl around in sea cages. He oversees the salmon training in round tanks that are small versions of those used by the aquaculture industry.

“The current in the tank forces the fish to swim upstream,” says Takle. The tanks are in the fish gym at Nofima's research station, located in Sunndalsøra in Møre og Romsdal county, Norway.

Little athletes

Takle leads the researchers who are helping the fish farming industry to grow healthier, stronger and larger salmon. Fish are like people: exercise increases their disease resistance. A healthy and strong fish is a good fish. “Training improves the texture of the fillet,” says Takle.

Training begins early. Takle’s youngest clients weigh only 1.8 grams and measure 5 centimetres. “The newest results show that the well-trained fry ate more and grew faster. “They tolerated harder workouts as they grew,” he says.

Training for adulthood

When the salmon fry weigh 20 grams, they move to a larger tank. They are called parr and live in freshwater—salmon teenagers as it were—not yet ready for adult life in the salty ocean.

Wild parr swim in rivers, and the salmon parr in Nofima's research station swim in round tanks with strong currents. The parr stage is the easiest and most important time to train salmon.

Research results have to translate into commercial benefit. The closed system makes it easier to give the parr a controlled countercurrent to train in.

The parr soon move out into sea cages. Now called smolts, they need all the strength they can muster in the briny reality outside the tanks.

Researching the training curve

“It's a tough transition for smolts,” says Takle. “They’re transported by car and boat, and pumped out from freshwater tanks into the cages in the fjord. There they encounter a new environment, other bacteria and viruses, extreme weather and strong currents. The smolts have to be in good physical shape to withstand all the stress.”

How do smolts hit their peak form? Takle and his colleagues have been researching smolts’ training levels for several years. “The key is to provide the right amount of training. Overtraining doesn’t give their muscles time to rest and grow. It’s the same as in humans,” Takle says.

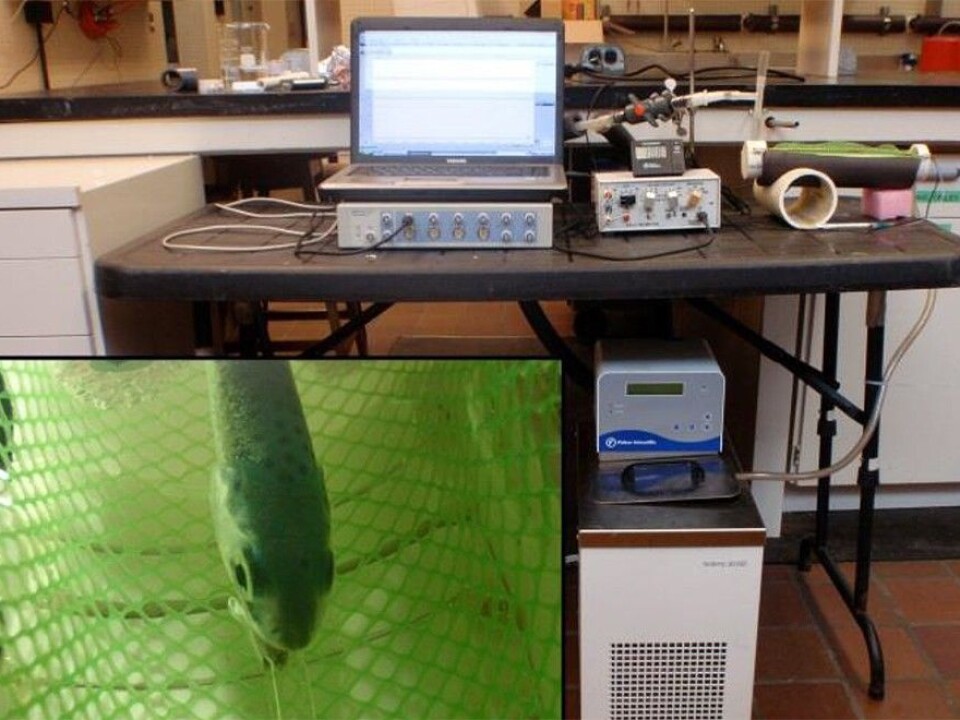

To find out how much exercise a smolt can actually tolerate, researchers must test their limits. The test starts with a fairly weak countercurrent in a specially made glass tube. Then the trainer slowly and precisely increases the speed, up to around 5 km/h. The smolts that give up end up in a net behind the tube.

“A few smolts were able to swim at full steam in the highest countercurrent for the equivalent of three kilometres,” says Takle.

Fish-EKG

Water that is too warm can also be a stressor in the cages. Fish metabolism increases in the heat of summer, and the warm seawater is also less able to hold dissolved oxygen, which can lead to oxygen deficiency for farm-raised salmon.

A salmon’s fitness level partly determines how little oxygen they can get by on. “The better the heart pumps blood, the more oxygen reaches the muscles and other body parts, so it’s important to measure oxygen uptake,” says Takle.

With the fish in a closed tank, researchers measure how fast the oxygen level in the water drops. They record maximum oxygen uptake during strenuous exercise and rest. The difference between these uptakes indicates what fish can tolerate.

Researchers also measure heart rate increases in warmer water with a kind of fish-EKG. “Water that is too warm results in cardiac arrhythmia—the heart stops beating smoothly and strongly,” says Takle.

He says researchers also use other methods to find out how fish react to training, including evisceration. “Several fish diseases can affect the heart, so we study it thoroughly, including measuring the shape of the heart. An athletic fish has a pyramid-shaped heart.”

“In short, we can say that a trained fish is a leaner, bigger, healthier and stronger fish,” says Takle. “And our latest results show that the earlier the training starts, the better it works.”

----------------------------

Read this article in Norwegian at forskning.no

Translated by: Ingrid P. Nuse