Cheap hamburger could be choice steaks

Little Norwegian beef ends up being served as steaks. With new feeding and butchering techniques the country’s cattle could provide more whole cuts and less minced or ground beef.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

More money could be earned by making better use of cattle. In Norway 70 percent of the animal carcass winds up as ground meat and 15 percent is sliced into various cuts of steaks, which of course achieve a better price per kilo.

Experiments by the food research institute Nofima in Ås demonstrate that various combinations of prime fodder and use of grazing lands yield tender and tasty cuts from more of cattle’s muscle tissue than have been commonly found in Norwegian meat markets.

New ways of slicing up the carcass can also yield more steaks.

Increasing the share of steaks

Whereas four or five muscles are used for whole cuts of meat in Norway and the rest is ground up for hamburgers, meatballs and the like, Americans use 40 percent of the carcass for various whole cuts of meat and run another 40 percent through the grinders.

Norwegians and Americans go their separate ways in other aspects of raising cattle. In the USA a larger share of beef is from castrated bulls and these have more fat spread through their muscle tissue. Labour at meat packing plants and butcher shops is also cheaper in the United States.

Leaner wages make it more profitable for American meat packers to cut out the smaller muscles which in Norway are tossed into the grinders with larger chunks of meat.

Nevertheless, Rune Rødbotten, a researcher at Nofima, thinks it’s possible to raise the share of steak cuts from Norwegian cattle by 10 to 20 percent.

He is midway through a four-year project looking into various grazing and feeding regimes that affect the tenderness of different muscles and the economic advantages of butchering the meat in new ways.

Many of the lesser known cuts of beef can be just as tasty as sirloin.

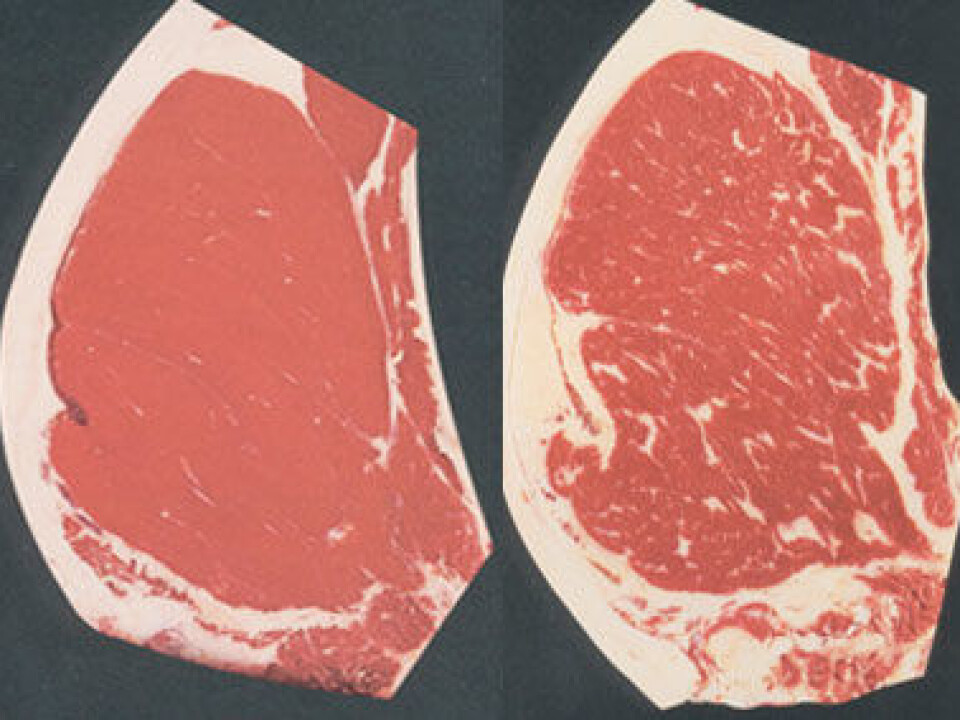

“There’s a correlation between marbling and tenderness, at least for some of the muscles. We’ve seen it in our tests, and in the USA they’ve based their quality assessments and pricing on this. In the USA they have much more intramuscular fat in their meat than we have here in Norway,” he says.

Intramuscular fat is the fat that is spread within a given muscle, not the bands surrounding it.

Fat policies

The leanness of Norwegian livestock is a result of conscious policy decisions.

The fat content in beef is classified on a scale from one to five, where one is the leanest. If the animal is fatter than class two, the farmer gets a lower price per kilo.

“This means that Norwegian farmers benefit from raising very lean livestock, both because they save money on fodder and because fatter animals would fetch a lower price per kilo. The difference can be around Euro 1.30 or more per kilo and with a 300 kilo carcass too much fat can mean a loss of Euro 400 per animal.”

Rødbotten says the policy in Denmark is just the opposite because fatter meat tastes better and is easier on the jaw. Danish farmers earn less per kilo if the meat is in fat class three or lower.

“The result is completely different meat. Steers grow faster and can be slaughtered when 12-13 months old, whereas Norwegian steers are often 20 months or more when they head to the slaughterhouse.”

Rødbotten attributes the difference to a combination of history and politics, both because Norway has a history as a poor country, and government policies aimed at giving farmers equal opportunities from the south to the arctic north, from lush valleys to barren hillsides.

“We have some farmers in sparsely populated regions, and we want to maintain agricultural production in the northern regions like in the rest of the country, even though the growth season for feed grains there is shorter.”

“The politics of agriculture is complicated, but we needn’t compel everyone to eat tough meat just because some of the regions have short cultivation seasons,” he says.

New muscles for steaks

Rødbotten also thinks we can utilise a greater portion of a carcass by butchering it in new ways. He mentions beef roast of knuckle, which is sold domestically and actually consists of four separate muscles tied together.

A very strong tendon runs between two main muscles, making the meat tough. But if you separate the muscles, removing the tendon, they are as tender as sirloin.

The top part of stewing beef, which consists of a large muscle running from the iliac crest and down the entire thigh of the animal, can also be used for steak. This is the culottes steak or top sirloin cap steak and is very popular for instance in Denmark.

Research by Rødbotten and colleagues shows that variations in feeds and grazing can increase tenderness.

For example an animal that grazes in unfertilised and overgrown outlying fields, which normally yields leaner livestock than the ones in fertilised pastures, can develop meat that is just as tender if they are given feed concentrates a couple of months before being slaughtered.

Farmers can kill two birds with one stone – they can utilise natural land that is cheaper to maintain, and the old outfields which are becoming overgrown all around the country can once again open up and be productive.

-------------------

Read this article in Norwegian at forskning.no