Creatures from the deep and cold Atlantic sea

Check out what swims around a thousand metres down off Greenland.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

The BBC and other documentary producers have created an industry out of presenting the mysteries of the ocean depths. Thousands of metres beneath the waves are species we’ve never seen, heard of or imagined could exist.

But you needn’t probe the great ocean rifts and troughs to reach exotic and strange creatures. Scientists on board the research ship “G. O. Sars” never trawled deeper than a kilometre during our voyage from Greenland to Norway, but they come up with some fascinating catches.

From the surface down to 1,000 metres

The sea is divided into vertical zones.

The entire free mass of ocean water, everything above the seabed, is referred to as the pelagic layer. It’s divided into horizontal zones but the most important is the mesopelagic zone. This comprises the murky depths from around 200 metres to 1,000 metres.

The epipelagic zone stretches down from the surface to 200 metres.

These are the two zones the researchers on “G. O. Sars” are studying on this voyage.

The two zones contain krill, small fish and many other tiny morsels which are eaten by commercially important fish like herring and mackerel.

Mostly jellyfish

We are approaching the Irminger Sea, south of Iceland, but we are still west of the southern tip of Greenland. The clocks on board are still set at Norwegian time, GMT +1.

So when the deep-sea trawl net is lifted on deck it’s 11 PM. Yet the sun is shining and keeping the scientists and crew warm as they pull in the nets.

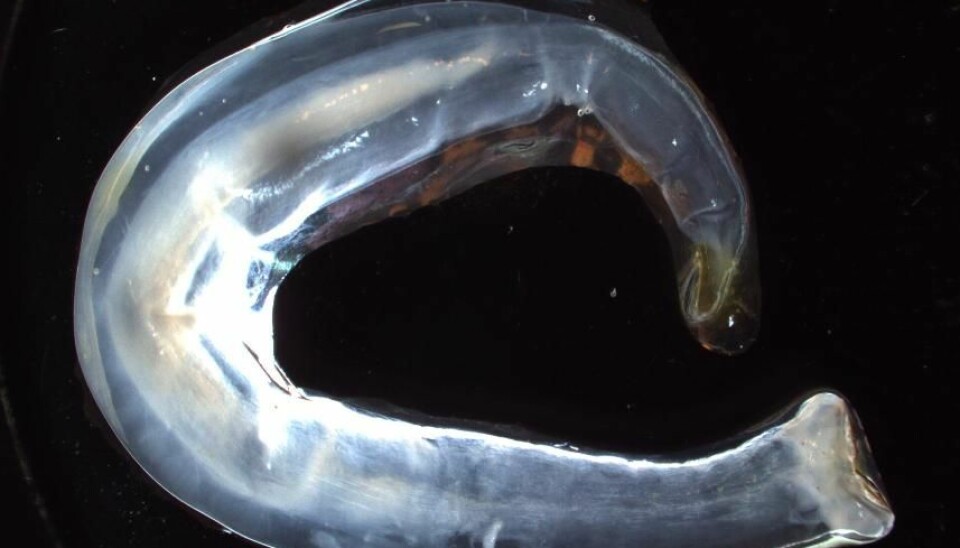

Jellyfish dominate the catch. The Institute of Marine Research’s jellyfish experts got off in Nuuk, so the scientists aren’t particularly enthusiastic about the wet, stinging clumps that flicker in the sunlight.

An hour or two passes from the time a trawl net is released until it is hauled on board again. This can be devastating for some the fragile creatures that are caught. The flow of water presses them against the net and one another.

So much that is brought up is damaged goods, but not everything.

Freezing catches for identification back in Bergen

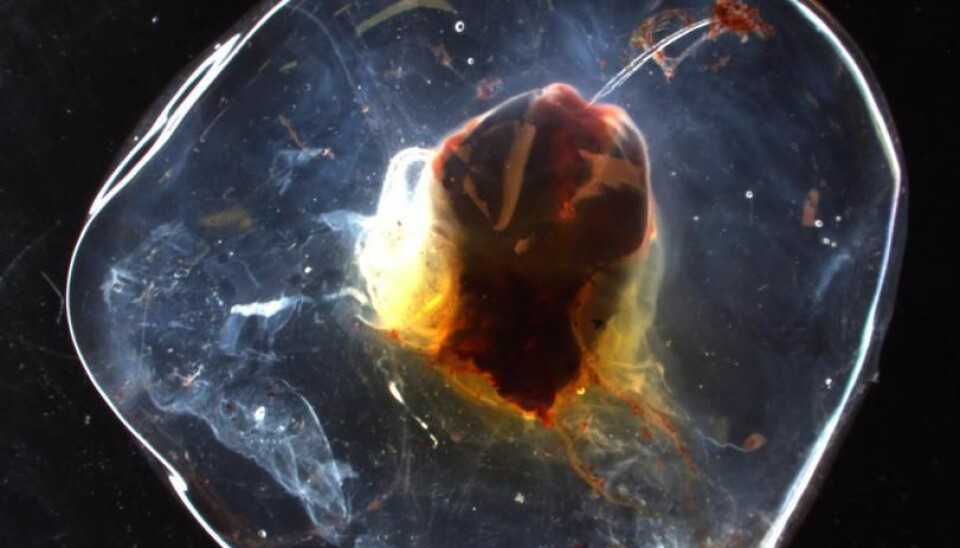

The scientists are not netting sea creatures in the mesopelagic zone for sport or for our next meal. The plan is to capture and chart some of the rich diversity of animal life down where the sun never shines.

Most of the scientists on the ship are more used to voyages in the Norwegian and Barents Seas. Few have worked in these Atlantic waters to the west and are sometimes surprised by what is hauled on deck.

Time is a factor when the catch is swung aboard.

Known and unknown species are registered, measured and weighed as quickly as possible. A little selection is frozen and brought back to Norway. Creatures that the scientists can’t identify can end up in special bags, market “indet” – indeterminable.

When frozen quickly at -80° C, the tissue and more importantly the creature’s DNA is preserved, so the researchers can examine them later in labs.

Translated by: Glenn Ostling