Arguing over what screens do to children is getting in the way of other important issues, researcher says

Growing up in the digital age is different from what children and young people have experienced in the past. What if some kids miss out on it?

Young people have never been more engaged with screens than they are now, and nobody knows the full consequences.

For many who grew up without digital technology, there are many questions and significant concerns:

Does screen time actually make kids smarter?

Or does it make them dumber?

Does it make them happy or unhappy?

When should parents intervene?

And do they really learn anything when they use tablets in school?

And most importantly, what dangers are young people exposed to by being online?

As important as light and heat

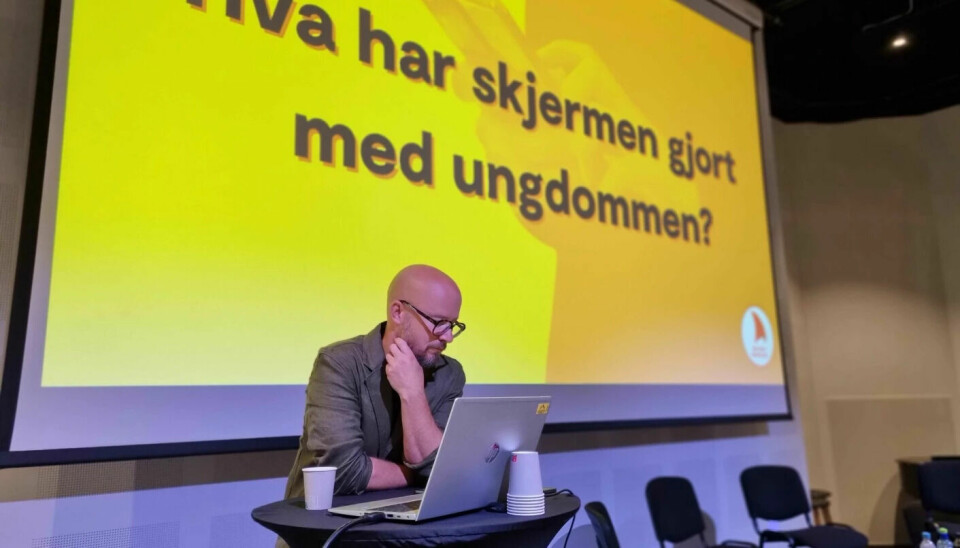

Christer Hyggen is a researcher at the Norwegian Social Research Institute (NOVA) and is particularly focused on children and young people growing up in a digital world.

“Over the past decade, mobile phones and tablets have more or less transformed the way we live our lives,” Hyggen said at a debate on youth and screens recently.

Our new lives are a direct consequence of technological development, but this is also a deliberate development, Hyggen said, pointing to the government position paper the Hurdal Platform from 2021.

“In this platform, high-speed internet access is equated with the right to electricity. That's because politicians have recognized that internet access is crucial for people to participate in society,” Hyggen said.

Strong divisions

Hyggen believes there's a great deal of polarization in the debate over digital media and youth.

“Some individuals are very fearful of what it does to children. And then there's the opposite position, where people who are positive to technology believe everything is fine,” he says.

“If these two polar opposites go unchallenged, it could hinder the effort to ensure that all children and young people have access and the competence to participate in the digital world they live in.”

Unrealistic concerns?

Are we exaggerating how the digital world affects our children then?

“Most children and young people transition easily between the digital and physical worlds,” Hyggen said to sciencenorway.no.

He and his colleague Idunn Seland have analysed Norwegian newspaper articles about the use of digital media by children and youths in the past few decades.

The researchers then looked at the screen habits of young people and the actual problems they experienced.

“What we saw was that the focus of people’s concerns didn’t actually match the reality. Most children and young people live their lives without cyberbullying and online abuse,” Hyggen said.

Young girls and social media

However, some groups do struggle.

“For example, there's agreement that growing up in a digital world can have negative consequences for certain groups, especially girls and their use of social media,” says Hyggen.

“There's a lot of research suggesting that excessive use can have adverse effects on their mental health,” he said.

But the research isn't entirely conclusive.

Earlier in August, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health published a study that shows a connection between negative experiences on social media and mental health among youth.

A second study from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) suggests that children and young people don't become depressed as a result of social media use.

So researchers aren't entirely sure how Snapchat, TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube affect youth.

Causes conflict in families

Hyggen calls it a digital upbringing.

“Digital upbringing changes both family life and school life. It changes more than just the way we organize ourselves, how we stay in touch, and how we communicate. Digital devices like mobile phones and tablets can also be a major source of conflict in the family, such as related to screen time,” he said

Hyggen says there’s an ongoing debate over the digitalization of schools.

“This fundamentally relates to a new battle for the student's attention,” Hyggen said.

Many parents are concerned about their children's learning outcomes. Are teachers capable of using digital tools, and are they aware of the challenges?

“What digitalization does is bind together school, family, and leisure time in a way we haven't seen before,” says Hyggen.

“These are important arenas for raising children, and the boundaries between them are becoming porous; they are merging,” he said.

Some are excluded

Hyggen is particularly concerned about children who are excluded from this digital upbringing. He calls it ‘digital deprivation’, meaning an inability to participate in the digital world.

“When everything social, in addition to schoolwork, moves over to digital media, it's especially important to be aware of this risk,” he says.

“We have to ensure that all children and young people have access to high-speed internet. In Norway, the physical infrastructure for this is very good. There are significantly greater challenges for the rest of Europe,” he said.

The fact that both social interactions and education take place digitally can contribute to widening the gaps between people, he explains.

“In larger families with limited income, there may be less access to mobile phones, PCs, and tablets. In these cases, children and parents might have to negotiate over who gets to use them,” Hyggen said.

“There might also be limitations on how much support children receive from parents due to the parents’ lack of digital expertise.”

No boundary between physical and digital

“It may be that we can no longer differentiate between the digital and the physical lives of young people,” Hyggen said.

For example, young people use gaming platforms like "Fortnite" to arrange basketball games in the schoolyard. Or they use YouTube when they discuss homework.

“At the same time, it seems that children and young people are aware that there's a distinction. They have different unwritten rules about how to behave digitally compared to how they behave in the schoolyard. They know they're being observed when they're online,” Hyggen said.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no