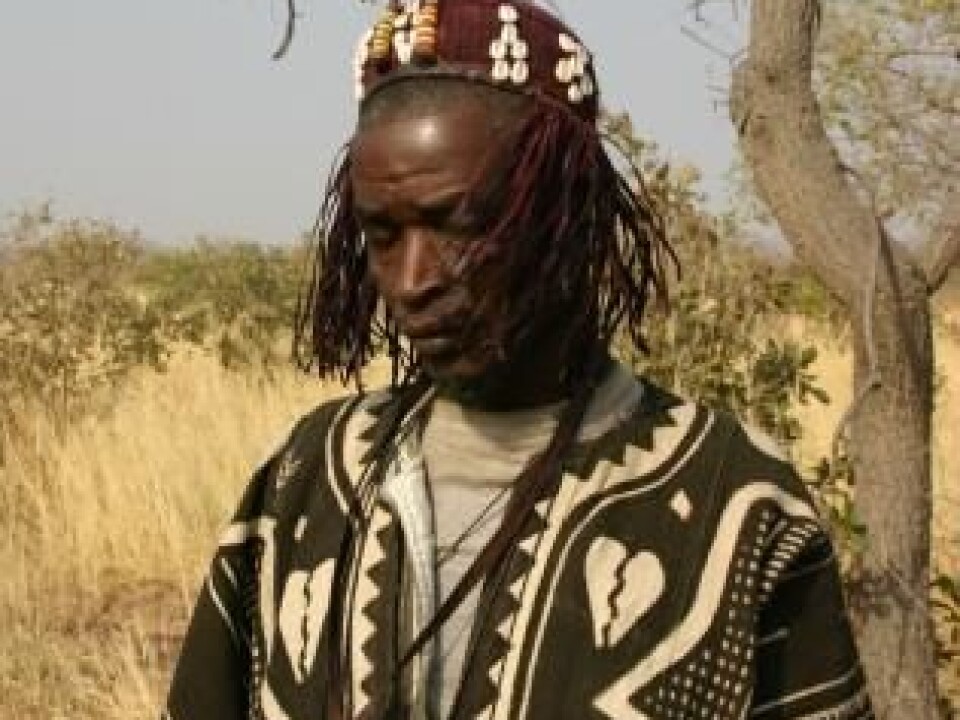

Researchers cooperate with ‘medicine men’

Pregnant women in Mali are dependent on medicine men and women, also called traditional practitioners (TPs) of folk medicine. Researchers are now collaborating with these healers to help improve their practice.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Approximately 75 percent of the population of West African countries rely on traditional plant medicines when they fall ill.

Healers, or TPs, play a key role in the primary health system of Mali’s 14 million inhabitants, including caring for women who are pregnant, giving birth or lactating.

Mali has only one doctor per 20,000 inhabitants. The risk of women dying during pregnancy or during the delivery of an infant is 100 times higher than in Norway.

What happens when TPs and healers have responsibility for treating pregnant women?

Master's degree students at the University of Oslo (UiO) and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health have joined the University of Bamako in interviewing 72 TPs or “medicine men” [although 64 percent of these healers were women] in Mali.

Treating 13 pregnancies per month

The researchers calculated that each TP or healer treated an average of 13 pregnant women per month. The ages of the TPs interviewed ranged from 34 to 90.

“Our study indicates that healers and TPs play an important part in the health care of pregnant women in Mali,” says Pharmacology Professor Hedvig Nordeng of UiO.

The researchers found that TPs in Mali know quite a bit about pregnancies and deliveries. They treat common maladies associated with pregnancy as well as diseases such as malaria.

Nausea and births

Many of the pregnant women who seek help from PTs have problems with morning sickness ― nausea. The TPs generally agree on which plants should be used to treat nausea and dermatitis among pregnant women, Nordeng says.

The researchers also observed that pregnant women with malaria were generally treated with fever-reducing plant medicines.

They catalogued more than 40 different medical plants that were used, and also found that traditional practitioners in Mali know very little about the mental problems that can plague pregnant women.

“We asked the healers specifically if they knew of any treatment for depression in connection with a pregnancy or birth,” says Nordeng.

This was a difficult subject. Most of the healers did not know about any medicinal plants that could be used for these kinds of ailments.

The researchers attribute this to the fact that it is taboo to talk about depression in many African cultures. The professor in pharmacology thinks mental health ought to get more attention in Mali.

Safer use of plants

Many TPs use the plant Cola cordifolia in difficult deliveries, because it is believed to help ease the birth.

“The healers often take special precautions when treating pregnant women. They said they refrain from using the strongest parts of certain plants. They also avoided the use of plant parts that taste bitter, because they thought this could lead to uterus contractions and a spontaneous abortion.”

Nordeng says that pharmacological studies have documented that many bitter plants contain high concentrations of alkaloids. Thus, there is scientific support for avoiding these compounds during pregnancy.

Now the researchers want to interview women in Mali about their attitudes and habits regarding plant medicines and pregnancies. The researchers hope to contribute to the safe use of medicinal plants during the birthing process, or afterwards, when women are breastfeeding.

The healers have main responsibility

Professor Berit Smestad Paulsen of UiO’s Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry was the first to initiate contact with Mali’s health officials and has played a key role in the project.

Paulsen says healers definitely have the main responsibility for health in countries like Mali.

“This is simply because there are no doctors available for most people.”

“The Mali authorities have created an official quality control system for healers, and are the first country in Africa to do so. Healers cannot be issued a certificate without demonstrating their ability to heal a certain number of people.”

Paulsen thinks this system could serve as a model for other African countries. She has received an EU research grant to continue collaboration with Mali health officials and will initiate similar projects in Uganda and South Africa.

Cheaper medicines

The National Institute of Public Health in Mali has opened a department of traditional medicine. One of the major priorities of the authorities is to bolster knowledge of folk medicine.

They want to ensure the public gets the best traditional medicines available.

“Traditional medicines are also cheaper than Western medicines,” Paulsen points out.

She has worked with her colleagues in Norway and Mali on laboratory studies to determine the chemical effects of the plants that are used.

Researchers and other partners from Mali will use this information to develop local medicinal products, which will then be made available in the country’s pharmacies.

Four students from Mali have earned their doctorates in pharmacology at the University of Oslo. They are now involved in the study of traditional medicinal plants in their home country.

-------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling